- Category

- War in Ukraine

How Ukrainian Soldiers and Their Drones Became the Frontline’s Unstoppable Duo

Meet the drones and their operators—pairs forged in war, bonded by survival. In Ukraine’s fight against the Russian invasion, these robots have become more than weapons. They’re comrades, partners in arms, serving side by side with the soldiers.

We gathered firsthand accounts—told in their own words—of six soldiers from the 3rd Assault Brigade about the drones they fly, fix, fight with, and sometimes even save. Their stories and faces appear in intimate portraits that reveal the link between human and machine.

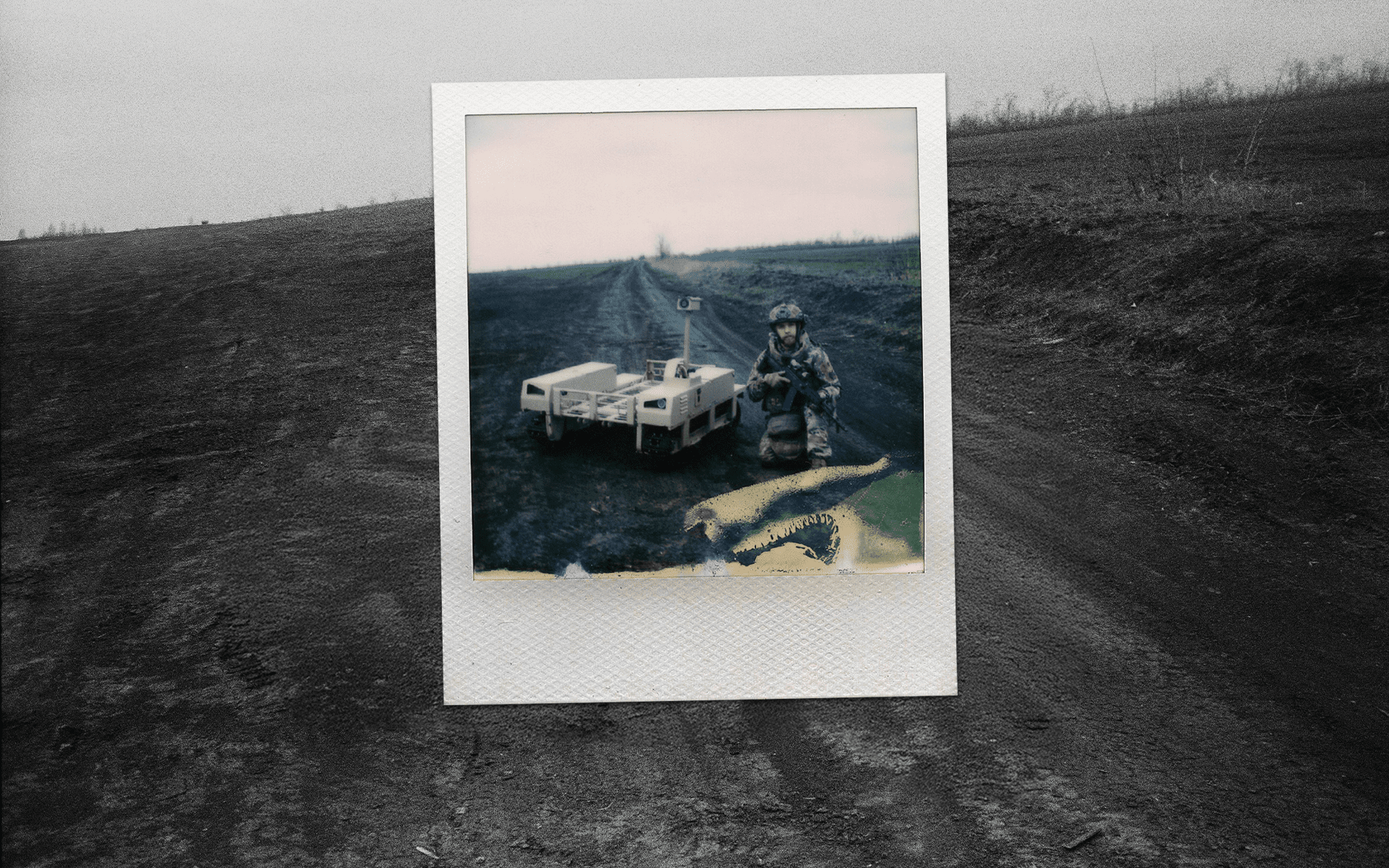

Bar, 22, and his “TerMIT” robot

Before Russia’s full-scale invasion, I managed a bar. But I was raised with the belief that protecting your country is your duty. So at 20, I walked into a recruiting center, signed a contract, and became one of the first soldiers in the 3rd Assault Brigade, which was just forming at the time.

At first, I served in an assault unit. I took part in the Bakhmut operation and later Avdiivka. At some point, the brigade decided to form a ground robotic systems (GRS) unit. I was one of the people who helped get it off the ground.

I’ve been working with the “TerMIT” robot from the start. It’s a solid logistics platform, really well-designed, and it almost never gives us problems. It’s also easy to modify when needed. However, it’s ideal only in dry conditions. In heavy mud or difficult terrain, not so much. In those cases, it’s really only usable for one-way trips.

These ground robots are our brothers-in-arms, and we never leave our own behind.

Bar

Ukraine’s 3rd Assault Brigade soldier

Right now, the two main areas we’re focused on improving are connectivity and mobility. We’ve found a good communication system, and with it, we can now operate at a solid range of 20 to 30 kilometers.

For the Russians, my TerMIT is a prized target. Our robots have been hit with mortars, suicide drones, bomber strikes, and Grad rockets. Yeah, sometimes they’ve gotten lucky. But our teams are so well-trained and professional that we often manage to recover robots even with blown-off wheels or broken tracks. Even when a GRS is fully destroyed, we still plan an evacuation and retrieve it at the first opportunity. Often, one drone evacuates another, since it’s too dangerous to send in other equipment.

