- Category

- War in Ukraine

The “Gentleman’s Kit” of Torture: Firsthand Accounts Reveal Russia’s Brutal POW Abuse System

Suffocation with plastic bags, breaking fingers, electric shocks to the genitals, and forced self-mutilations of pro-Ukrainian tattoos are only a small part of what Russia imposes on Ukrainian POWs and captured civilians. The Memorial Human Rights Defence Centre released a report uncovering these systematic atrocities.

This article contains graphic descriptions of torture, sexual violence, and other forms of abuse suffered by Ukrainian prisoners of war and civilian detainees in Russian custody. Reader discretion is strongly advised.

Almost all Ukrainians who returned from Russian captivity report undergoing torture, humiliation, and the lack of medical care in the detention centres.

The organization’s monitoring mission visited Ukraine from January 17 to 30, 2025, to collect information on human rights violations and violations of international humanitarian law, including war crimes that were committed after Russia’s large-scale invasion. The mission visited Kyiv and the Kyiv, Kharkiv, Poltava, Mykolaiv, Kherson, Odesa, and Chernihiv regions.

The human rights activists conducted 40 interviews with Ukrainians who were directly affected by the actions of Russian military and government officials, including those illegally detained in the temporarily occupied territories, released prisoners of war, witnesses, and family members of victims.

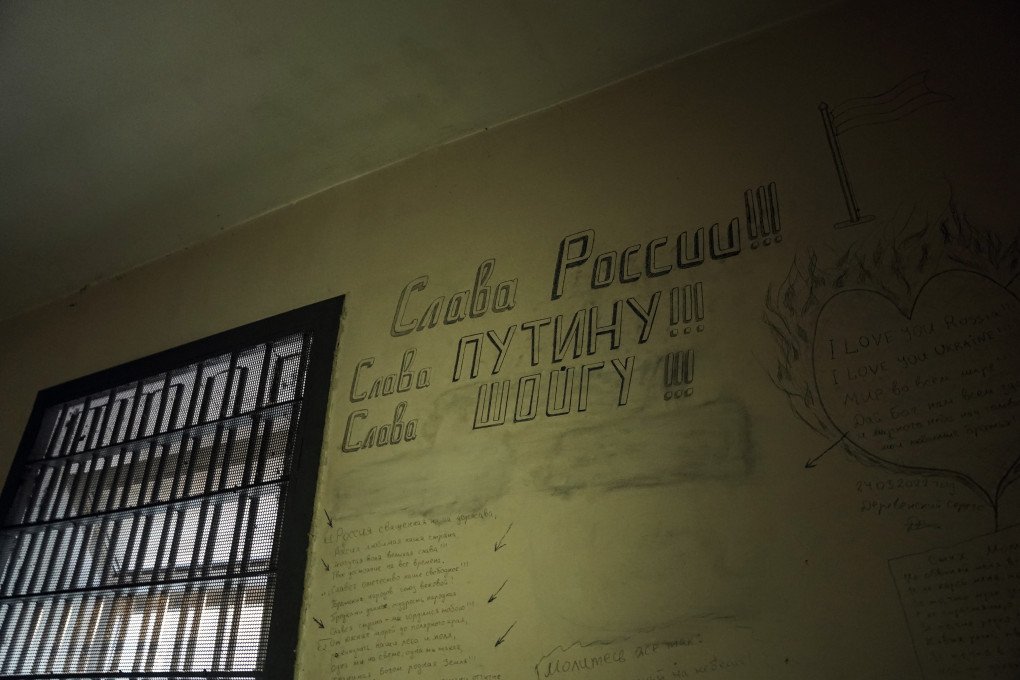

Russian authorities hold Ukrainians in colonies and prisons that were tested for decades, the report says. Here are some of the detention centers supported by commentary from freed Ukrainian POWs.

Former Penal Colony №120, Olenivka, Donetsk region, Ukraine

Two Ukrainian Marines from the 36th Marine Infantry Brigade, AA (junior sergeant, captured April 2022) and BB (contract soldier, captured at Azovstal in May 2022) shared their time spent at the Correctional Colony №120 in Olenivka, where Russian forces took them by bus after capturing them.

