- Category

- War in Ukraine

How Drone Warfare Is Forcing Ukraine to Rethink Military Uniforms

In Ukraine’s drone-dominated war, camouflage is moving beyond patterns and colors. With thermal imaging, aerial surveillance, and AI-driven detection reshaping the battlefield, Ukrainian forces are turning to new uniforms, anti-thermal suits, and heat-masking cloaks designed to evade sensors as much as human sight.

Ukraine has approved a new military pattern optimized for camouflage, expanding official uniform options beyond the long-used MM-14 “pixel” design, as modern warfare increasingly renders visual concealment secondary to detection by sensors, drones, and artificial intelligence.

The newly approved pattern, MM-25, resembles Western multi-environment camouflage designs and will be introduced through limited trial batches rather than a full replacement, Ukraine’s Defense Ministry’s logistics department says. The decision responds to repeated requests from frontline units that have already been using similar patterns purchased privately.

But among soldiers, designers, and military historians, the shift has brought to light a lesser-known fact.

“The actual camouflage pattern doesn’t really matter that much,” Nick, a sergeant in the Ukrainian Armed Forces, said. “As long as you’re wearing neutral earth tones, after a while, the uniform gets dirty and blends in anyway. The real issue now is IFF—identifying friend or foe.”

From bright uniforms to neutral ground

The idea that soldiers should blend into their environment is relatively new in military history. Until the late 19th century, armies operated under what historians call the imperative of visibility. Commanders needed to see their troops through thick smoke and chaos, and brightly colored uniforms served command and control rather than protection.

At the turn of the 19th century, this logic began to collapse. Firearms multiplied, their range and caliber increased, and lethality rose sharply. Individual initiative replaced tight formations.

One of the earliest figures to challenge the old model was Lieutenant-Colonel Charles Hamilton Smith, a British Army officer and scientist who, around 1800, conducted one of the earliest systematic experiments on uniform color to determine how firearm accuracy changed with color visibility. Arguing against colorful uniforms in favor of the least visible clothing possible, Smith’s reasoning was practical rather than aesthetic.

The transformation accelerated when French engineer Paul Vieille invented smokeless powder, known in France as Poudre B. For the first time, battlefields were cleared as dense smoke dissipated, allowing soldiers and enemy marksmen to see farther. Combat shifted from a two-dimensional plane to a vertical plane, changing military observation and engagement.

That framework began to collapse in 1911, during the Italo-Turkish War, when Italian forces deployed aircraft for reconnaissance over Libya. The shift accelerated rapidly. By 1914, at the outbreak of World War I, aircraft had been absorbed into European armies as tools for observation, artillery spotting, and battlefield mapping. Within a year, aerial photography became routine.

Camouflage as deception, not decoration

By World War I, camouflage was institutionalized, expanding beyond uniforms to artillery, buildings, and entire positions. Painters, architects, engineers, and craftsmen were recruited to create nets, false structures, and decoys. Camouflage became both concealment and deception: hiding real assets while displaying fake ones.

France led this transformation, followed by other powers. Italy pioneered printed camouflage fabric in 1929 with the telo mimetico, originally designed as a tent cloth. After Italy’s capitulation in 1943, German forces seized vast stocks and turned them into uniforms. Units in Normandy could later be identified by their Italian fabric.

Crucially, camouflage became an identity marker. Elite units adopted distinctive patterns. Reversible uniforms appeared, offering one side for forests, the other for snow. Cost often dictated limits.

German documents even advised soldiers on the Eastern Front to steal bedsheets from civilians to improvise winter concealment. After World War II, most armies standardized camouflage. The Cold War favored uniformity over experimentation. That changed again at the turn of the 21st century.

Pixels, science, and failure

Modern digital camouflage emerged not from visual criteria, but from science. Canada pioneered contemporary pixelated patterns in 1997, after extensive testing showed that small geometric shapes disrupted silhouettes at multiple distances better than organic forms, leading to the development of CADPAT (Canadian Disruptive Pattern).