These ground robots are our brothers-in-arms, and we never leave our own behind.

Berlin, 28, and his “Vampire” drone

I signed my contract in 2023. Initially, I planned to join the Marines, but at the assignment point, someone came over and said, “Come join the 3rd Assault. We’ve already made arrangements.” So I joined. Before the army, I worked with agricultural drones, so when I joined the unit, I went straight into UAV work.

My first combat mission was in the Avdiivka direction. Even with prior drone experience, it was a bit scary at first—this is war, after all. You’re flying blind from a trench, terrified that even the slightest mistake could send those kilograms of explosives crashing back down on you. A year ago, I wouldn’t have dared fly as low as I do now, but I’m fully confident in the technology now.

My drone is called the Vampire. It can carry a serious payload—a lot of kilos—and when it hits, it hits hard. Loud, heavy blasts. You can really feel the power. We usually load four munitions, which gives us flexibility to hit different targets. My main focus is enemy bunkers. Other drones are better suited for hitting vehicles.

Me and my Vampire—we mostly work in the dark.

Berlin

Ukraine’s 3rd Assault Brigade soldier

One night, we destroyed a Russian ammo depot just before they were about to launch an assault—the whole attack got scrapped. At first, we couldn’t find any targets. Then I switched from thermal imaging to a standard camera and spotted a small light in the treeline. We dropped a munition on it. Turned out to be the entrance to a bunker where munitions were being stockpiled. The explosion lit up beautifully. My dream is to take out a valuable stationary electronic warfare system.

The “Vampire” is a true workhorse. It can fly up to 20 kilometers, although a larger payload means less range. We usually operate near the front line. The closer we are, the farther we can fly. That’s critical.

A typical day for a Vampire operator is actually night. We mostly work in the dark. But I can be at the controls for nearly 24 hours straight, then someone swaps in, I get a short rest, and then it’s back to flying again.

