- Category

- War in Ukraine

Why Americans Are Risking Their Lives to Fight Russia on the Ukrainian Frontlines?

-513811ca56e3ac81269697b10a3df64f.jpg)

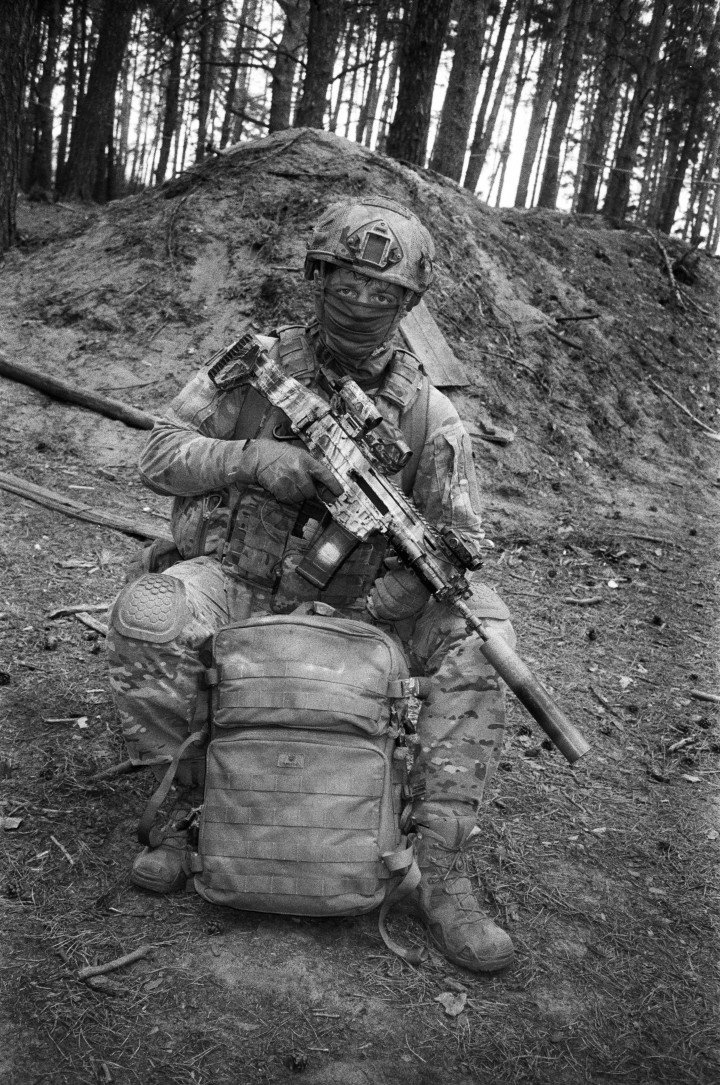

When Russia launched its full-scale invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, it shook the world. For many Americans, it was another headline — something happening “over there.” But for some of the US veterans and volunteers, it was a call to action. They packed bags, bought one-way tickets, and entered a war that wasn’t theirs, at least not by birth. For them, it became a matter of principle.

In exclusive interviews, we spoke with over a dozen American volunteers—Marines, medics, and veterans—now fighting on Ukraine’s front lines. We traveled close to the front to hear their stories firsthand: why they came, what they’ve endured, and why they keep going.

“I have the knowledge, I have the skills, and this is clearly a just cause,” says Ben, a 32-year-old former US Army medic from Wisconsin with six years of military service under his belt. “This is the first war of good versus evil since World War II.”

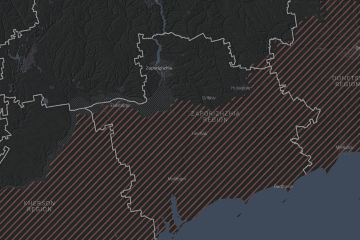

“I was working a terrible bar job in Texas, got fired, came to Kherson, and saw the Russians just bombing everything,” recalls Nick, a US veteran with Ukrainian roots. Nick has been defending Ukraine for the past three years, playing a key role in the liberation of the Kherson region and the Battle of Krynky. A former US Marine sergeant with ten years of service—including two tours in Afghanistan—he now serves in the reconnaissance platoon of Ukraine’s 39th Marine Brigade.