The idea was controversial. Convincing militaries that something “unnatural” could blend into nature proved difficult, yet testing confirmed the results.

The US Marines adopted MARPAT, cementing pixel camouflage as both functional and symbolic. The US Army’s later Universal Camouflage Pattern, introduced in 2004, became a cautionary tale. It performed poorly in Afghanistan and Iraq, with complaints reaching Congress. Investigations revealed it had not performed well in initial tests, and the pattern was eventually replaced by Multicam after new trials.

“Today, camouflage is tested by machines,” explained one European military researcher involved in pattern development.

“Visual sensors, thermal sensors, different distances, different backgrounds. Jungle, desert, urban terrain. If it doesn’t perform across these parameters, it fails.”

From Soviet oak to pixel Ukraine

After independence, Ukraine inherited Soviet camouflage stocks, primarily the VSR-84 pattern, known as “Butan” or “Dubok.” The pattern evolved through local modifications and was used across all branches, including missions in Iraq.

In 2014, amid the first phase of Russia’s war against Ukraine, the Armed Forces transitioned to MM-14, a digital pixel camouflage inspired by Western designs. It was meant to function across urban, forest, and steppe environments. For years, MM-14 defined the Ukrainian military’s appearance.

But supply realities intervened. Western gear flowed in. Soldiers compared fabrics under combat conditions. “Pixel works okay in the fall when it’s muddy,” Nick said. “But when it turns green, it stands out more. And honestly, the fabric just isn’t as good.” Multicam spread rapidly. Not because it blended better visually, but because it was lighter, more breathable, more durable.

Former Defense Ministry advisor Dana Yarova made the same point bluntly. Troops, she wrote, wear Multicam because the fabric withstands stress and does not wear after days in a dugout. Pattern came second. MM-25 formalizes that shift without fully embracing it, though the ministry insists it is an additional option, not a replacement.

IFF in a world of lookalikes

The unintended consequence of Multicam’s spread is confusion. “Both sides wear it,” Nick said. “That’s why you see tape on arms. We need to know who’s who.”

IFF, identification of friend or foe, has again become the primary function of uniforms, echoing the 19th-century imperative of visibility, but inverted. Soldiers must be invisible to the enemy yet recognizable to each other. Yurii Hudymenko, head of the Anti-Corruption Council under the Defense Ministry, said camouflage also signals role and status. “For special forces, it’s protection and identity,” he said. “Ground troops wear pixel. Special units wear multicam. That distinction matters on the line.”

Yet, that distinction is increasingly eroded. “A lot of fighting now, camouflage isn’t that important,” Nick said. “Thermal drones see you anyway.” Modern reconnaissance relies on infrared sensors, radar, and AI-assisted image recognition. Against these systems, color patterns matter little, and that battlefield solution is shifting toward function rather than fabric.

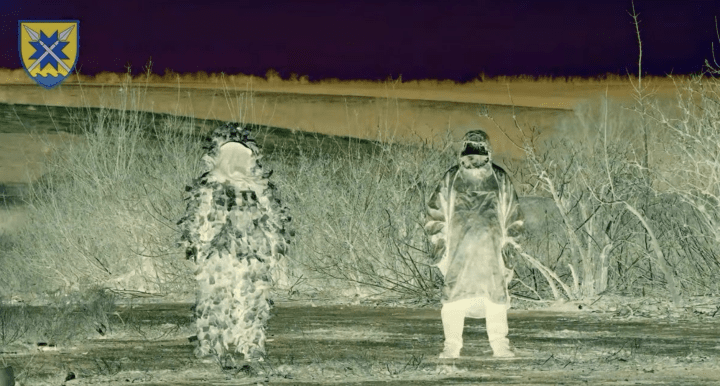

Ukraine introduces anti-thermal gear to reduce drone detection

Ukraine’s 56th Separate Motorized Infantry Mariupol Brigade has begun using anti-thermal suits designed to reduce soldiers’ visibility to Russian thermal imagers and reconnaissance drones, the brigade’s press service reported on March 19. A video released by the unit shows personnel moving across open terrain, with their heat signatures largely blending into the surrounding environment when viewed through thermal imaging.

