- Category

- War in Ukraine

Ukraine’s Guerrilla Drone Warfare is Spurring a US Military Shift

Every Ukrainian frontline drone is piloted by someone whose expertise has evolved with the rise of FPVs and, by 2025, fiber-optic drones. Their battlefield insights are now shaping the behemoth that is the US defense industry. Can the Pentagon keep up with Ukrainian drone operators?

A Russian soldier lying in a muddy field tilts his head up, eyeing the camera. He is looking at a hovering Ukrainian drone, its bird’s-eye view drifting left to right. The soldier crosses his arms, indicating surrender. The drone drops water and a note, and then slowly leads the soldier out of the trench. Minutes later, Ukrainian soldiers take him in. He’s given medical care, then sent to a POW camp.

Three years into Russia’s full-scale war in Ukraine, drones have transformed into sophisticated tools with the potential to replace soldiers on the battlefield. As photographer Tyler Hicks told the New York Times, his 2022 shot of soldiers atop a tank in Bakhmut would be impossible today.

In fact, Ukraine built over 2.2 million FPV drones in 2024 alone and is, as of today, the top producer of FPV drones in the world. Ukrainian officials project that the number could rise to as much as 10 million annually, depending on resource availability. Ukraine was also the first to establish an entire branch, the Unmanned Systems Forces, dedicated solely to drone warfare.

How the US is catching up

Ukraine began modifying DJI Phantom 4 drones to drop F-1 grenades back in 2014, a tactic that gained prominence during the Russian invasion. Fast-forward to January 2025: the US formed its own Marine Corps Attack Drone Team (MCADT) citing “lessons learned from Ukraine.” American officers have since debriefed Ukrainian soldiers and studied their tactics to close the growing gap.

“We’ve got to learn how to use drones, how to fight with them, how to scale them, produce them, and employ them in our fights so we can see beyond line of sight,” said Colonel Donald Neal, commander of the US 2nd Cavalry Regiment.

In October 2024, the United States provided Ukraine with $800 million to help manufacture long-range drones, enabling the country to better counter Russian aggression using its own weapons. The success of Ukraine’s drone program has some thinking that America could recoup the billions spent, not with a minerals deal but in the form of battlefield knowledge and experience amassed during the war.

In March 2025, inspired by Ukraine, the US Defense Innovation Unit (DIU) awarded four contracts to four US companies to develop prototypes of long-range, single-use drones under the Artemis program. Two of these companies, Swan and Auterion, are collaborating with Ukrainian drone manufacturers.

“When I saw this award, I was like ‘Finally, we have real collaboration,’” said Kate Bondar, a Ukrainian fellow at the Wadhwani AI Center. Involving Ukrainian firms strengthens US-Ukrainian defense ties, with Bondar noting that the US industry’s past approach was a “huge misunderstanding” of the requirements.

“Developing more modular systems that accept different software and subsystems is much harder than it sounds, or the Department of Defense would have started doing it a long time ago,” adds Caitlin Lee, Director of the RAND Corporation’s Acquisition and Technology Policy Program. She warns that even with the Artemis program, structural challenges will remain.

The Artemis program will introduce a new class of weapons not currently available in the US arsenal. More importantly, where the US has traditionally imposed its own processes, this time it is directly emulating Ukraine’s approach to designing, building, and deploying drones.

What makes Ukraine’s model different is how closely its private sector works with the military. Instead of waiting for top-down orders, companies build alongside the troops. “[Ukrainian] feedback and iteration loops are incredibly fast,” says Artemis program manager Trent Emeneker.

The company commander of Ukraine’s 38th Marine Brigade UAV Battalion, callsign “Saint,” confirms this from the field.

“Some manufacturers adjusted their drones based on our needs,” he says. “That’s what good communication looks like.”

At the launch of Ukraine’s Brave1 Market in April, Vlad D, Chief Product Officer at a Ukrainian drone company, described his role as serving as a bridge between developments on the front line and the final product.

“You have to go there, talk in person,” he says. “We’re helping them, and they’re helping us. It’s mutual—a kind of synergy.”

How Ukraine became a leader in drone warfare

Ukrainian drone pilots' expertise is highly sought after globally, particularly as the US advances drone integration into its defense strategy. This knowledge also provides valuable insights for Ukrainian drone manufacturers.

