- Category

- War in Ukraine

“I Became the Firework”: How a Canadian Fighter Survived a Russian Drone Strike on Canada Day

People from nearly every corner of the world have come to Ukraine to help. One of them is 23-year-old Canadian Mac Hughes. He arrived planning to stay a month, but the country and its people changed everything. First, he volunteered, then he fought. Now, even after being injured by a Russian Shahed drone, he’s still helping—and he has a message for the world.

“Before, the only thing I knew about Ukraine was that there was a ‘Chornobyl’ map in Call of Duty,” says Mac. “Then I found myself here—both in Ukraine and in a real Call of Duty.”

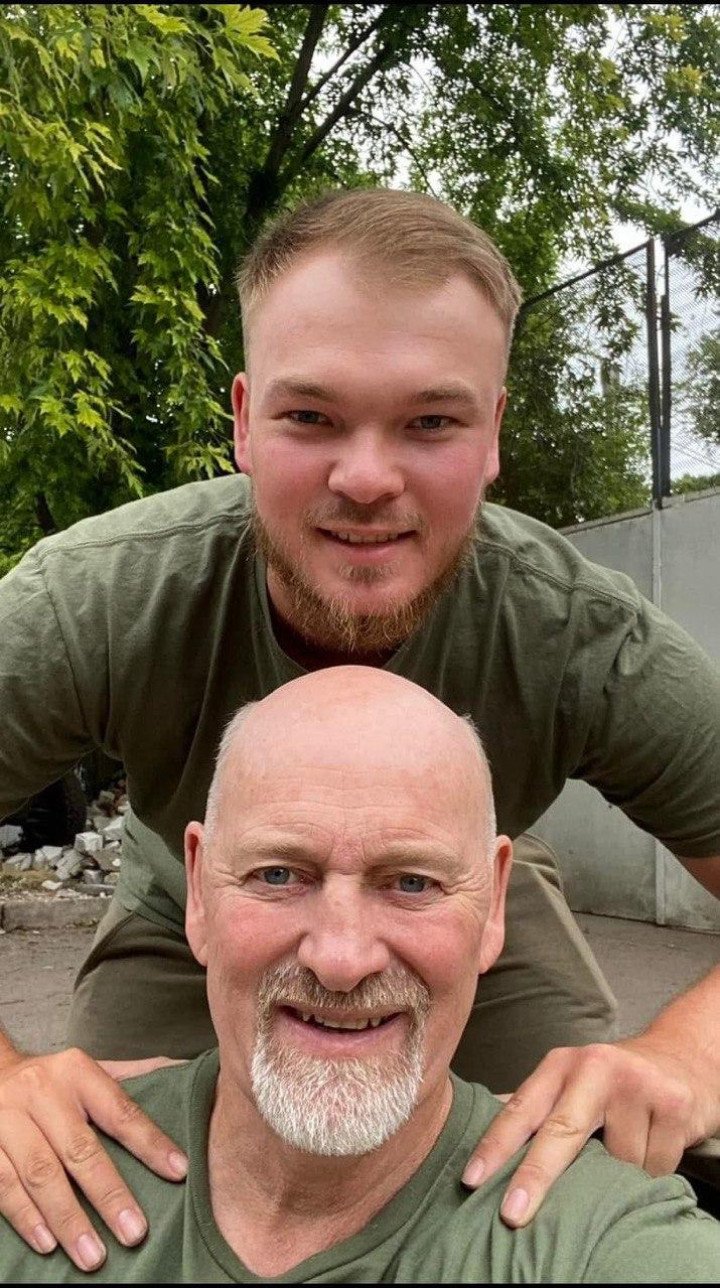

Mac Hughes, 23, is from Calgary, Canada. Just a few years ago, he couldn’t even imagine that one day he’d find himself at war on another continent. But after Russia’s full-scale invasion began, his father, Paul, immediately said he was going to Ukraine to volunteer. He was already at the front a week after the war started—an anonymous donor helped him buy a ticket. In August 2022, Mac decided to join him.

His first impressions were unexpected.

“I thought everything in Ukraine would be much scarier,” he says. “When I told people about my plans, everyone around me was literally shouting, ‘You’re going to war!’ So I imagined that the moment I stepped off the bus in Lviv, there would be bombs exploding, chaos, everything burning. But in reality, it was calm, because people were trying to live normal lives—especially in the western part of the country, farther from Russia. But when you go to front-line cities like Kharkiv or Kherson, of course, it’s different.”

A father and son’s mission

Although there are no completely safe places in Ukraine, in just one week at the end of October, Russians launched 1,200 attack drones, more than 1,360 guided bombs, and over 50 missiles of various types, President Volodymyr Zelenskyy said.

At first, Mac and his father volunteered in their recognizable minivan with a big maple-leaf flag. With the help of Canadian donors, father and son founded a Ukrainian NGO called H.U.G.S. (Helping Ukraine Grassroots Support).

“We did literally everything: delivered humanitarian aid, fed refugees, evacuated people and animals, helped clean houses after shelling, wove camouflage nets, repaired cars,” says Mac. “It was crazy but an incredibly interesting experience. It’s sad that war was the reason for it, but at the same time, I’m grateful I met so many amazing people and lived through such a wild experience. Most people just sit in front of the TV watching the news—but I’m here, in the middle of it all.”

Not all events were positive. Mac admits that many are ones he wishes he could forget — but can’t.