The brigade said the suits are intended for reconnaissance units, assault groups, snipers, and evacuation teams. Developers involved in the project say the garments mask body heat by reflecting the thermal characteristics of the surrounding environment, reducing detection risk, particularly in cold weather when infrared signatures are more pronounced.

Separately, Ukraine’s Ministry of Defense said it is testing fabrics for anti-thermal-imaging ponchos intended to conceal soldiers and equipment. Five fabric samples are undergoing evaluation for their ability to absorb infrared radiation while remaining flexible, weather-resistant, and suitable for camouflage, according to the ministry.

Ukrainian forces have also used Czech-made thermal-masking cloaks produced with InfraHex material, primarily by special units. The poncho-style cloaks can be deployed quickly and are designed to suppress thermal signatures visible to drone-mounted infrared cameras, with the manufacturer stating they can reduce detectable heat output by up to 96%.

Camouflage type | Description |

Visual camouflage | Traditional patterns are designed to disrupt the human eye. Includes pixel, woodland, desert, snow, and multi-environment designs. Increasingly limited against sensors. |

Multi-environment camouflage | Patterns like Multicam and MM-25 are intended to perform acceptably across terrains rather than optimally in any one terrain. |

Thermal camouflage | Materials and coverings that reduce or distort infrared signatures. Includes anti-thermal blankets and reflective survival sheets, now widely used by individual fighters. |

Structural camouflage | Nets, screens, and physical coverings that break recognizable shapes. Effective only when angles are disrupted, not simply draped. |

Adaptive and dynamic camouflage | Systems that actively manipulate thermal output. British company BAE Systems has demonstrated its Adaptiv system, using hexagonal panels to mask vehicle heat signatures. Demonstrations have shown tanks disappearing on infrared while projected images are displayed instead. |

Deceptive camouflage | Decoys, false positions, dummy vehicles. Widely used in Ukraine to draw fire and confuse drones. |

The frontier: AI versus concealment

Detection systems are increasingly shaped by artificial intelligence trained on large public image datasets, allowing machines to recognize vehicles, soldiers, and recurring patterns more quickly than human observers. Some researchers warn that “poisoning” (interfering with existing data) training data could, in theory, confuse such systems. The idea is simple: corrupted data in, corrupted recognition out. In practice, it is extraordinarily difficult.

More immediate are physical countermeasures, such as adaptive skins, thermal nets, and multispectral screens introduced after 2021, which can simultaneously mask radar, infrared, and visual signatures.

Yet durability remains the question. Can such systems survive rubble, abrasion, and urban combat? What happens when panels break or tiles shatter? Smoke remains effective but costly. New research explores “smart” smoke that blinds the enemy while allowing friendly forces to see through it, though deployment risks revealing position.

Where MM-25 fits and what other armies can learn from Ukraine

MM-25 does little to resolve the broader questions now facing military concealment, nor was it designed to. Its purpose is narrower and more pragmatic. It brings official procurement closer to what frontline units have already adopted through informal channels, addresses long-standing complaints about durability and fabric quality, and formalizes the use of patterns that special units have relied on out of necessity rather than regulation. In that sense, it offers flexibility and institutional acknowledgment, not a conceptual breakthrough.

The trajectory of camouflage in Ukraine is moving elsewhere. Increasingly, concealment is constructed around vehicles rather than uniforms, applied through layered materials, thermal coverings, nets, screens, and modular systems designed to alter how objects register across multiple sensors. As aerial surveillance and automated detection become dominant, the problem shifts from deceiving the human eye to managing signatures in data. In a battlespace observed from above and interpreted by algorithms, camouflage really is no longer primarily about blending into the environment, but about reducing legibility altogether.

-554f0711f15a880af68b2550a739eee4.jpg)

-29a1a43aba23f9bb779a1ac8b98d2121.jpeg)

-76b16b6d272a6f7d3b727a383b070de7.jpg)

-f88628fa403b11af0b72ec7b062ce954.jpeg)