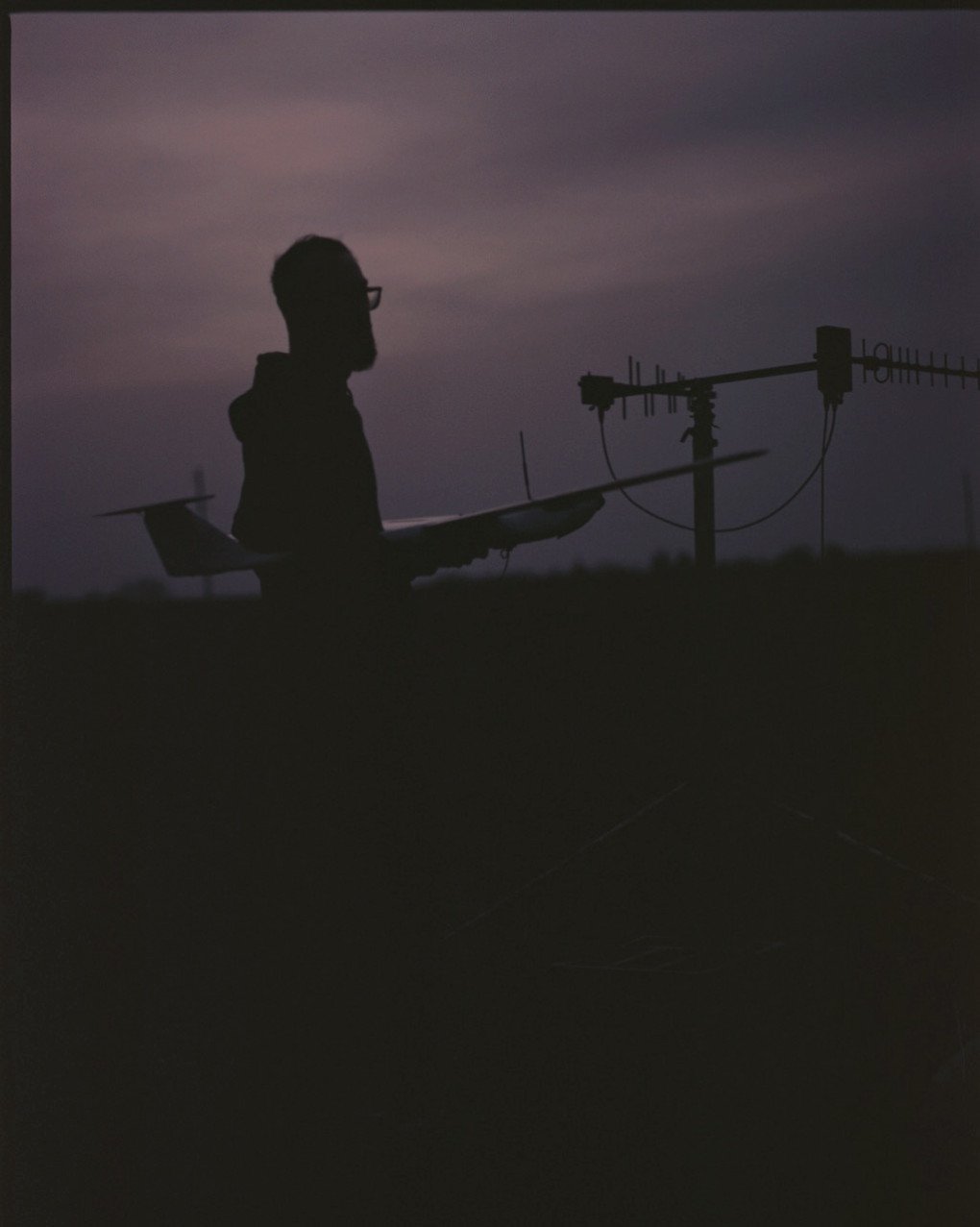

Saint, his hood up, soft-spoken, and wearing black-framed glasses, says his brigade has rapidly become a force through its innovative use of drone technology. Tongue in cheek, he describes his job as the best job in the world, “I get to play with toy planes,” Saint says from the driver’s seat.

Ukrainian drone pilots fly with distinct personal styles, visible even in combat footage. “When I send videos of my work, you can see right away it’s me flying because you see the way I approach the target,” says a soldier, callsign “White,” standing in the middle of an open field where Saint and he are training new recruits, dotted around the field flying practice drones.