My closest call came recently. A buddy and I had pulled up to a position and were unloading the truck when, out of nowhere, something flew right between us and exploded about 50 meters away. A Russian tank had fired at us. The shell flew directly between us while we stood side-by-side. Luckily, the shrapnel didn’t spread far. That moment stuck in my head like a photo—a shell passing straight between us. But we kept working. We had a mission to get food and water to frontline troops who couldn’t be reached any other way.

Swift, 34, and his FPV drones

Before Russia’s full-scale war, I was an IT project manager. My callsign is “Swift.” Here’s a little story: one time, my wife and I found a tiny baby bird, raised it, nursed it, and released it. The guys liked that story, and the name stuck.

I joined the 3rd Assault after training at our FPV drone school, Kill House. At the recruitment center, a battalion rep approached me, and the rest is history.

I fly FPVs. Mostly, we go after enemy cannons, mortars, tanks, and other gear. Probably our most successful mission was taking out a T-72-based “barn” tank with a single drone. These are supposed to be FPV-proof—they’ve got jammers, metal cages all around. But we got lucky. One drone—and not even a perfect one, it was already losing signal—managed to hit just right and burn that tank down.

But I’ve still got a couple of scores to settle.

First up, the Soviet 120mm artillery system, the “Nona.” I’ve seen them plenty of times, even landed three hits, but I still haven’t managed to really catch one clean, to watch it blow and burn. It’s become a bit of an obsession now. I have to finish it.

Second—helicopters. They fly around like they own the place. I’ve seen them close up on the screen, but haven’t hit one yet. Though yeah, there have already been cases in this war where FPVs have taken choppers down. So when we see one, we always try to chase it. Totally not our specialty, but man, it would feel so good.

One day, we will take down that damn helicopter.

Swift

Ukraine’s 3rd Assault Brigade soldier

We’re about three kilometers from the front. FPV operators are hunted, but we try to find the Russian operators as well. Everyone is deeply dug in. The most dangerous moment? Definitely getting in and out of position. For artillery to hit you dead-on, you’ve got to be really unlucky. But entry and exit are the riskiest times.

We mostly work at night, hunting enemy equipment. Once, our drone hitched a ride on a Russian truck. We caught up to a “Ural,” but they jammed our signal, and the cargo bed had a net. The drone didn’t have enough punch to detonate—it got stuck, and we ended up riding on top of that truck for 4 kilometers, with music playing, alongside the Russians. Didn’t explode, unfortunately. But hey, hitchhiking, drone-style.

I love FPVs—the action, the rush. Other operators say it’s too wild, makes them nauseous in the goggles. But I’m good with it. We can go through 70 drones in a single run, easy. Sometimes someone beats you to a target, but we usually make it in time. And one day, we will take down that damn helicopter.

The civilized world should support Ukraine. We share the same values. If we fall now, they’ll just have to support someone else later, but at a much higher cost.

Kuzma, 35, and his “Avenger” strike drone

I first went to war in 2014, got out in 2019, and spent some time traveling the world. When Russia launched its full-scale invasion, I came back to serve.

Command must’ve seen something in me, because they sent me for drone operator training. I flew Mavics, I can operate Vampire, and now I work with the Avenger. It’s a strike drone that can hit armored vehicles with shaped charges and use fragmentation rounds on everything else.

I’m fully satisfied with this bird. It’s really well-balanced — so much so that if you tried to fix its weak spots, it might mess with the strong ones.

Every target we take out is the result of teamwork: the scouts who find it, the analysts who verify it, and then us. We’ve already destroyed tanks, howitzers, all kinds of equipment. But what gives me the most satisfaction is hitting electronic warfare systems. In theory, those are supposed to block drones, and here we are, blowing them up.

Still, I’ve got a dream—to hit something that causes a massive explosion. Maybe a thermobaric “Solntsepyok” or something like that. Something that erupts so big I can see it from my position.

One time, I got close. I was already in the air, flying out to a target, when we got word the mission was canceled—poor target confirmation. But I thought: I’m already here, might as well strike. The explosion that followed… Yeah, we definitely hit something important. Turned out it was an ammo depot.

