- Category

- War in Ukraine

AI-Powered Turret That Hunts Russian Missiles and Drones? Meet Sky Sentinel, Ukraine’s New Air Defense

Russia bombards Ukrainian cities with Shahed drones almost daily, terrorizing civilians from frontline cities like Kharkiv, Sumy, Dnipro, and Zaporizhzhia to distant hubs like Kyiv and Odesa. In response, Ukrainian engineers have built a homegrown defense system—Sky Sentinel—to fight back against the Russian aerial threat.

Russia has fired over 45,000 attack drones at Ukraine since February 24, 2022. Each one, loaded with explosives, costs anywhere from a few thousand to hundreds of thousands of dollars. Their targets: energy facilities, civilian infrastructure, and residential areas. On average, more than 100 Russian drones have torn through Ukrainian skies every single day, an intensity of drone warfare unseen in modern history.

To hold the line, Ukraine has leaned on Western air defense systems, fighter jets, rapid-response fire teams, and interceptor drones. But even this multi-layered shield is stretched thin. Waves of coordinated strikes, especially when these Iranian-designed Shaheds are paired with cruise missiles, overwhelm both the systems and the people behind them.

That pressure sparked a breakthrough. To protect its people, Ukrainian engineers have built a new kind of weapon. It’s called Sky Sentinel, and it can fight back almost entirely on its own.

What is Sky Sentinel?

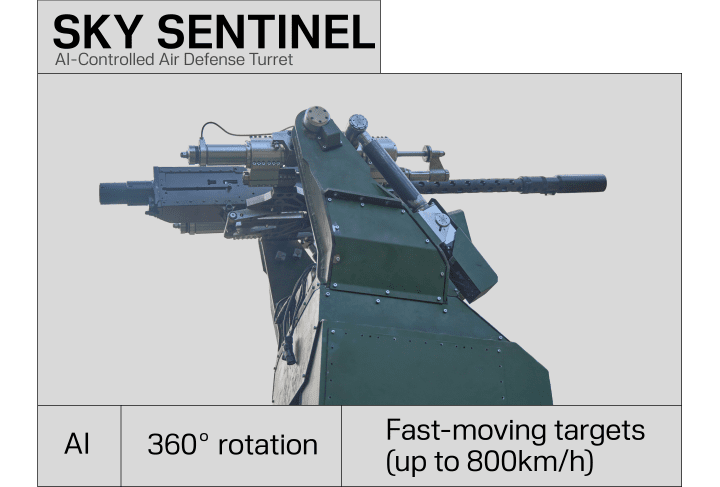

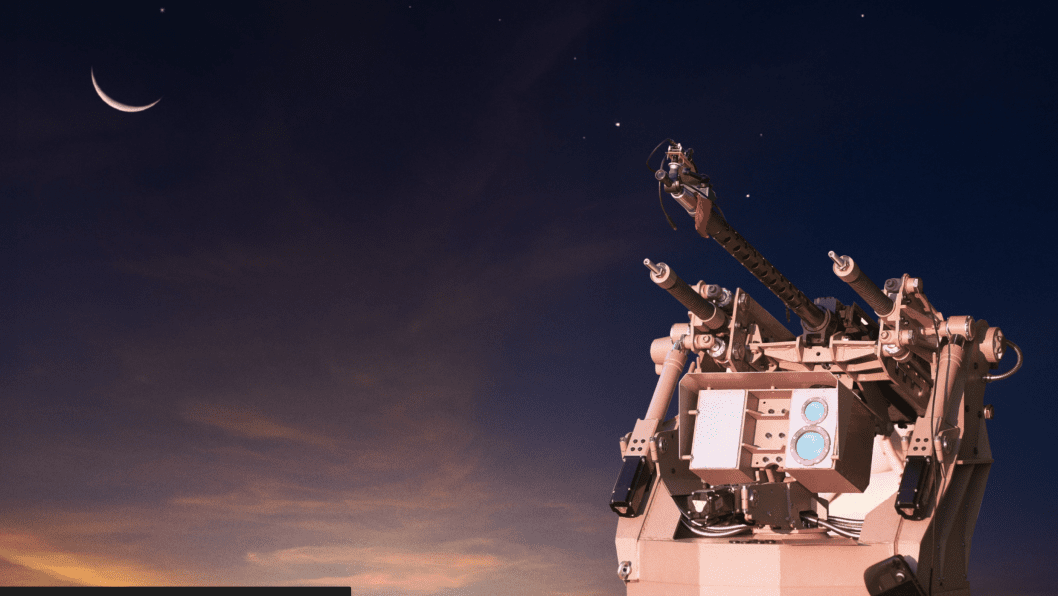

At first glance, Sky Sentinel might look like just another turret. But that’s a serious understatement. It is an autonomous, AI-controlled air-defense turret, equipped with a heavy machine gun and capable of 360° rotation. It can strike a Shahed-136 at the right range, or even a drone half its size. In fact, during field tests, it successfully hit targets five times smaller than a Shahed. Sky Sentinel is capable of downing even a cruise missile within its effective range. Any drone or missile approaching Ukrainian cities automatically becomes a target.

To reiterate: this weapon can strike small, fast-moving targets traveling at speeds of 200, 400, even 800 kilometers per hour. No wonder it’s already earned the nickname “Shahed Catcher” (as Shaheds are Russia’s most frequently used aerial weapon against Ukraine). But its reach goes far beyond one type of drone. Recon drones, loitering munitions, cruise missiles—if it flies and enters Sky Sentinel’s zone, the system takes care of the rest itself.

