- Category

- War in Ukraine

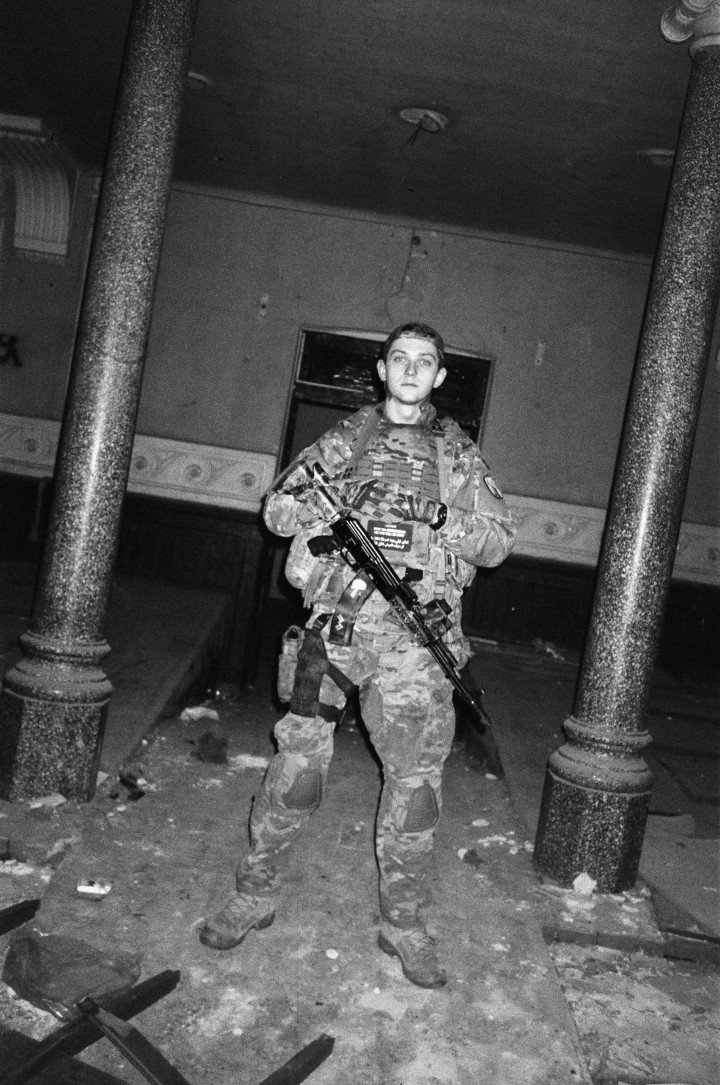

From Foreign Legionnaire to Ukrainian Sniper and War Veteran—Meet the Fighter They Call “Hepa”

As a teenager, he joined the famed French Foreign Legion. After Russia launched its full-scale invasion of Ukraine, he became a volunteer, fighting on some of the hottest fronts of the war. Legionnaire, boxer, and sniper of the 3rd Assault Brigade—callsign “Hepa”—by the age of 24, he had lived a lifetime’s worth of experiences.

“So my father tells me: ‘You’ll become a sports rehabilitation specialist,’” Hepa recalls his conversation with his father at just 17. “I ask him, ‘And how much does a regular sports rehab guy earn? Would that be enough for you?’ I didn’t think so. Then he says: ‘What, you’re going to serve in the Foreign Legion or something?’ Pretty sure he was just talking tough. But I did exactly that.”

Today, 24-year-old Hepa serves in Ukraine’s famed 3rd Assault Brigade. Born in the eastern Ukrainian city of Luhansk, Hepa attended a sports boarding school, trained in boxing, and won major tournaments. In 2014, when Russian forces occupied his hometown, his coach evacuated the team to Ukrainian-controlled territory.

At 17 and a half, Hepa traveled to France to apply for the legendary Foreign Legion—the minimum age for enlistment, with parental consent.

Notice the word “legendary”? It’s earned.

