- Category

- War in Ukraine

Russian Courts Prosecute Journalists as Terrorists to Bar Them From Prisoner Swaps

“The cell is cold, rats run around, the light is on constantly.” This is how a civilian journalist abducted in Russian-occupied Melitopol describes her detention. Like many other Ukrainian media workers, Yana has been reclassified by Russia as a “terrorist” and sentenced in a closed, staged trial, effectively erased from public view and from prisoner-exchange talks.

Journalists have become the “perfect candidates” for Russian authorities to falsely accuse of “terrorism,” therefore pushing them out of prisoner-exchange discussions.

When Russia labels Ukrainian journalists as “terrorists,” it fundamentally changes how they are treated and their chances of release. Russian courts have increasingly used terrorism-related statutes to prosecute Ukrainian civilians, essentially criminalizing dissent and everyday resistance by creating a chilling effect on other citizens in the temporarily occupied territories of Ukraine.

By 2025, Russian authorities had completed the fabrication of criminal cases against journalists from RIA-Pivden , formerly RIA-Melitopol, a local online outlet founded in Melitopol and forced to relocate to Zaporizhzhia after Russia’s full-scale invasion. Russian courts sentenced the journalists to 14–16 years in prison on terrorism charges. The sole exception has been the release of the outlet’s Telegram channel administrator, Mark Kaliush, whose testimony confirmed the routine use of torture in Russian detention, UNITED24 Media sources say.

This pattern extends far beyond a single newsroom, and the true number of civilians held by Russia is unknown. Ukrainian officials estimate it runs into the tens of thousands, with many cases deliberately concealed.

“We cannot know the real number because Russia is hiding it,” said Igor Kotelianets, head of the civic organization Association of the Relatives of Kremlin Political Prisoners. “The Russians know they are committing war crimes, and they fear accountability. What we know today is that at least tens of thousands of civilians are being illegally held by Russia.”

This article focuses on journalists and media workers from Melitopol in Ukraine’s Zaporizhzhia region, where Russia’s abductions of media workers have been among the highest in the occupied territories. Many were subjected to sham trials and remain in Russian captivity.

Torture and forced labor

Yevhen Ilchenko, a lawyer and civic journalist, stayed in temporarily occupied Melitopol in 2022 to document life under Russian control. Through his news Telegram channel, “Milyi Topol,” he reported on abuses, war crimes, and collaboration by local officials. That decision cost him his freedom.

On July 10, 2022, Ilchenko was seized outside his apartment while taking out the trash. Witnesses reported that several vehicles arrived, one bearing the “Z” symbol used by Russian forces. Masked men in black uniforms forced him into a car and later raided his apartment, locking his wife and daughter in a room while seizing phones, computer equipment, documents, and personal belongings.

For weeks, Ilchenko was held in undisclosed locations, including detention facilities and basements used by Russian forces. During this period, he was subjected to mock executions to force a confession, and taken naked into the forest at night to simulate executions and then returned to prison, according to human rights defenders citing Ilchenko’s messages. Russian authorities later aired a staged video portraying him as a “terrorist,” visibly exhausted and gray-haired after weeks of abuse.

The repression escalated. From September to December 2022, Ilchenko was forced into labor near the front line in the Zaporizhzhia region, digging trenches, cleaning weapons, and building fortifications for the occupying forces. Reporters Without Borders verified photographs he managed to send from the site, calling the case unprecedented. “Captured, tortured, and then enslaved,” the organization said, describing it as forced participation in the war effort.

In December, Ilchenko was returned to prison and transferred to Taganrog Detention Center №2 in Russia, where former detainees reported being kept under constant lighting that prevents sleep, and held in overcrowded, unsanitary cells.

Reporters Without Borders has described Ilchenko’s case as the first documented instance in nearly 40 years in which a journalist was captured, tortured, and then subjected to forced labor amounting to slavery, calling for his immediate release.

Sham trials

Other journalists from Melitopol face similar fates. Vladyslav Gershon, who was one of the administrators of the Telegram chat “Melitopol is Ukraine,” was sentenced to 15 years in prison. The charges included participation in a “terrorist organization.”