“I saw tank traps on children’s playgrounds,” he says. “That was it. I needed to be here.”

Their reasons are varied—family heritage, personal convictions, a sense of unfinished duty, or even a search for meaning after years of training in peacetime armies. But the decision is always personal.

Kahn, another veteran, describes hearing Zelenskyy’s call for foreign volunteers as something directed at him. A former sergeant with combat experience in Afghanistan, he felt the war was not only just, but familiar. “I’m half-Korean — my mother is Korean,” he says. “I couldn’t stop thinking about Korea, about how it ended. I didn’t want Ukraine to become another frozen conflict.”

The shock of reality

For many of these Americans, Ukraine shattered any remaining illusions about modern warfare. The reality of the front lines far surpassed anything they’d encountered before.

“This is a far more brutal war,” says Ace, a paratrooper and Iraq veteran from New Mexico. “I’ve been shot at. I’ve been under mortar fire. But nothing prepared me for this.”

Kahn thought his combat experience in Afghanistan would be more useful. “But right away I realized—this is a different war,” he says. “Different terrain, different enemy, different tactics.”

Nick recalls that during his service in Afghanistan, the Taliban didn’t really have artillery.

“They had a few mortars, but no real shells, and they weren’t very accurate, so we didn’t worry much about them. IEDs were a much bigger problem. But here? This is completely different.”

That sentiment echoes across every interview. These are not abstract battles on screens. They are trench assaults, drone swarms, and artillery barrages that last for hours. Ben, the former medic, describes being hunted by Russian drones while rescuing a wounded soldier.

"We ran out there—drones buzzing overhead, mortars landing around us. We dragged the guy back—it probably looked exactly like those famous old war photos. Explosions everywhere: bam, bam, bam. We got him into the bunker and started medical treatment. When we were done, he literally grabbed me and shouted, ‘Bratan!’—it’s like saying ‘bro’ in Ukrainian. You see? We didn’t even speak the same language. But we saved that guy, and now he’ll return to his family. It was also one of the most rewarding moments.”

Nick recounts how he fought the Russians almost face-to-face on one of the Dnipro River islands: “They came at us from maybe five to ten meters away. It was intense. Just thick brush, you can’t see the enemy—you feel them more than you see them. But none of them made it."

In another instance, Nick had a close call in a forest after a Russian counterattack: “They chased us for two kilometers. The Russians must’ve thought we were some badass snipers—we had long rifles and ghillie suits. Drones, artillery, everything they had. That day? I believed in God.”

The American fighters often speak of FPV drones—first-person view quadcopters, rigged with explosives—that have transformed the battlefield. One phrase keeps coming up: “modern war.”

In the US, Ukraine’s battlefield innovations have pushed the Pentagon to rethink its entire drone strategy: forming new units, launching the Artemis program, and partnering with Ukrainian manufacturers. The military is now adopting Ukraine’s fast, frontline-driven approach: rapid design cycles, modular tech.

Ace praises the level of training he received in Ukraine. Instructors emphasize hands-on knowledge, especially when it comes to drone warfare and the various types of mines used by Russian forces.

“It’s the first time I’ve had firsthand experience of what modern war really looks like,” says Ace. “And we’re still learning. The battlefield changes every six months.”

Things worth dying for

If brutality is the reality, values are the compass. These volunteers aren’t being paid much, and many fund their own gear. So why risk it all?

“This isn’t about square kilometers,” Nick says. “It’s about cultural identity. It’s about showing the world there are still things worth dying for.”

Kahn, whose heritage spans both America and Korea, draws historical parallels: “People talk about foreign fighters like it’s new. It’s not. Think of the Varangian Guard in the Byzantine Empire—the emperor’s elite guards, many of whom came from what is now Ukraine. Think of World War II when foreign volunteers joined the fight before their countries officially entered. This isn’t new. People have always fought for values greater than their flag.”

Uno, a 23-year-old American volunteer from Carlsbad, California, comes from a military family. He puts it more bluntly: “If you look at Russia’s demands, this isn’t just about Ukraine. They want to demilitarize Eastern Europe, dictate EU policy, and reshape the post-Cold War order. Ukraine just had the courage to say no.”