White is 29 years old and one of the most skilled Ukrainian drone pilots in the 38th Brigade, standing out with his clean, short-cut hair, baseball cap, and glasses. “I always fly from the side,” he says. “To see the enemy and observe him before I make contact.”

“Experience plays a role 100%,” says White, who then brings up the concept of the master and student and defines his relationship with his commander: “I am his student; he taught me everything.”

When asked why Ukraine has been so successful at developing its drone warfare, White answers point blank, “Motivation. Motivation to kick them [the Russians] out.”

Learning through setbacks and iteration

Saint says electronic miscommunication is the leading cause of mission failure within his unit. Human error accounts for up to 20% of failures, often just a 2–3 meter miss, while technical issues like camera disconnections contribute around 30% of issues in his unit. Half the unit consists of new pilots, selected for aptitude and trained through 20–25 hours of simulator time and a week of field drills.

Despite these challenges, Ukraine has mastered the art of turning low-cost, commercially available drones into powerful long-range weapons, all while rapidly training new recruits. This ability to adapt and scale quickly has allowed Ukrainian forces to strike military targets deep inside Russian territory, often outperforming more expensive US unmanned aerial systems.

“They have figured out how to make adaptations and how to make the systems work under most conditions, even pretty extreme ones, and that is something [many] US companies just don’t have because we are not in the same environment right now,” Stacie Pettyjohn, the director of the defense Program at the Center for a New American Security told Air & Space Forces Magazine. “Ukraine is facing a real, living, breathing enemy that is constantly adapting.”

In light of Russia’s meatgrinder tactics and their huge mobilisation net, Ukraine faces a serious imbalance in manpower. Three years of fighting have thinned out the frontlines, so Ukraine has leaned into drones to preserve lives and extend reach.

“On the battlefield, I did not see a single Ukrainian soldier. Only drones,” a surrendered Russian soldier told the US-based think tank, Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS). “I saw them [Ukrainian soldiers] only when I surrendered. Only drones, and there are lots and lots of them. Guys, don’t come. It’s a drone war.”

Though human oversight continues to play a crucial role in decision-making during combat engagements, reflecting a human-in-the-loop approach, the CSIS came to the conclusion that “the Ukrainian military’s objective is to remove warfighters from direct combat and replace them with autonomous unmanned systems.”

DIY death from above

This evolution is evident in units like Paskuda Group, led by the FPV unit commander “Dolyna,” which specializes in using suicide drones to carry out operations, replacing traditional direct combat roles.

Dolyna attributes his unit’s success to better supply chains and individual initiative. Their commanders work hard to ensure the right components are delivered, and the unit shows strong dedication, with members often contributing up to half of their salary back to the group.

Prior to Russia’s full-scale invasion, Dolnya had no experience with drones whatsoever. He ran children’s summer camps and ultramarathons. “I wasn’t into video games or anything computer-related,” he says.

At the beginning of the war, Dolyna was a Javelin operator, though he felt frustrated by the ineffectiveness of his position, “I couldn’t strike enemy equipment, because it was hidden behind tree lines, or trenches, and to hit it with a Javelin system, you have to directly expose yourself to lock onto the target.”

While they were in their positions, Dolyna remembers being targeted by mortars of calibers up to 120 mm, artillery, and SPG systems . “We would get hit at our positions, and we couldn’t respond with anything; we just sat there,” he says. “It really wore me down.” In addition to feeling worn down, this led to a “strong desire for revenge, to strike back,” he says.

In 2022, Dolyna’s commander, callsign “Romakha,” introduced FPVs to the unit, an idea many superiors dismissed. “We had to prove it would work,” says Dolyna. Their first successful mission came near Bakhmut.

“We were stationed with anti-tank equipment, and we decided to improvise; we made our first explosive device ourselves,” says Dolyna. They took a can from an energy drink, cut off the top, inserted a small tube, secured it with two-component adhesive, and filled it with shrapnel. The team had previously spotted a Russian machine gunner taking cover and decided to fly the weaponized drone toward him. “We flew directly to the position,” says Dolyna. “After some time, it became quiet.”

