- Category

- War in Ukraine

How Do You Rebuild After a Russian Missile Strike? In Sumy, Cleanup Is the First Step

After Russia’s April 13 missile strike, Sumy’s residents are clearing rubble not just to rebuild, but to heal. In a city under constant attack, cleanup has become a quiet act of resilience and recovery.

Sumy’s Institute of Applied Physics is across the street from the Business Technologies University, where the second missile hit on April 13. The neoclassical building dates from 1895 and sustained the brunt of the shockwave. Inside the building, the doors are slightly curved and pillars are split through the middle. Everything warped under the pressure. In the entrance is a clock, stopped at exactly 10:23 am, the exact time of the blast.

Down the center of Sumy’s Academic Lane, the two buildings targeted by the missiles are just minutes apart. It’s a bright day, approximately one week after Russia’s attack, which killed 35 people and injured over 100. Across the street from the destroyed building, Serhii a Sumyelektroavtotrans Network electrician, wearing a grey and orange construction suit, is laying down wires to get the trolley bus up and running.

Serhii arrived on the scene 15 minutes after the second strike. “It’s tough seeing all this,” he says after a pause. “We’re usually the first ones out there.” The job entails arriving as early as possible and assessing the damage. “You don’t get used to it, but you learn to act,” says Serhii.

The shockwave from a ballistic missile is a violent, instantaneous release of energy that moves faster than the speed of sound. When it hits, the pressure is immense, strong enough to collapse buildings and leave anyone nearby gravely injured or killed.

This surge of force, known as overpressure, can rupture internal organs and burst eardrums. A powerful blast of wind then follows, sending shards of glass, metal, and debris flying across wide areas.

In the April 13 strike, Russia used ballistic missiles armed with cluster munitions, warheads that release dozens of smaller bomblets mid-air. Designed to cover wide areas, these submunitions increased the risk to civilians, especially as large crowds gathered for Palm Sunday, a major holiday in Ukraine.