What does “itself” mean here? Simply put, human intervention, such as a soldier manually aiming the turret, is not required. Deploy the Sky Sentinel into a combat position, feed it radar data, and it does the rest: detects, locks on, tracks the flight paths, calculates the shot, and fires. All on its own.

Each step in this operation is a technical challenge in itself.

First, Sky Sentinel has to tell the difference between a bird and a Shahed and won’t target any sparrows. Next, it needs to lock onto the real target without delay. From there, things get even more complex: it must calculate the drone’s speed, adjust for wind resistance, and predict the exact point where bullet and drone will collide—all in real time.

And it has to do all of that instantly. There’s no room for hesitation when the target is moving at hundreds of kilometers per hour and the turret’s firing window is limited.

But that’s just the beginning.

How does Sky Sentinel make an accurate shot?

While making this report, we spoke with several members of the Sky Sentinel team. The lead engineer confirmed all the challenges mentioned—and then pointed to a critical one few outside the field ever consider:

“One of the biggest engineering hurdles for this kind of weapon is something called ‘play’—mechanical slack.”

Even a minuscule shift of just one millimeter in the turret’s mechanisms can result in a targeting error of several dozen meters at range. That kind of error makes pinpoint accuracy impossible, no matter how well the rest of the system performs.

Now picture this: a turret that rotates 360 degrees, raises and lowers its machine gun, and rides on a trailer. It’s a machine full of moving parts.

“We had to build a system that moves a lot with zero mechanical play,” explained one of the engineers. “And not just moves, but fires. Which means it also has to handle recoil.”

The mechanics behind Sky Sentinel were designed and tested entirely in Ukraine, on training grounds and in real combat. One prototype has already seen action at the front and successfully downed four Shahed drones. Due to security concerns, UNITED24 Media cannot reveal further details.

“We’re solving dozens of micro-challenges so that everything works as a single seamless system,” said the lead engineer. “No mechanical slack, no software delays, flawless optics, and precision firing. It all has to work in perfect sync.”

Foreign components and local ingenuity

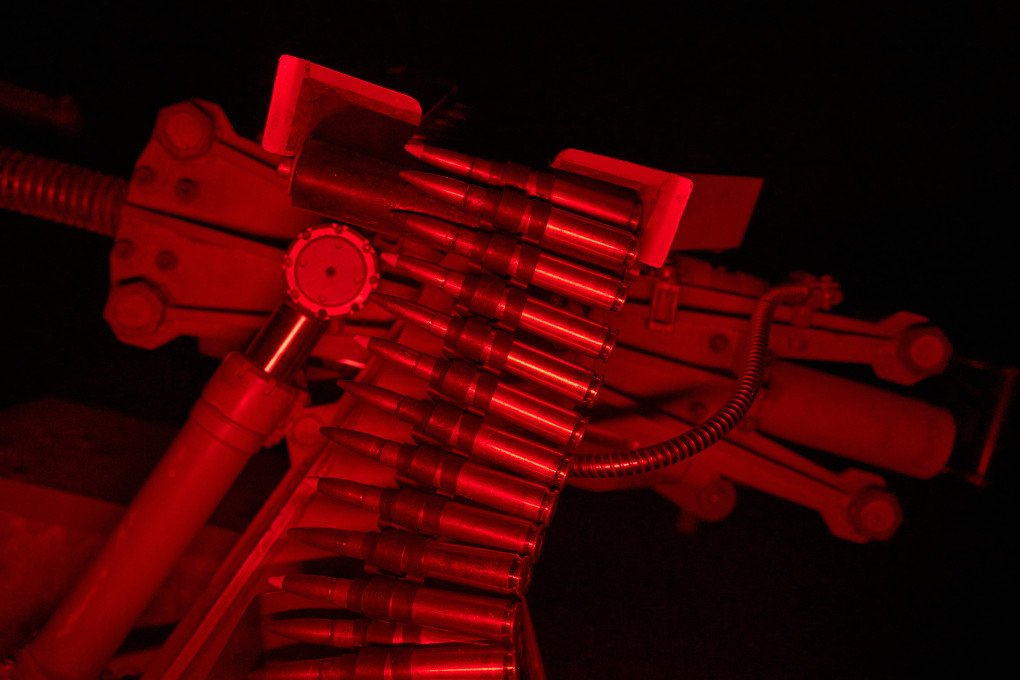

Sky Sentinel relies on foreign-made components for targeting and rangefinding—critical systems with no domestic substitutes in Ukraine today. During engagement, the weapon must maintain a constant visual lock on its target to ensure the round hits its mark at exactly the right moment.

What makes the system especially clever is its use of standard heavy machine guns with conventional bullets—no guided munitions involved. Every shot lands thanks to precise, real-time ballistic calculations

All the software that makes this possible? Written entirely by Ukrainian engineers.

Sky Sentinel on the battlefield

Sky Sentinel is versatile enough to defend both sprawling urban centers and high-risk frontline zones under constant Shahed attacks. Its maximum engagement range remains classified, but future variants are being designed for broader mission profiles.

Each unit costs around $150,000. Effectively protecting a city would require 10 to 30 turrets, which is still cheaper than a single interceptor missile from many traditional air defense systems. And with each Shahed-136 estimated to cost about $100,000, Sky Sentinel offers a cost-effective answer to a relentless threat.

The development team is now focused on scaling up production to deliver dozens of units per month. That, too, is no small task. With single prototypes, it’s easier to detect and fix mechanical play. In mass production, it’s tougher. “But it’s absolutely doable,” the lead developer says.

-29a1a43aba23f9bb779a1ac8b98d2121.jpeg)

-554f0711f15a880af68b2550a739eee4.jpg)

-ca1a63b87c648c14784932e034e42964.jpg)