That courage, they say, is contagious. Uno has been defending Ukraine for the past year and a half. He now serves as an infantry assault platoon commander with the Azov Brigade.

“Kyiv—it’s like New York,” says Ben. “People here go to cafés, they dress well, they raise kids—under fire. They’re still trying to live. I’ve never seen that kind of spirit before.”

“If Russia is allowed to do this to Ukraine, then what’s to stop them from doing the same to others? I’m a paramedic. Saving people is my job,” says Omni Shine, a paramedic from New York. "Once I got here, I realized this isn’t just about democracy or the free world. Can I swear? The truth is, it’s so damn beautiful here—I don’t want to see this country go to shit, you know? All these peaceful people? They don’t deserve any of this.”

Brotherhood in the trenches

These men, many of whom had never set foot outside the United States before, have become part of a strange and profound fraternity. American, French, Argentine, Ukrainian—nationality blurs in the mud.

“We don’t even need to speak the same language,” says Ben. “We joke. We fight. We risk our lives for each other. That’s brotherhood.”

Ace reflects similarly: “We come from completely different parts of the world. But we train together. We bleed together. When we hit the battlefield, we’ll be covering each other’s backs.”

Even with limited gear, erratic logistics, and frozen funding, they admire their units: the International Legion, Azov, the 3rd Assault Brigade, Khartiia, and others. The training is serious. The discipline is real. And the will to fight—for each other and for Ukraine—is unshakable.

“I wouldn’t go to war alongside people I didn’t trust,” says Omni Shine. “And I trust these guys. Every single one.”

“A lot of guys come here without fully understanding what they’re stepping into,” says Uno. “But for me, I’m grateful—for the military training I’ve gained here, for the chance to immerse myself in Ukrainian culture, and to witness the resilience of this people. I’ve learned what humanity really means, what people are capable of doing for each other. I’ve learned a lot about who I am and what confidence and strength actually look like. It’s been worth it.”

Back in 2014, Ben had buddies who came here to train Ukrainians. Before he deployed, Ben reached out and asked them: “Hey man, I’m headed to Ukraine. What can you tell me about these guys?” And they said, “Bro, they’re wild. Like real cowboys.”

“And they were right,” says Ben.

What if Ukraine falls?

Most of these Americans don’t plan to stay forever. Some have families waiting. Others will return changed, with deeper convictions and sharper memories than they ever expected. But almost all are haunted by the indifference they see.

"I don’t see beauty in the chaos of war. The only positive here is that I’m helping,” Kahn says. "Even if my contribution is small, sometimes a single grain is enough to shift the balance. There’s beauty in that, but I wouldn’t say war should ever be glorified. There’s nothing beautiful about what’s happening here, because so many innocent lives are being lost. This war needs to end, and it must end on the best possible terms for Ukraine.”

“Back in the States, we live between two oceans. It’s easy to think war is far away. But it’s not. Peace is fragile. Complacency is dangerous.”

Kahn

“We made a promise to Ukraine,” says Ace. “We haven’t fully kept it. That’s why I came. Because I still can do something. The moment I arrived in Ukraine, I could immediately feel an overwhelming sense of gratitude and support from the Ukrainian people. Ever since I got here, I’ve received nothing but thanks, especially when people learn that I’m a foreigner.”

Ben remembers seeing the remnants of what Russia did in Afghanistan. Then, in Syria, “where groups like Wagner stood on the other side of the line from us,” he says.

For all their differences in background and motive, these American fighters agree on one thing: Ukraine’s struggle is not isolated, it is not optional, and it is not someone else’s problem.

“Will the world be a better place if Ukraine falls?” Ben asks. “That’s the question everyone needs to answer. Because if the answer is no, then we all need to act like it.”

“And to the Russians, I say: we’re coming,” says Omni.

-0666d38c3abb51dc66be9ab82b971e20.jpg)

-29a1a43aba23f9bb779a1ac8b98d2121.jpeg)

-35249c104385ca158fb62273fbd31476.jpg)

-554f0711f15a880af68b2550a739eee4.jpg)