Swift cleanup efforts following Russian strikes

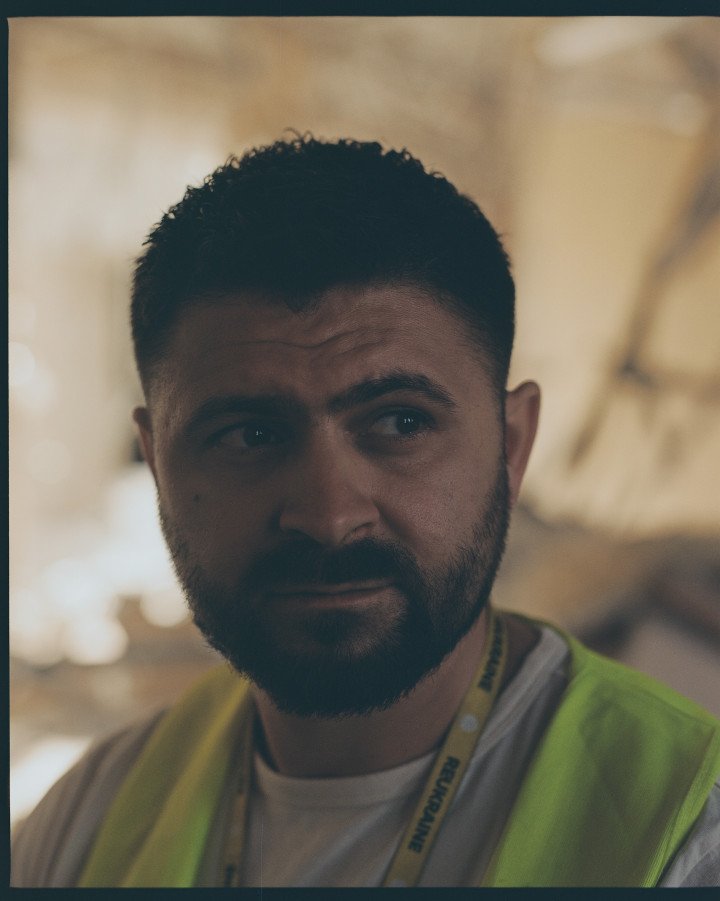

Driving into Sumy, you notice how clean and well-kept the city is. The streets are swept, windows are boarded up with sheets of plywood, and the local parks are groomed. Oleksii Kliuiev, head of Sumy’s Dobrobat—a Ukrainian volunteer organization focused on the rapid repair of damaged homes and social infrastructure—stands outside the Congress Centre of the State University, where the first missile struck. Dobrobat has been on site for a week, with 10 to 15 volunteers actively clearing the area.

“We respond to almost every strike,” says Kliuiev. “After each attack, we gather ten to 30 volunteers and agree on time and location. We respond to all hits that are not connected to military targets.”

Kliuiev does not lack a sense of humor. He’s quick, business-savvy, and a lifelong resident of Sumy. Before the war, he recalls that every Easter weekend, he and his friends would go on a three-day fishing trip. Now, he doesn’t have time for that.

Sumy has become a frontline city, hit day and night by a barrage of Russian missiles, artillery, and Shahed drones. “Anyone could be the next victim, volunteers included,” says Kliuiev. “That shared understanding brings people together,” he adds.

“Anyone could be the next victim, volunteers included.”

Oleksii Kliuiev

Head of Sumy Dobrobat

Dobrobat began operating after the Sumy region was liberated from Russian occupation, founded on April 28, 2022. Initially, the city of Sumy itself wasn’t heavily damaged, but nearby occupied towns like Trostianets were.

Kliuiev drives around the city, pointing out all the apartments, schools and hospitals that have been hit by missiles and drones. The quick cleanup after strikes is common across Ukraine and underscores what Kliuiev explains as “Efforts to help people return to normal faster.” It also enables people to stay in their homes and avoid evacuation. “Psychological help starts with action, knowing someone is there for you changes everything,” he says.

Sumy volunteers fill gaps in emergency response

Because Sumy is relatively small, Dobrobat and its volunteers are sometimes the first to arrive on site to perform basic access support. Russia’s double-tap tactic makes this particularly dangerous, as there is no way to know if an initial strike will be followed by another.

Doors can jam and lock under blast pressure, explains Kliuiev, “In multi-story buildings, you need many hands to access rooms quickly, especially when someone is bleeding and time is critical.” Only after these preliminary actions are completed and the area is deemed secure does the clearing and securing of the structure begin.

“We formed to support our main partner, the State Emergency Service (DSNS), especially after meeting DSNS officer Oleh Strilka during joint responses,” says Kliuiev. The DSNS has many responsibilities, including demining, evacuations and firefighting, but limited personnel. Dobrobat fills the gaps with basic construction and cleanup.

The motivation to rebuild

On Good Friday, a Russian Shahed drone struck a bakery as it was in the final stages of preparing traditional Ukrainian Paska cakes , killing one man. A few hours after the blast, rubble is being cleared, workmen pass holding ladders as others prepare the plywood to board up the windows. A bakery employee sweeps the broken glass that’s shattered all over the reception desk.

The inside of the building is heavily damaged, meaning that many of the employees have lost their jobs to the Russian strike. Most people don’t feel like talking, reminding us that they just lost a colleague and friend. One man does, but prefers to stay anonymous. He shows us what’s left of the Shahed, a tiny scrap of twisted metal.

Strilka, sits in his car outside the bakery. Over the hum of the crane clearing rubble, he says, “Now this has become the norm. It wasn’t like this before. It happens every week. Civilian infrastructure is the target now.”

Strilka notices that people immediately come together after strikes, ready to clean up. “It’s hard for people, but I think they’re becoming more united,” he says. Strilka believes the motivation hinges on the will to restore things to how they were. People, he says, “immediately start doing something.”

It’s clear that, like Kliuiev, Strilka serves as a motivating force for the city of Sumy. When Russia’s full-scale invasion began, he described the city of Sumy as abandoned. “Only rescue workers and civilians remained.”