I think drone operators should try flying as many platforms as possible. The more you fly, the more experience you can carry over to other drones—it just makes you better. I’d love to fly a US Reaper, that thing’s a beast. And the Bayraktar, too. There’s that famous song about Bayraktars. It’d be nice to think: “Hey, that’s about me, too.”

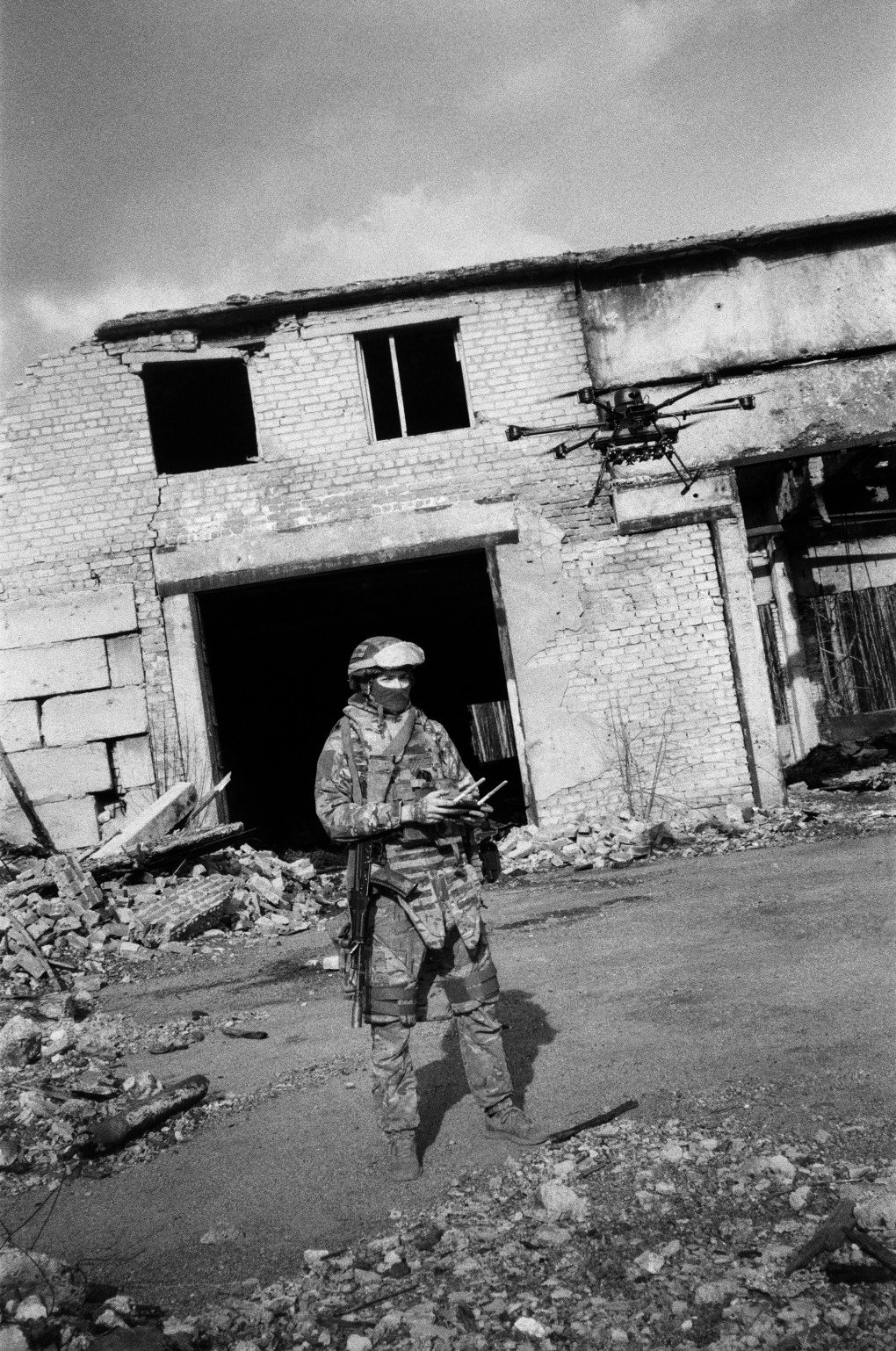

Phil, 22, and his Mavic and Matrice

Before Russia’s war, I’d been working as a cook since I was 14. In 2021, I decided to give the army a shot, and honestly, I liked it. After my mandatory service, I was planning to sign a contract with Azov.