“In the Kherson region, we helped a group documenting war crimes,” he says. “One elderly woman told us that during the occupation, the Russians forced her grandson to dig trenches with his bare hands. It wasn’t dirt—it was concrete. Others told us how Russians came to a family, lined them up against a wall, and said: if you don’t bring vodka in 30 minutes, we’ll shoot him. In the Kharkiv region, after the deoccupation, I was in a torture chamber set up by Russians. Locals told me they filled people’s rectums with construction foam. I’ve seen and heard many horrifying things they did. And all of it stayed with me.”

Something else stayed with Mac for life—the tattoo on his arm, intertwining the Ukrainian and Canadian flags.

“That’s actually a funny story. I got the tattoo in a bar in Kharkiv—one of the few places back then where you could have a drink and talk,” says Mac. “Volunteers used to hang out there. While I was getting the tattoo, the bar owner was playing Linkin Park live, and I had a hookah, pizza, and beer in my hands—all at once. I don’t think anyone’s ever gotten a tattoo in such an atmosphere. A crazy but fun story.”

Later, the tattoo became almost a symbol of Ukrainian resilience for Mac, especially after he experienced the scariest moment of his life.

“I became the firework myself”

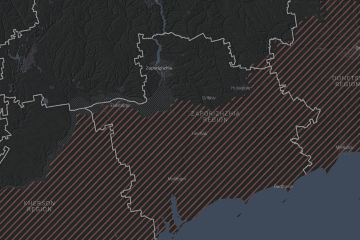

“It was July 1, 2025, in the Zaporizhzhia region,” he recalls. “Russian Shahed drone hit our shelter. I ran out to check if everyone was alive. Then the second Shahed hit—right where I was standing. I got trapped under a car. I didn’t think I’d survive. I screamed, called for my brothers-in-arms. I still can’t believe they heard me—one had ruptured eardrums, another had a concussion. My legs were burning when they pulled me out. A third of my body had second- and third-degree burns. Ironically, it happened on Canada Day. Usually on this date we launch fireworks—but that day, I became the firework myself.”

In the hospital, one of the first things Mac saw as the bandages came off was his Canada-Ukraine tattoo—untouched. “Ukraine always survives,” he said immediately.

The strike happened when Mac was no longer just a volunteer. One of his best friends, Sam Newey, was also in Ukraine—he had joined the Armed Forces as a volunteer.

“Sam was killed,” says Mac. “He always told me I should join the army, do more. After his death, those words stayed with me. It was the last straw. I hesitated for a long time—I liked volunteering, but deep inside I always wanted to join the army. His death became the moment when I decided—yes, I’m going.”

At the beginning of 2024, Mac went to serve in one of the brigades that included foreign units. During the war, he met other Canadians and even ended up in the same unit with a guy from his hometown, Calgary. The fighters were constantly moving: Zaporizhzhia region, Kharkiv region—“wherever we were needed, we ran,” Mac says.

How a city keeps its wounded from falling behind

After the injury, Mac couldn’t walk for 53 days.

“Most of my legs were badly burned, and after lying down for so long, when the skin heals, every movement stretches it—it’s painful. Taking my first steps again was incredible. But I still have problems with one leg—it doesn’t work properly. So I’m in rehabilitation now, already in my fifth hospital. I hope in a few months to get back to normal life.”

To raise funds for Mac, his friend Jay organized a fundraiser in his honor at a bar in Kyiv.

“I’ve been to events like that before, but when they did it for me—it was incredible. Really touching. The atmosphere was amazing—soldiers, civilians, everyone gathered, there was music, they sold souvenirs, signed posters, used RPG tubes—to collect some money for me. It helped me live in Kyiv, pay rent, support my father and my girlfriend.”

Mac himself didn’t stop being involved either.

“I’m in the hospital, but I try to talk to different organizations and volunteers,” he says. “We need to rebuild our unit—we lost everything: the car, weapons, gear, everything. But it’s hard for our team right now.”

-6c7b568bf1f65853b7afd9dc1c3ca1fe.jpeg)

Mac says that as a foreigner, he’s often asked what he’d like to tell people around the world about what he saw in Ukraine and what his message is.

“I always say one thing: go and help someone. Do something good. Don’t be a bystander — be part of history. Do something that will change someone’s life for the better. Do something that will change your own life for the better. Don’t just sit and watch as Ukraine gets bombed every day, as schools and parks are destroyed, as children and women die. This is reality. And if you can do something—do it. Do good.”

A new home

Now, while Mac is in rehabilitation, Ukrainian cities continue to suffer from Shahed attacks—the same kind that injured him.

“I heard those drones last night,” he says. “And this morning. For me, it’s probably the scariest sound in the world. When it approaches, it drowns out every other thought in your head. Then—an explosion, and that’s it. But I try to control myself. When I see videos of Shaheds online, I turn the sound on and listen, listen, until it stops scaring me. I have to get used to it.”

Mac has to listen to the Shaheds, just like all of Ukraine. And if Russia isn’t stopped, he’ll have to hear that terrible sound again and again.

“I told everyone I’d volunteer in Ukraine for a couple of months and then go back,” says Mac. “But everything changed. Now I don’t plan to return to Canada. I love Ukraine. Kharkiv is my favorite city—it even reminds me of Calgary. I see the problems, but I also see the incredible potential of this country. This is home.”

-29a1a43aba23f9bb779a1ac8b98d2121.jpeg)

-0666d38c3abb51dc66be9ab82b971e20.jpg)