Active warfare enables soldiers to innovate, and depending on their commanders, the weapons improvised can be seen on the battlefield within days. “It’s not that the commander orders you to try something,” explains Dolyna. “You come up with an idea yourself and can implement it.”

“You have to live inside this work to understand it.”

“Dolyna”

Commander of the FPV Unit Paskuda Group.

Dolyna believes drones emerged from Ukraine’s lack of proper resources at the beginning of Russia’s full-scale invasion. “When we get our salary, we each pitch in some money, place an order, assemble it, and test it in the field. Once it’s tested successfully, we try it in combat conditions” he says.

Dolnya confirms Paskuda group currently targets Russian supply routes 30 to 40 kilometers behind the front line.

The experience and data gained by the Paskuda Group are only shared with other military units, unlike the 38th Brigade drone unit, which does have a back-and-forth with the private sector. In Dolyna’s opinion, “Civilian companies are mostly interested in making money; they take what we develop and try to sell it back to us. I’m not interested in that.”

Village drone labs

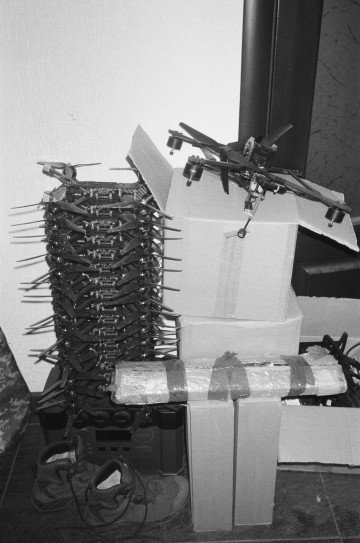

Behind the closed doors of a Ukrainian village home, complex workstations are filled with colorful cords, 3D printers, tools, fiber optic cables, propellers, and shelves stocked with half-built FPV drones.

Kostiantyn and Anton, drone engineers and identical twins, burst out of the workshop heaped with energy, talking fast and finishing each other’s sentences. If you’ve seen the twins in Ocean’s Eleven, you get the vibe.

Kostiantyn, who used to be in the infantry and served during the now-infamous Battle of Krynky, fought from October 2023 to June 2024. Behind him, a 3D printer whirrs. Kostiantyn holds a tiny Scythian arrowhead in the palm of his hand, freshly printed. They attach the arrowheads to all the suicide drones that the pilots fly out.

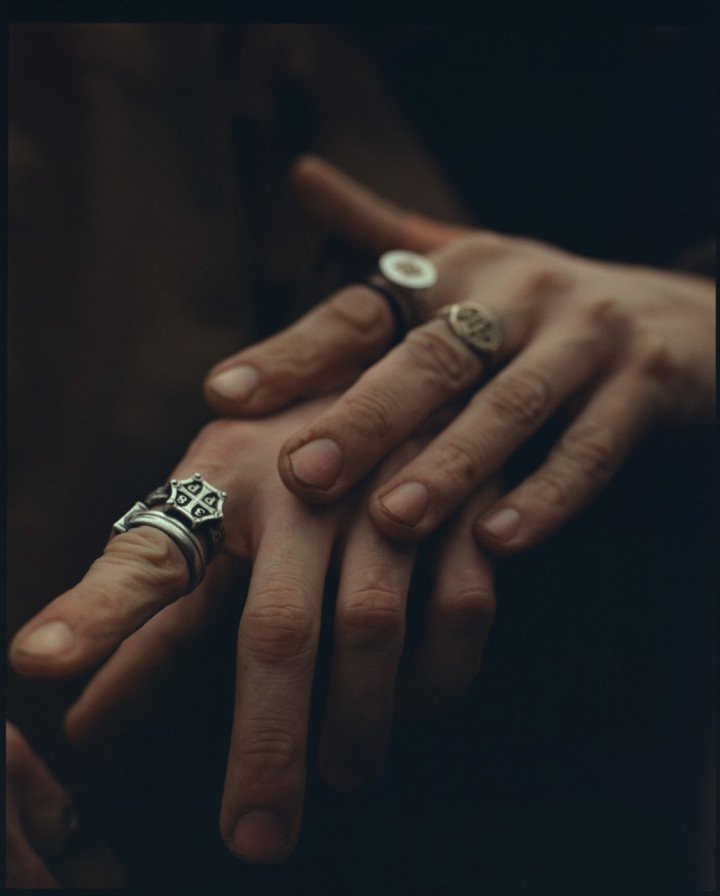

Both Kostiantyn and Anton were jewellers before the war. Kostiantyn also draws and paints, transforming the often traumatic scenes he witnessed into bulging, vibrating drawings. He talks about warfare like an artist, which he believes are people who belong in the military.