The colony, which had been previously closed, was hastily reopened and ill-prepared: windows lacked glass, toilets had been ripped out, and there was no water or heating. Initially, prisoners slept on the bare concrete floor. Although mattresses were later issued, there was still not enough space, forcing men to sleep in shifts and occupy all available areas, including corridors.

Upon arrival, both soldiers experienced the “corridor of honor"—a punishment where the Russian prison staff lined up and beat the running prisoners with belts, boots, and rubber sticks. Some would fall immediately, but the beating would not stop. Those would be then dragged to the wall and forced into a stress position (“starfish,” hands above head) while masked men continued the assault with sticks.

Food and water

Meals were provided three times a day: in the morning, POWs were given tea or boiling water and a piece of bread; at lunch, they were given tea and a quarter of a loaf of bread and half a plate of pearl barley or sauerkraut; for dinner, tea and a piece of bread. Russian guards would give only two to three minutes to eat. Taking food away or even chewing on the go was forbidden under threat of severe beatings or being forced to sing Russian songs while squatting. One witness reported that 80 men ate from a single bowl at one point.

The biggest problem was the scarcity of drinking water, which was brought in by fire trucks and smelled of swamp.

Interrogation

Investigators were especially interested in the Azov soldiers. During interrogation, prisoners had to stand bent over, unable to look at the interrogator. If answers were unsatisfactory, the Russian guards would beat POWs with their hands and feet. If there was any perceived justification to accuse the Ukrainian soldier of “criminal orders,” the abuse intensified to severe beatings and finger breaking to demand a confession.

Ryazhsk Pre-Trial Detention Center (SIZO-2), Ryazhsk, Ryazan region

The transfer to Russian prisons was marked by further cruelty: AA flew for six hours on the floor of a plane, with his hands bound and eyes taped, sitting between the legs of the next prisoner. He reported that the Russian guards selectively beat prisoners throughout the whole flight to Ryazhsk, Ryazan region, southeast of Moscow.

At this center, cells were designed for 3–10 people, and sleeping arrangements were adequate; however, hot water for weekly showers was scarce.

On each floor, there’s an interrogation room where interrogations with torture are conducted. In these rooms, they have a 'gentleman’s kit' on the table: PVC pipes used for beatings, two types of stun guns, a box of needles used to drive them under their fingernails, and bags that they place over the interrogated’s head and suffocate them.

Former Ukrainian POW AA recalls

the Ryazhsk Pre-Trial Detention Center

“Nearby, there’s a container of water and ice to revive those who have fainted,” AA said. “Sometimes, they would lower the interrogatee’s head into this same container and drown him there as a form of torture.”

Russian investigators interrogated AA approximately 35 times over two and a half months, with sessions lasting between 30 minutes and 1.5 hours.

Beyond the interrogation room, prisoners were regularly beaten during morning roll calls. Russian Special Forces and Federal Penitentiary Service officers often beat prisoners for sport, labeling the violence as punishment for “violating the regime.” On February 7, 2023, AA was transferred to the Correctional Colony №10 in the Republic of Mordovia, located further east.

Correctional Colony IK-10, village of Udarny, Republic of Mordovia

Upon arrival, prisoners underwent an extremely harsh “acceptance” process: Russian guards forced POWs to strip quickly, while severely beating them with plastic pipes during the entire 40-minute ordeal. Many were forced to lie on the ground and were struck on their heels, buttocks, and genitals.

For most of the day, prisoners were required to stand still—they could not walk, sit, talk, lean, or even shift their weight. This prolonged standing caused many to develop swollen veins in their legs, and some even suffered gangrene. Toilet breaks and access to drinking water were strictly limited to specific commands.

Guards sometimes set dogs on the prisoners during morning runs: “One morning, we ran out into the hallway,” AA said. “There was a German Shepherd there […] it bit me twice: on my legs and then on my arms. But she turned out to be much kinder than people. At first, the Shepherd simply bit me and let go, and the second time, the handler gave commands: grab, tear, bite, and the Shepherd began to bite me very hard.”

His cellmate had a piece of skin torn from his elbow by a dog, and the wound festered for a long time.

The colony guards devised physical tortures for “entertainment,” subjecting POWs to shocks across the entire body, including the genitals and the anus. They would order prisoners to perform grueling exercises, such as 700 squats or synchronized squats (100 times, restarting if anyone faltered). AA noted: “After three minutes of such exercises, we could not feel our legs.”

