- Category

- War in Ukraine

Inside Kostiantynivka, a Ukrainian City Living in a Killzone

As Russia closes in on Ukraine’s frontline city of Kostiantynivka, a key gateway to Kramatorsk, we witnessed firsthand how Russian troops are methodically razing it, preparing the ground for their next urban battlefield.

The road leading to Kostiantynivka is deserted. Every other house on the way is in shambles. Our silver car stands out like a sore thumb in this silent post-apocalyptic landscape.

We stop at a checkpoint. Anti-drone nets entirely cover it.

Our camera operator and driver Ivan sticks his head out of the window. “Is it dangerous to drive here?”

The officer returns our documents to us and shrugs. “Well, drones are flying.”

Approaching the killzone

The open road is in front of us. We need to drive fast, with the windows open, and be on alert before reaching Kostiantynivka’s outskirts, which have become a kill zone over the past few months.

“I was almost hit by artillery there,” Yevhen, the press officer from the 28th Brigade, says.

His brigade, among a few others, has been relocated from nearby Toretsk—a town entirely razed to the ground—to defend Kostiantynivka, a key Ukrainian-controlled stronghold located on the way to Kramatorsk—a crucial transportation hub and the gateway to the eastern Donetsk region.

And the Russians are advancing. Slowly, but relentlessly, Yevhen tells us.

“If they take this hill,” he says, pointing in the direction of Chasiv Yar, behind the horizon line where a thick plume of smoke rises in the sky, “they’ll have control over this road, and they’ll try to cut our logistics.”

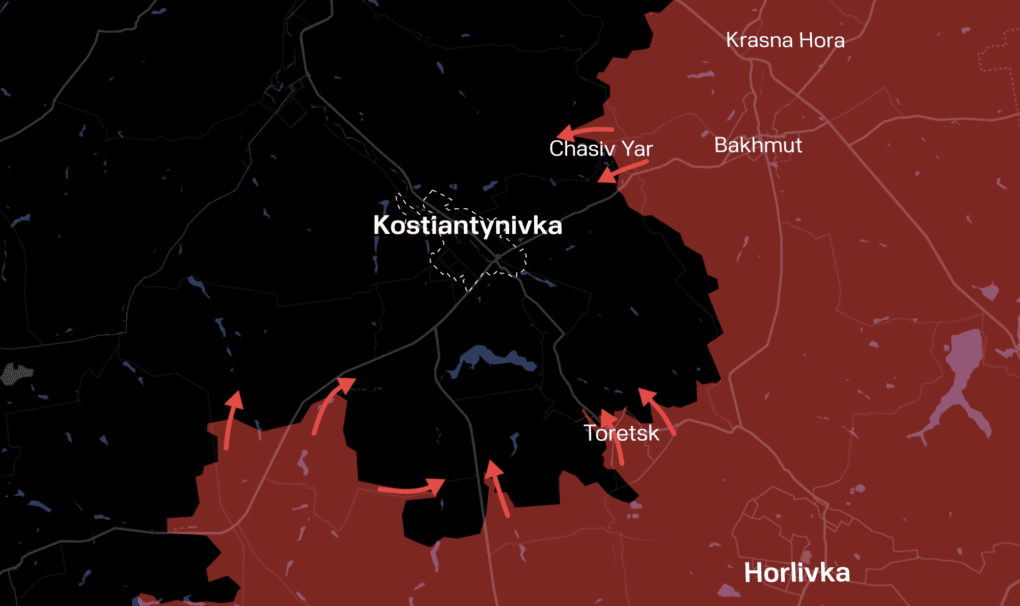

The Russians are attempting to capture the city in a pincer movement from Chasiv Yar in the northeast direction, Toretsk and Niu-York in the southeast, and Novoolenivka from the southwest, using a proven method of a meat grinder assault and relentless pounding.

They’re around five to six kilometers around the city, but “it doesn’t matter,” Yevhen says.

The Russians are using “Molniya” drones that look like cardboard planes and carry more than 10 kilos of explosive charges. The other threat that has plagued Ukrainian skies over the battlefield is fiber optic drones, impossible to detect and jam with electronic warfare systems.

“They use them in ambush tactics, like putting it on the road, waiting until a car passes by, and attacking it,” says Yevhen. “Now the gray zone is basically not the land between our zero line and their zero line, but ten kilometers behind us and ten kilometers behind them because of the drones. You can get killed anywhere.”

The last life in Kostiantynivka

Once inside the city, it is best to avoid certain areas—they are now in ruins, and there is nothing left to hide our car under.

“I could bring you to some hot spots, but that’s the last thing you’ll see,” Yevhen laughs. “I mean, I can jump out of the car, I’m used to it—but you guys might burn inside before you know it.”