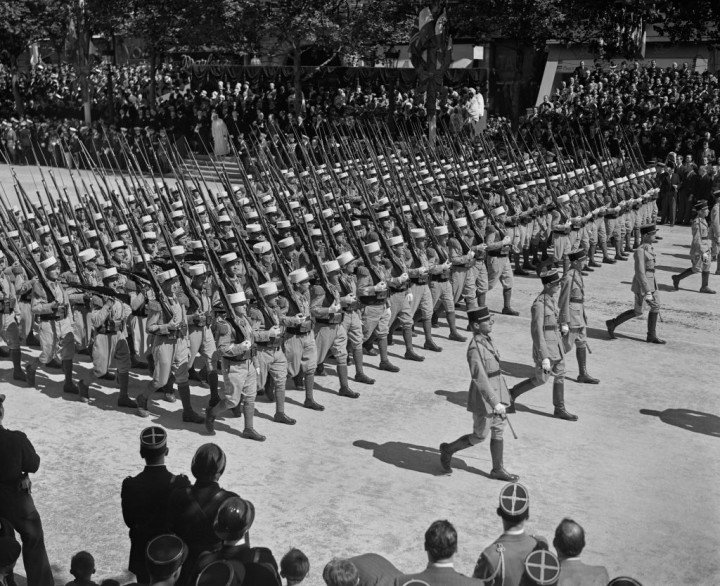

The world’s elite mercenary force

The French Foreign Legion was established in 1831 by King Louis-Philippe of France. At the time, many foreigners resided in France, but only French citizens could serve in the regular army. The Legion offered them a path into military service.

Since then, the Legion, composed of mercenaries from across the globe, has fought in dozens of campaigns worldwide. One of its defining moments came in 1863 at the Battle of Camarón, Mexico, where 65 legionnaires held off nearly 3,000 opponents for two days. When their ammunition ran out, the few survivors fixed bayonets and charged. Struck by their bravery, the enemy ceased fire and released the three surviving legionnaires. Today, the wooden prosthetic hand of Captain Danjou, who led that fight, is the Legion’s most sacred relic.

Speaking of leadership, the Legion’s current head is Cyrille Youchtchenko, an ethnic Ukrainian. In recent decades, the Legion has continued to participate in peacekeeping and combat operations in Afghanistan, Africa, Southeast Asia, and elsewhere. It now numbers about 8,000 soldiers, selected through a grueling process.

“The selection process lasted two months for me,” says Hepa. “Then four months of basic training, and after that, active service.”

The Legion’s motto is “Legio Patria Nostra” (“The Legion is Our Homeland”). Life there is strictly regulated, and contact with the outside world is limited. Historically, the Legion offered refuge to fugitives—soldiers would assume a new identity and, after several years of service, could become French citizens.

Today, the rules have softened somewhat. Applicants with serious criminal records are no longer accepted, contact with family and friends is allowed, and legionnaires can own mobile phones. However, restrictions on marriage and major purchases like vehicles still apply. Every new legionnaire receives an Anonymat—a new name, new parental names, new birthplace, and new birth date.

Tattoos are a special concern: Nazi and racist tattoos are banned, and the Legion explicitly advises candidates against “stupid tattoos”—as they put it, “If you have a little tear under your eye, you can try to join. If you have a vagina tattooed between your eyes or a penis on your arm, stay at home.”

Out of every 100 candidates, only 10–15 are accepted, preserving the Legion’s reputation as the world’s premier mercenary force.

“They really don’t accept hardcore criminals anymore,” Hepa says. “Although there are still nuances. There’s a lot more bureaucracy now. And a lot of Russians. Serving alongside them is… something. If you’re a patriot, it gets under your skin. But settling things through conflict isn’t an option—the Legion is built to suppress that. They work you so hard physically and mentally that you simply don’t have time for anything else. You must become a team, or you’re both kicked out.”

Training is notoriously tough. For instance, legionnaires aged 18–21 must complete 45 pushups; those aged 22–37 must do 50.

“I’m grateful to the Legion for what they taught me. That’s where I became a true combat soldier.”

Soon enough, everything he’d learned in the Legion proved essential.

Closing the gates to Kyiv

“When Russia’s full-scale invasion began, I was ready—bags packed, body armor on, fully geared up. We all knew it was coming,” Hepa says.

By then, he was in Kyiv, working at the iconic nightclub K41 and as a customs broker — a quieter chapter that began after he was wounded in a French unit and returned to Ukraine.

Even a few months before the full-scale invasion, Hepa tried to enlist in a brigade. “They told me I’d be a mortar driver. I said, ‘Guys, come on — a mortar crew? I barely got my driver’s license.’ So I left.”