SIZO-2, Stary Oskol, Belgorod region

After being transferred from Olenivka, BB was placed in SIZO-2 in Stary Oskol—a city about 150 kilometers (93 miles) from the Ukrainian border. He was held in a cell designed for eight but housing ten, equipped with cold water, a sink, and one communal mug.

BB recalls prisoners being beaten 3–4 times a day for any reason, or no reason at all. A young soldier complaining of a toothache was denied medication. Instead, a Russian special forces officer entered the cell, struck him with a stick, and mockingly asked if the tooth still hurt.

Special forces guarding the prisoners rotated every three to four weeks. BB noted one exception: a group of Caucasians (likely Dagestanis) who treated them better than others, joking with them and rarely resorting to violence. The rest of the guards were consistently cruel.

SIZO-2, Taganrog, Rostov Region

Upon arrival, prisoners, whose eyes were bound, were thrown from the trucks and severely beaten. This abuse was carried out in two stages: first, near the transport, and then for about 90 minutes in a separate garage-like room. One prisoner noted, “I was genuinely happy when I managed to lose consciousness and take a break.” The guards revived them by pouring ammonia directly from the bottle into their noses.

Prisoners were forced to learn and sing the Russian anthem, songs like “Katyusha,” and “Smuglyanka,” and to memorize the poem “Forgive Us, Dear Russians.” When errors occurred during recitation, guards would beat the entire cell.

Death of a Polish citizen

In mid-2022, guards at SIZO-2 regularly beat a detained Polish citizen, reportedly because he refused to learn Russian and due to Poland’s support for Ukraine. One group of Russian guards beat him so severely that his legs turned blue and began to fail. He died from his injuries in mid-June 2022. Afterward, they forced his cellmates to sign statements denying any abuse or conflict.

Following this death, the frequency of physical beatings during checks decreased, but the guards intensified the mandatory physical drills, with squats starting at 200 and push-ups at 100.

SIZO-2, Galich, Kostroma region

Interrogations ran daily from 8 AM to 11 PM (sometimes continuing overnight), where guards would beat POWs and use electroshockers. They would force prisoners to destroy or remove pro-Ukrainian tattoos and symbols on their own bodies using a knife or wire.

Numerous instances of sexual violence were reported at Galich, including: applying electroshockers to the genitals and/or anus. Blows to the groin area, forcing prisoners to sit on a bottle and perform slow dances and striptease.

SIZO-3, Kizel, Perm region

In September 2024, a significant number of Ukrainian prisoners of war and civilian hostages who had not yet been formally charged were transferred to SIZO-3 in Kizel. The transit from Rostov to Perm alone took three days. Upon arrival in Kizel, the “acceptance” process was exceptionally brutal. One prisoner recounted:

“They put a sack over my head and beat me with all their might. My right arm was broken from the elbow to the wrist. I collapsed unconscious upon reaching the cell.”

Following such a brutal beating during the “acceptance” process, Yevhen Matvieiev, the mayor of Dniprorudne (Zaporizhzhia region), died in SIZO-3. His body was transferred to his family in December 2024. Matvieiev was detained by Russian forces on March 13, 2022, at one of the Russian checkpoints on the way out of the city of Dniprorudne.

Investigative reports (Slidstvo.Info) suggest that Ukrainian journalist Viktoriia Roshchyna, who disappeared in Russian-occupied territory in August 2023, died on September 19, 2024, in SIZO-3 in Kizel. She had been transported there from Taganrog earlier that month.

The testimonies of torture mentioned above are part of a systematic pattern used by the Russian government to destroy detainees both physically and psychologically. Such actions constitute blatant violations of international humanitarian law and the Geneva Conventions.

This report, in addition to thousands of other stories, serves as a definitive call to the international community to hold the Russian criminals accountable for their abuse.

-457ad7ae19a951ebdca94e9b6bf6309d.png)

-f88628fa403b11af0b72ec7b062ce954.jpeg)

-29a1a43aba23f9bb779a1ac8b98d2121.jpeg)

-76b16b6d272a6f7d3b727a383b070de7.jpg)