Case in point, a couple of weeks ago, a Molniya drone killed a taxi driver and a passerby in the middle of the street, in broad daylight.

The burned car is still in the middle of the city, like an ominous warning for passersby to avoid being in the open and stay on the move.

While conducting the interview, we hear at least two drones flying over us. Bursts of anti-aircraft gunfire erupt sporadically, first far from us, and closer as the deadly buzzing sound gets closer. Two or three gliding bombs land nearby —all in the span of a half-hour.

Yet, people continue to run their errands between 11 a.m. and 3 p.m. before the curfew starts, transforming the city into a ghost town.

During this short daily timeframe, administrative services continue to operate, young people walk down the main street, and pensioners go about their daily tasks, despite the constant background noise of shelling.

Most shops have wood panels on their shattered windows, and most residential buildings bear the familiar stigmas of war.

Some are burned to the ground, some are eviscerated in two, showing the remnants of some bedroom cut in two, where the only thing that resisted the shock is a dated Soviet wallpaper.

Out of 67,000 people, only 6,000-7,000 are still here, struggling with the constant threat of Russia’s gliding bombs and drones. Nobody flinches anymore, accepting a potential death coming from the sky as yet another part of daily life when the Russians approach.

The lack of drinking water brings everyone together at the same spot to fill massive bottles of water and discuss the latest news. The omnipresence of war has replaced daily gossip.

Valentyna, an elegant woman in her late 60s, can’t help but punctuate her sentence with a copious amount of swear words that would make a soldier blush. Like many locals, she’s stuck here because her meager monthly $100 (4000 UAH) pension doesn’t allow her to live anywhere else.

“How the fuck am I supposed to pay for a damn 11 000 Hr ($260) rent in Kyiv? And the bills?” she says.

“Often people come back because they left for another region, ran out of money, and are returning to Kostiantynivka,” Stanyslav, a first responder, later explains. “But if their houses are destroyed, then they will leave completely.”

Most people don’t want to talk to reporters. Or rather, they hate us. For the locals, our black gear makes us birds of ill omen because they think that every time journalists gather somewhere, the Russians will automatically strike the place.

For them, we’re responsible for Russia’s strikes.

“Turn the fucking camera off,” a man tells us, before adding, in a calmer tone: “You want to see the real life here? Drop your black safety gear, come to my place, you’ll sleep there, no problem—but no one will talk to you dressed like that.”

This is part of Russia’s insidious victory over the locals’ minds. After three years of relentless attacks, the residents are slowly shifting to blame the Ukrainian military and the journalist for their ordeal.

Ukrainian soldiers end up fighting for a population that blames them for their misfortune, creating a deeper divide between two worlds that barely coexist in a city where life increasingly resembles a train wreck in slow motion.

Kostiantynivka’s unflinching first responders

Meanwhile, first responders from the emergency services are always here, keeping a watchful eye for each attack, each local to save, each body to dig out from the rubble of the next attack with a selfless devotion, knowing full well they’re the Russians’ double tap target of choice.

Their map is dotted with the locations of the latest attacks. Every street corner has its own little dot, making the plan look like it’s infected with smallpox.

“When they approach the area close enough, they begin to use both FPV drones and artillery, and they work with KABs and FABs from a distance,” Stanyslav, a first responder, tells us. “If they get even closer, they also use mortars.”

Stanyslav has been through hell and back. Originally from Bakhmut, nothing fazes the quiet, tall rescuer with a pensive look, even when we hear the sound of drones nearby.

“Better go, because we never know,” he says, pointing at the horizon. “Only a couple of kilometers from there, you’ll meet our friendly neighbors. Better go back down this road.”

A quick hurt flashes over his face when we stop at a supermarket, blown up by a Russian rocket months ago.

“Ten people died here, including some children,” he says, staring blankly into the void. “Not counting the wounded. There were more than three dozen wounded here.”

Another turn on the road, another gutted building. Russia’s glide bomb fell a couple of days before.

Some neighbors try to clean the rubble by hand, piece by piece, to try and bring back a semblance of normality in this hellish landscape.

Ivan, an elderly man with his winter hat pulled low on his head and a tremor in his hand, asks for a cigarette.

“I’m the only one left from all the residents of this building,” he says, violently shaking. “Everybody left the second floor. If you saw the way I looked… My face was covered in blood; I had cuts everywhere. The shockwave pushed me against the wall.”

Ivan turns to the remnants of his previous life and stares.

“Where should I go? I have nowhere to go.”

-0666d38c3abb51dc66be9ab82b971e20.jpg)

-554f0711f15a880af68b2550a739eee4.jpg)

-206008aed5f329e86c52788e3e423f23.jpg)

-1afe8933c743567b9dae4cc5225a73cb.png)

-46f6afa2f66d31ff3df8ea1a8f5524ec.jpg)