“People who want to do art have to join the military,” he says. “How do you want to reflect reality if you haven’t been a part of this? If a person has visual experience, it helps with designing stuff for drones.”

Unique to the war in Ukraine, civilians from all walks of life often find themselves completing military roles, from engineering to logistics. While traditional armies are typically composed mostly of career soldiers, Ukraine’s war effort has drawn the likes of jewelers, fishermen, and road engineers into its ranks due to voluntary and involuntary mobilisation. This diverse expertise has fueled the country’s innovative, non-conformist drone industry.

“In some sense, this can be interpreted as a great strength in the evolution of drone technology, as many kinds of intelligence and life experience converge around one technological thing,” says Saint.

From drone-on-drone warfare to fiber-optics

Later in the day, Saint stops the car outside a bombed-out building recently hit by a Russian ballistic missile. Small shops have restarted operations, selling dried fish, eggs, and chips.

Standing nearby is another soldier in the 38th Brigade, callsign “Hrusha,” who used to work in road construction. Around 40 years old, he stands outside the building, his hand resting on the strap of his backpack. Hrusha is from Pokrovsk, a city some describe as uninhabitable due to intense drone warfare. His track record—46 confirmed drone-on-drone kills—far surpasses the average of five per operator.

Hrusha and his team were among the first to start shooting down reconnaissance drones like the Russian ZALA KUB drone. Hrusha attributes his expertise to an unusual source: fishing. “It’s all about catching,” he explains. Years of casting lines have honed his instincts—now redirected toward drone piloting, where precision is key.

The evolution of drone-on-drone warfare has dramatically altered the aerial landscape over Ukraine, presenting a real challenge to Russian forces. “They’re Russia’s eyes,” Hrusha says. “And we need to blind them.”

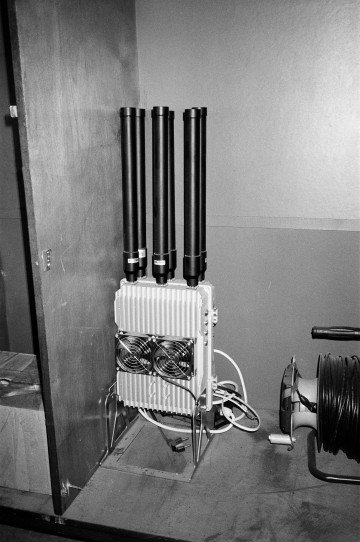

Though the real “blinding” tactic is Electronic Warfare (EW), which has become a pivotal component of the war against Ukraine. Both sides deploy cutting-edge technologies that disrupt communications, navigation, and radar systems.

In contrast, the US military’s EW skills have not kept up with the current climate. “The Joint Force has lost some muscle memory defending against electromagnetic attack,” said Lieutenant General Dan Caine, the US Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff. He described the US’s current EW readiness as having “atrophied,” with investments failing to keep pace with evolving threats.

Recognizing the gap, the US launched its Transforming in Contact initiative, which integrates “lessons from Ukraine,” as General Christopher Cavoli, head of US-European Command, said. The initiative integrates emerging technologies, particularly in areas like EW, into active US units.

The battlefield continues to evolve, with traditional jamming becoming less effective and fiber optics emerging as the new solution.

Both Dolnya and Saint say Russia is leading the charge in this domain. Unlike conventional drones, fiber-optic drones are tethered to thin wires that can go up to 30km, making them unjammable. The only reliable way to take them down is by locating and killing the operator.

Nobody really knows where this development will lead, but one thing is sure: “Ukraine has become a lab for what the future of warfare across the planet will look like, " said Andrew Schwartz, CSIS’s Chief Communications Officer.

-554f0711f15a880af68b2550a739eee4.jpg)

-206008aed5f329e86c52788e3e423f23.jpg)

-1afe8933c743567b9dae4cc5225a73cb.png)

-46f6afa2f66d31ff3df8ea1a8f5524ec.jpg)