Heorhii Levchenko, who worked with the Ukrainian RIA-Pivden newsroom for more than a decade, received a 16-year sentence. Charges? Participation in a “terrorist organization.”

Yana Suvorova, an administrator of the Telegram channel “Melitopol is Ukraine,” was just 18 when Russian forces came for her. Before the invasion, she lived an ordinary life, worked in the beauty industry, and planned to continue her studies. After a closed hearing, she was sentenced to 14 years in a penal colony. Charges? “Aiding terrorist activity” and “high treason.” The details of her case remain classified.

“The cell is cold, rats run around often, and the light is on, constantly,” Suvorova’s boyfriend said about the conditions of detention. “After it became clear that Yana would be transferred to Donetsk and that a verdict would be issued, her state deteriorated greatly. The stay in Donetsk was particularly difficult: she was among girls who had already attempted suicide, and this psychological pressure affected her. Perhaps it was a deliberate method of pressure to force her to cooperate, but it is difficult to say for sure.”

Incommunicado detention

Another journalist, Anastasiia Hlukhivska, remains held incommunicado . Russian authorities refuse to acknowledge her detention, leaving her family without information about her whereabouts or condition.

“She would come into the cell, lie down, and remain silent the entire time,” a former captive told the RIA-Pivden team in 2024. “One of the guards even asked me to keep an eye on Nastia, to see how she was doing”. She was interrogated with electric shocks when she asked for her heart medication, which is usually needed by those subjected to electric torture.

Additional reports indicate that Anastasiia might be held in the Kizel SIZO, Perm Krai, Russia, a facility notorious for the abuse of detainees, where Ukrainian journalist Viktoriia Roshchyna and Ukrainian mayor of Dniprorudne, Yevhen Matveiev, were tortured to death.

“I call it Dimland”