Strilka finds the motivation to act and organize from the people of Sumy themselves: “Ordinary civilians went to the enlistment office, picked up weapons, self-organized, and defended Sumy. There was an old man who rode to the enlistment office on a bicycle with four rifles. When Russian tanks rolled in, people came out and sang the anthem. The civilians stepped up.”

Dmytro Hrebeniuk is 25 years old and head of the rescue squad for special assignments in the city of Zhytomyr. Sent to Sumy to help with rescue and maintenance, he’s in full rescue gear, a harness around his waist. Hrebeniuk comes down from the roof of the bakery, explaining they are there fixing the infrastructure, “So that people can get back to work as soon as possible.”

“After three years of war, you’re just like a robot,” adds Hrebeniuk, but emotions do come up eventually, he says. DSNS workers have access to rehabilitation programs and sanatoriums in Odesa and the west of Ukraine to take a break, but in reality, dealing with these challenges takes a backseat. Most importantly, Hrebeniuk adds, “You do your job.”

Rebuilding with care: a focus on precision and efficiency

Kliuiev drives us to the site of a Russian Shahed strike, infamous for images of a woman hanging upside down from the rubble, though Kliuiev believes she survived. The strike killed 9 people, injured 13, and led to the evacuation of 120. The windows of the tall apartment buildings gleam in the sunlight, while the walls in the center are blown out, exposing the interior. Shoes are neatly lined up in the hallway, and the refrigerator door hangs open. As Kliuiev tries to recall the date of the strike, a nearby boy playing on his scooter quickly answers: it was on January 31.

The aftermath of a strike hits one place, but affects everything around it, says Kliuiev, gesturing to the apartment blocks surrounding him. People lose their jobs, some are displaced, and children have to move schools. “What do we do with Dobrobat?” He states, “We enable people simply to continue living. It takes a lot of time and effort to return to normal during a war.”

The care that goes into rebuilding, replacing windows, or cleaning away debris is comparable to patchwork; the neater it’s done, the better it looks. For Kliuiev, though it seems trivial, aesthetics are important.

“When we started working, we used a very careful approach, making sure the windows we boarded up looked neat,” he says.“For example, if it’s only the insulated glass that was damaged, we seal without damaging the frame so that people can just remove the plywood sheet and insert new insulated glass there. We try to do it very carefully.”