He began calling every contact in his different military units. One responded, “Be ready. A car’s coming in two hours.”

Hepa arrived, showed his Foreign Legion documents, and was immediately accepted. That unit would later become part of the now-renowned 3rd Assault Brigade.

“I was a strong marksman even in the French Legion,” he says. “I was the only one who stayed on the range from dawn till dusk. I would’ve lived there if they let me. Shooting was my passion. So in Ukraine, I naturally became a sniper.”

During the defense of Kyiv, Hepa fought in Moschun, a small village that analysts later called the key to the Battle for Kyiv.

“We were a sniper group attached to an anti-tank company,” he says. “We had big, serious rifles — the kind that can punch through armored vehicles. But we targeted infantry too. We were angry—very angry—and if we didn’t see vehicles, we took out enemy troops. Normally, sniping is a job where you can spend hours just staring into the distance and see nothing. But here, they were charging straight at us.”

At that time, Ukrainian defenders around Kyiv were mainly using the Snipex Alligator—a 25-kg sniper rifle chambered in 14.5mm. Hepa says they often had to fire with 1932-era ammunition, making ballistic calculations nearly impossible—but it didn’t matter when the Russians were charging directly at them.

“In Moschun, it was hell,” he recalls. “They hit us with phosphorus, airstrikes, and artillery. Thanks to my experience, many of the younger soldiers looked to me. A lot of guys didn’t know how to fight yet. But I believe those who later became the 3rd Assault Brigade did a lot to help save Kyiv.”

Hepa sustained a wound during the battle.

“I looked out a window just as an 80mm mortar round landed. A plastic window frame blew out, right into my face. Blinking was agony. They told me: ‘Walk a kilometer that way. There’s an evac point.’ So I did.”

He remembers Moschun vividly. The Russian occupation of his hometown, Luhansk, in 2014 had already filled him with rage, and after Kyiv, there was even more.

Comparing the Foreign Legion and Ukraine’s 3rd Assault Brigade

Asked to compare the two, Hepa pauses for a moment.

“In some areas, we’re just now catching up. In terms of training, stages of development, they do things very smartly. But the 3rd Assault Brigade is built for real, full-scale war. Honestly, I don’t know how today’s Foreign Legion would perform under these conditions.”

“Ukraine is facing aircraft, tanks, electronic warfare, missiles—even space-based assets. Russia is literally waging war on us from space. And we’re still stopping them.”

After recovering from his injuries, Hepa fought on the Mykolaiv front as well.

“I scored my first confirmed officer kill there—960 meters out. Saw a guy with a pistol holstered, wearing multicam, gesturing a lot. That’s a signal: ‘This one’s mine.’ One shot with a .338 Lapua Magnum round—down he went. I waited to see if anyone would help him. Nope. They scattered. Later, they told me he was a major, evacuated with an honor guard.”

Unlike Moschun, sniper work elsewhere was slower. It often took days or even weeks of recon before a shot.

Still, sniper life was grueling:

“When you’re alone in the woods, it messes with your head. You know the enemy can come at you from any side. Often, we didn’t even carry sidearms to save weight—just a grenade to avoid capture. We all knew what happened to prisoners—photos and videos of Russian torture. And if they caught a sniper? They wouldn’t even post those pictures.”

Later, Hepa moved away from sniping.

“At 24, my health’s already wrecked. Three concussions, lots of frostbite—occupational hazards. Now, it’s the era of drones. To a drone operator, I’m just a warm blob lying there with a $20,000 rifle. I can run or not run—same result. Sniping’s becoming obsolete.”

One of his injuries came from a landmine explosion:

“No matter how good you are, how well equipped, you hit a mine, it’s over. We were just in a Mitsubishi L200, no armored capsule. It exploded. Two friends died. So many good guys have been lost.”

Today, Hepa is focusing on recovery and helping his unit with personnel matters. He has no plans to leave the army.

Asked about future plans, he muses he might work in security or tactical consulting abroad.

And what would he say to Russians?

“Nothing to say. I’m not about words. I’m about actions. And I’m doing them.”

-0666d38c3abb51dc66be9ab82b971e20.jpg)

-29a1a43aba23f9bb779a1ac8b98d2121.jpeg)

-74e27e09e312d1639f24e75f6233ccd5.png)

-24deccd511006ba79cfc4d798c6c2ef5.jpeg)