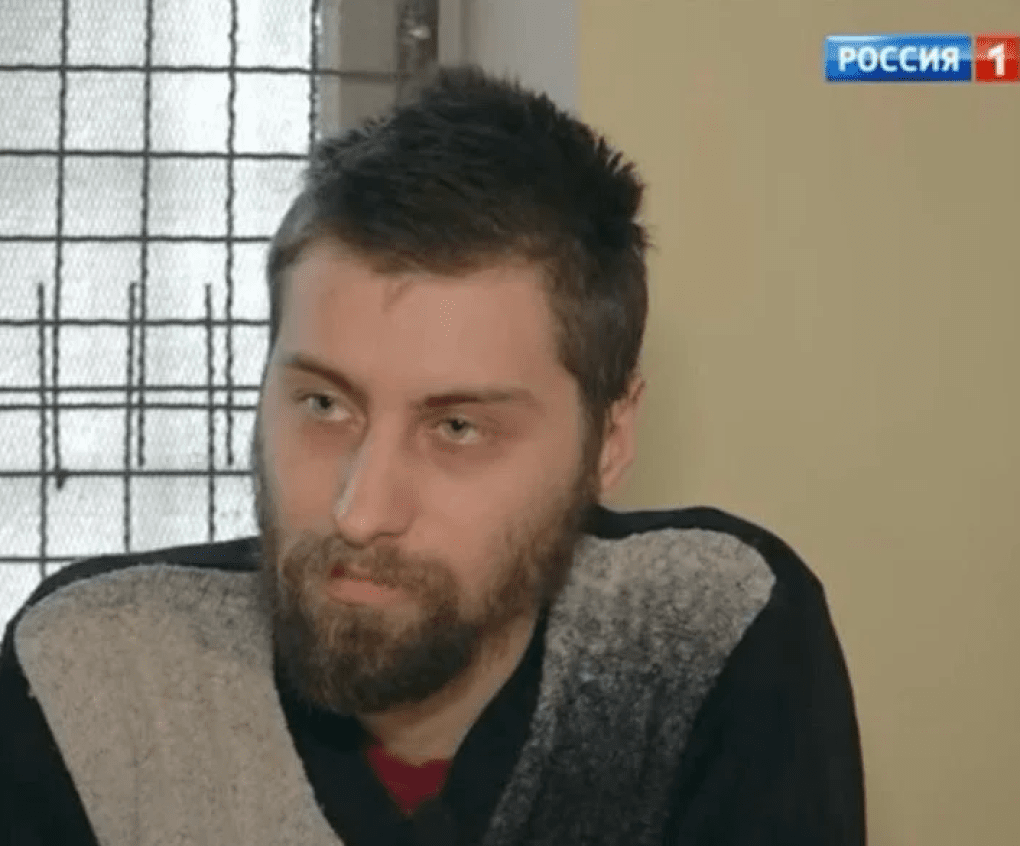

Kostiantyn Zinovkin, an engineer by training, was preparing to open his workshop, was abducted in May 2023 after being seized by masked men. His mother was initially told he had violated curfew. He was later charged with high treason and terrorism-related offenses, accusations human rights groups say are routinely fabricated.

In letters from detention, he describes a world of suffocating monotony: “I call it Dimland. Why? Because the brightest thing there is dreams. Everything around is in faded shades of green-yellow-brown.”

His wife, Liusiena Zinovkina, has since become an advocate not only for her husband but for all unlawfully detained civilians.

“We need to fight not just for Kostiantyn’s release,” she said in an interview with Hromadske Radio. “But for the entire category of illegally imprisoned civilians. Until May 2023, I did not fully grasp how catastrophic the situation for civilians really is. It is obvious that if I fight only for Kostia, it will lead nowhere.”

Terrorism charges as a tool to silence Ukrainian journalists

Since Russia’s occupation of Crimea in 2014, its authorities have increasingly relied on counterterrorism laws to justify the arrest, interrogation, and long-term imprisonment of Ukrainians from occupied territories. Such actions help the Kremlin reclassify civilians and prisoners of war protected under international law as “terrorists,” stripping them of legal safeguards and enabling harsh punishment.

After Russia’s full-scale invasion in 2022, this practice sharply escalated. Anti-terrorism statutes have been used to legitimize arbitrary detentions, forced transfers, and politically motivated prosecutions in occupied Ukrainian regions. Human rights groups describe the scale as unprecedented, with terrorism and extremism cases against Ukrainians surging by nearly 5,000 between 2022 and 2024.

“Today, Vladimir Putin is one of the world’s leading jailers of journalists, with 50 media professionals imprisoned by Russia,” said Pauline Maufrais, RSF Regional Officer for Ukraine. “Ukrainians are at the forefront of this repression: 29 are detained, some for nearly a decade, often held thousands of kilometres from their families and subjected to inhumane treatment.”

Long overdue international action

As peace negotiations continue, civilian prisoners remain trapped in a legal void. While the Geneva Conventions require the exchange of military personnel, no mechanism exists for civilians, even though international law explicitly forbids their detention in the first place

“As for civilians, according to international humanitarian law, we cannot exchange them. It is expressly forbidden,” Ukrainian Ombudsman, Dmytro Lubinets, said in a commentary to NV. “Secondly, we see that the Russians also violate the Geneva Conventions, which explicitly state that they have no right to take civilian prisoners in the first place. They do it anyway.”

As long as Russia continues to prosecute civilians and journalists in particular as “terrorists,” they remain trapped outside the laws meant to protect them and beyond the negotiations meant to bring people home. Without a dedicated mechanism for the return of civilian detainees, their cases risk becoming permanent, leaving journalists to serve decades-long sentences not for crimes committed, but for refusing to disappear.

A mechanism for returning civilians will not appear on its own. But if we continue to appeal to the European community, people with the authority and capacity to design such a mechanism will emerge and begin to put it into practice.

Liusiena Zinovkina

Zinovkin’s wife

-f88628fa403b11af0b72ec7b062ce954.jpeg)

-605be766de04ba3d21b67fb76a76786a.jpg)

-0c8b60607d90d50391d4ca580d823e18.png)

-29a1a43aba23f9bb779a1ac8b98d2121.jpeg)