Dobrobat volunteers build a family-like bond

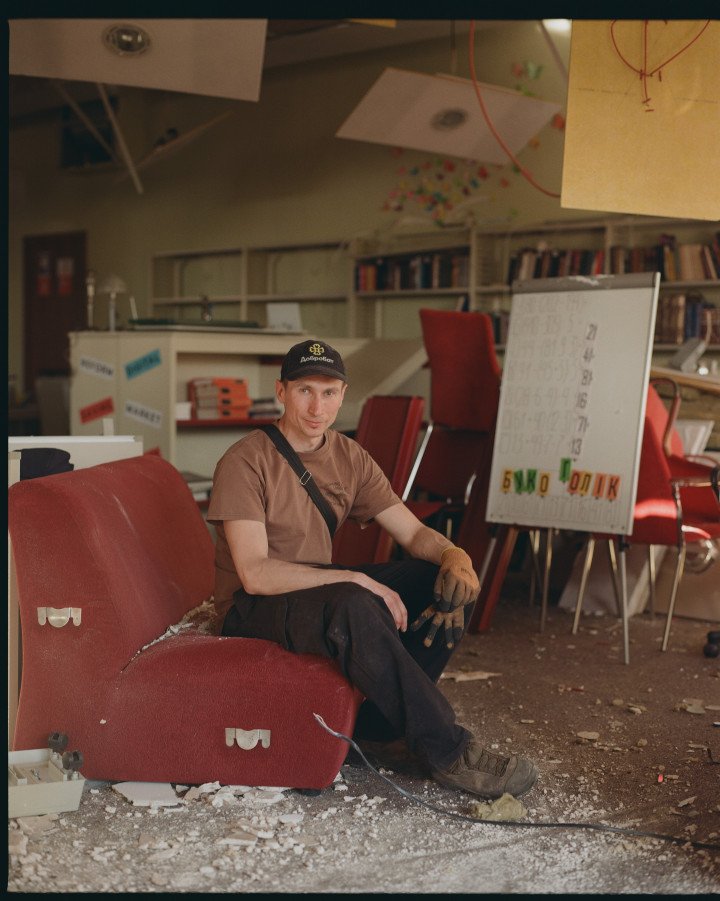

Back at the Congress Center where the strike took place, we meet volunteers working with Dobrobat. Kliuiev describes Sasha Zavaliy as “the backbone of our team.” A skilled builder who has worked in construction since the age of 13, Zavaliy, around 35 years old, cuts a strong and lean figure. He joined Dobrobat in 2022 and is currently working to clear the Congress Center strike site. For him, rebuilding helps make sense of the current situation.

“I don’t want to just sit and watch everything fall apart, then later say I couldn’t do anything, because I lacked the strength to step in. This is helpful for me too.”

Sasha Zavaliy

Dobrobat volunteer in Sumy

“Now we have a well-developed process,” he says. “We arrive, assess the site, check where the windows are wooden or plastic, and what can be patched or sealed. Everything is organized. We mark, cut, and measure. Everyone knows what to do.”

The spaces where Zavaliy works have witnessed death and injury, leaving tangible and intangible marks. Zavaliy hesitates before bringing this up, “It’s knowing people died there. You can feel the energy in those places. The first time I felt it deeply was in Trostianets. In one five-story building, on the fourth floor, I found bloodstains…That’s the hardest part.”

Another volunteer, Yulia Suprun, decided to join Dobrobat when a strike hit 500 metres from her house. She’s soft-spoken, and her long hair catches the sun. “On the first and second days, a lot of people come. Everyone joins in,” she says. After an attack, she explains, people experience a surge of energy, and this motivates them, but as projects extend over time, “It seems like no one cares anymore.”

Suprun believes rebuilding should be completed, Dobrobat works up till the end. The team is made up of a core group of regulars who have been working together for several years now. Suprun attributes her motivation to them, “We’re all in it together, I think we’re like one family,” she says.

Surviving the strike

Inside the dark Congress hall, in the middle of the building, a gaping hole surrounded by chunks of cement is cordoned off. Volunteers are all around, sweeping, organizing, and carrying furniture out. The sounds of drills can be heard on the second floor.

“This is my city,” says Vika, who was one of the first volunteers on site after April 13. She’s standing on the first floor, insulation wool and plaster dust spotting the air. She pauses her work, holding her hands behind her back.

“People are very thankful that we come, help them, and clean up. We come right away in the first days and do everything. It’s very important to come quickly.”

In her orange construction vest, the blue of her eyes is magnified. “I’m scared for my daughter, for my grandson, scared for everyone here. But my motivation has actually increased.”

Kliuiev guides us up the stairs, through the wreckage. We pass the library, where the floor is strewn with hundreds of books, Plato’s The Republic, Vasari’s Lives of the Painters, Sculptures, and Architects, and Saint Augustine’s The Confessions. Among the piles of rubble, books, metal and plaster, Kliuiev looks out the window at the street below. Teenagers laugh while checking their phones, across from them, an old man sits on a bench staring into the distance. When asked what will happen to all the books, Kliuiev simply responds, “I don’t know.”

Deepest thanks to Amira Barkhush, Oleh Strilka and Oleksii Kliuiev.

-554f0711f15a880af68b2550a739eee4.jpg)

-4814ee2c5b90beeb19999082bb535df7.jpg)

-5c1ba3fedbff10460136c89c0d3db7e9.jpg)

-a2a5e9c9c8682c0d90a89c3b327af483.png)

-29a1a43aba23f9bb779a1ac8b98d2121.jpeg)

-f682ba744ef5abc05c60bcc8c2e86500.jpg)