- Category

- War in Ukraine

War Costs Soar, Oil Prices Sink: Russia’s Coffers Are Running Out of Cash

By only mid-2025, Russia’s budget deficit has blown past the limits set for the entire year, draining Kremlin coffers as military spending soars. And there is no clear plan to fill the gap.

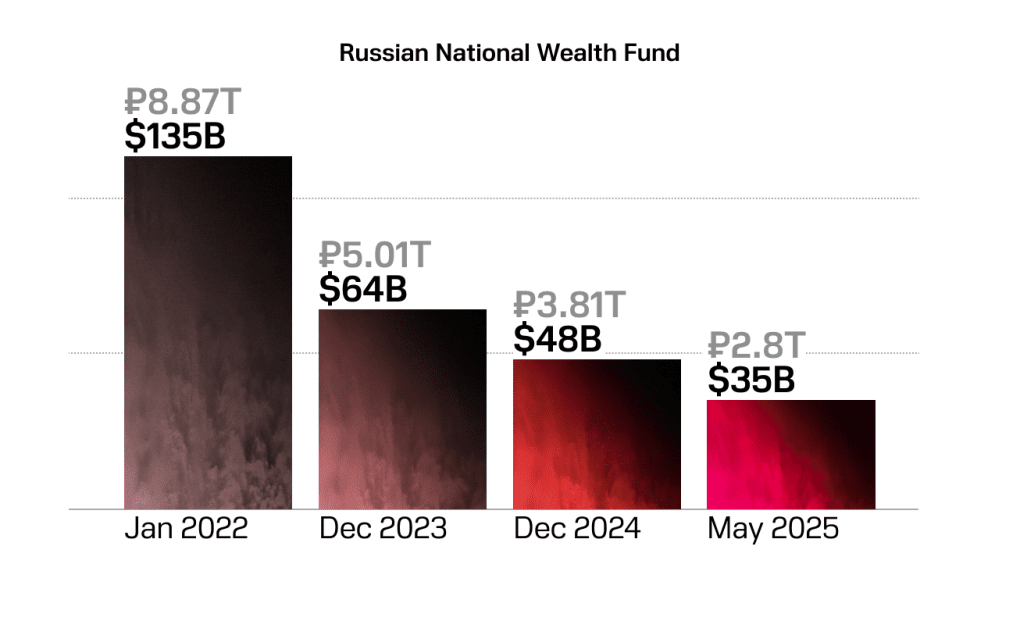

Russia is often called “a gas station masquerading as a country” for good reason: its economy is heavily dependent on oil and gas exports. These resources contribute between 40% and 60% of state revenue, depending on global energy prices, covering most government needs. Oil and gas windfalls also helped build Russia’s National Wealth Fund, which at its peak held nearly 9 trillion rubles ($113 billion).

High oil prices in 2022–2024 allowed Russia to cover foreign currency needs and finance its war. Officially, the Kremlin spent nearly $400 billion over three years; unofficially, bank financing added another $250 billion.

Spending on the war to destroy Ukraine in 2025 is now projected to exceed earlier estimates, rising from $142 billion in the budget to about $170 billion. The problem is that there is no clear source of financing: Russia is short on cash and has few borrowing options.

A budget in deep red

As of June 2025, the federal budget deficit stood at 3.7 trillion rubles (about $46 billion)—roughly the amount originally forecast for the entire year. Officials insist the situation will balance out by year’s end, noting that the heaviest spending typically occurs early in the year, as it did in 2024.

But the outlook is bleak. The deficit already equals about 1.7% of GDP, compared to the 2025 plan of 0.5%. If the gap is not reduced, the Kremlin’s economic managers face a bind: even the National Wealth Fund, once a substantial reserve, holds only 2.8 trillion rubles ($35 billion) as of midyear.

Under government rules, the fund is replenished only when oil prices are high—something the current market is not delivering.

How cheap oil hurts the Kremlin

Low energy prices are now Russia’s biggest headache. The 2025 budget was based on oil averaging $66 per barrel. But recent trends suggest a full-year average of $55–$65, below Moscow’s assumptions.

In the first half of the year, the oil slump cost the budget 25% of projected revenue, with overall income down 17% year-on-year. In July, oil export tax revenue fell 33%, while combined oil and gas income dropped 27%. The average sale price in July was $59 per barrel—about 10% below budget forecasts.

Two additional factors are compounding the problem:

Domestic fuel shortages. Russia sells not only crude oil but also refined products such as gasoline. Russian refineries have suffered repeated Ukrainian drone strikes, tightening the domestic supply—covered this in detail in this article. Gasoline prices at home have soared, forcing producers to a) cut exports, b) pump more supply into the domestic market to appease both consumers and the Kremlin, and c) sell crude and refined products at lower prices, slashing profits. In July 2025, each exported barrel brought in 4,711 rubles (about $56) instead of the 6,127 rubles ($75+) budgeted.

Global market trends. OPEC (Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries) plans to increase production, while global oil demand remains flat. Adding to the pressure, US President Donald Trump has urged India to reduce imports of Russian crude.

Together, these factors limit the Kremlin’s ability to boost revenue.

Why sanctions matter

Unless oil prices suddenly double, Moscow will struggle to cover its deficit. Borrowing abroad is not an option—Russia has been shut out of global capital markets, and foreign lenders remain wary, recalling that the Russian Empire never repaid the funds it had borrowed from France to finance World War I.

That leaves raising taxes, issuing bonds and buying them domestically, or weakening the ruble. Even if Russia finds alternative buyers for its oil, sanctions targeting its shadow fleet mean it will have to ship crude farther afield at higher costs.

All of this is unlikely to bolster domestic confidence in Russian leader Vladimir Putin. And with war spending off-limits for cuts, other sectors will bear the brunt.

For the first time, sanctions pressure appears to be creating tangible internal strain—and, potentially, an incentive for the Kremlin to come to the negotiating table.

-29a1a43aba23f9bb779a1ac8b98d2121.jpeg)

-347244f3d277553dbd8929da636a6354.jpg)

-f88628fa403b11af0b72ec7b062ce954.jpeg)

-554f0711f15a880af68b2550a739eee4.jpg)