Then, on February 24, 2022, the full-scale invasion began. I caught shards of window glass in my face. The Russians hit our command post with Iskanders.

Later, I transferred to the 3rd Assault Brigade when it was forming. At first, I served in artillery reconnaissance, then moved over to the drone systems battalion.

I’ve flown—or still fly—the Fury, FPVs, and pretty much every kind of Mavic and Matrice. I mostly do reconnaissance. Those drones aren’t super effective for dropping munitions, but to be honest, we give the Russians hell. Just with UAVs alone, we can completely shut down their assaults. I’ve had a bunch of cases where enemy infantry never even made it to our positions because we wiped them out before they got close.

If I had the chance, I’d happily take out Putin.

Phil

Ukraine’s 3rd Assault Brigade soldier

But the Russians have also advanced with drones. Just this morning, we had to relocate because our previous position was hit—it took 14 FPV strikes.

The scariest moment in all these years was during the Bakhmut campaign. The Russians must’ve spotted our position, but they missed at first. Their KAB hit the building next door, and three houses were just gone. We waited it out. I stepped out of the basement to grab a drone, and suddenly the ground exploded in front of me. My ears were ringing like crazy. A 120mm mortar had landed just 10–15 meters away. Luckily, the shrapnel missed.

My most successful mission was probably the assault on Kurdiumivka. We trapped an enemy group and spotted a column of four tanks and a BTR with infantry moving to support them. We passed the intel, and they were destroyed before they could engage.

Over time, the excitement over records or body counts fades. But if I had the chance, I’d happily take out Putin.

I don’t know what I’ll do after the war. I’m 23 now and have been in the army since I was 18. I guess I just want to live a peaceful life, without stress or memories of all this.

Koala, 32, and her “Targan” robot

Before the full-scale invasion, I ran a sushi bar and worked in SMM. When I joined the army, I knew I wanted to be in the 3rd Assault Brigade partly because I’d heard they had a unit working with ground robotic systems. I really wanted to work with drones and robots.

My system is called Targan. We use it to deliver supplies and ammunition to frontline positions. We work on request—someone needs something, we deliver it. If armored vehicles can’t reach a location, we send the robot. Sometimes we run more complex missions, like evacuating wounded or fallen soldiers.

We modify the drones ourselves. Developers often have one vision, but it doesn’t always match battlefield reality, so we make improvements based on what we’ve seen out there. Our unit has its own workshop that upgrades the robots. We’ve even completely rebuilt some machines from scratch into entirely new formats.

For example, when GRS platforms first started appearing, the assumption was that tracks were better than wheels. But after spending a winter in the field with these robots, it became clear that wheels are actually more effective. Winter brings moisture, mud, and snow that melts into slush—mobility is the biggest challenge.

If I could dream up the perfect ground robot, it would be one that could fully replace a soldier at the front, so no one has to die. But that’s unrealistic. Without infantry, we’re nothing. I honestly see us as the infantry’s support crew. Our job is to make sure they’re alive, healthy, and have everything they need. And I’m ready to work day and night to make sure of that.

-0666d38c3abb51dc66be9ab82b971e20.jpg)

-554f0711f15a880af68b2550a739eee4.jpg)

-206008aed5f329e86c52788e3e423f23.jpg)

-1afe8933c743567b9dae4cc5225a73cb.png)

-46f6afa2f66d31ff3df8ea1a8f5524ec.jpg)