- Category

- World

What Is Russia’s New Law That Makes Googling a Crime?

Russia’s new law punishes online searches for so-called “extremist” content, branding searches about the war, resistance, or LGBT rights as criminal, turning clicks and freedom of thought into criminal acts.

Russia’s State Duma has passed a new legislation introducing fines for searching prohibited material online, including when using a VPN.

The Russian Constitution “guaranteed” the rights to freedom of thought, speech, and information, but that’s being severely restricted. This marks the first time, even amid sweeping internet crackdowns, that searching, not just creating or distributing what they brand as extremist content, is grounds for a penalty.

Individuals would face a fine of around $65 for “searching for or accessing knowingly extremist materials,” while advertising for tools such as VPN services would be $2,500 for individuals, and up to $12,800 for companies.

“It does not matter why a person is looking for such information—for artistic, research, or scientific purposes. Any act will be punished if it is recognized as a deliberate search,” according to Russian reports.

Once again, the Russian authorities are disguising their relentless persecution of dissent as countering ‘extremism’ through vague and overly broad legislation, which allows for abusive interpretation and arbitrariness.

Marie Struthers

Amnesty International’s Director for Eastern Europe and Central Asia

The new legislation that will officially take effect from September 2025 is yet another move by the Russian regime to censor and restrict information, with especially disturbing consequences to parts of Ukraine currently under Russian occupation.

The vague wording allows millions to become violators, even unknowingly clicking a link will be enough for a penalty. “The law will give rise to a wave of fraud, doxxing, blackmail, and extortion. It will be easy as pie to set someone up,” the head of the "Safe Internet League ,” Ekaterina Mizulina warned.

The new restrictions are yet another form of the Kremlin's control over the internet, which has accelerated since Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine.

What is Russia’s definition of “extremism”?

Russian authorities frequently invoke the supposed justification of extremism—even where none exists—as a means to legitimize crackdowns that are both arbitrary and brutally severe.

Russia targets a range of activities from social media posts, websites, etc, that are of pro-Ukraine sentiment, oppose Russia, and even some religious material.

These so-called “extremist materials could be anything from a book ‘promoting same-sex relationships’ to social media posts by opposition groups,” Marie Struthers, Director at Amnesty International Eastern Europe and Central Asia, said.

Namely, anything that the Kremlin deems not to fit its “traditional values” falls under its extremism category.

(Russia’s extremism strategy contains) clear updated instructions for the Russian security service on how to persecute Ukrainian citizens, crush resistance on occupied territory and destroy any demonstrations of Ukrainian identity, with this totally in accordance with the aims of the Russian Federation’s genocidal war against Ukraine.

Head of Crimean Human Rights Group

Even the infamous meme of a drawn Putin wearing makeup in front of an LGBT flag is considered extremist material in Russia. Before this law, the meme was illegal to share; now it's a punishable offence to even search for or click on.

On Russia’s Federal extremist materials list, the meme is listed as; #4071 “A poster depicting a man resembling Russian President V.V Putin, with makeup on his face — painted eyelashes and lips”

Opposing Russia’s war in Ukraine is “extremism”

There are over 5000 items on Russia’s list of so-called “extremist materials,” including any Ukrainian websites, along with material on Ukrainian culture and history.

Websites stating facts about Russia’s war of aggression against Ukraine have either already been banned as “extremist” or are almost certainly blocked, Kharkiv Human Rights Protection Group (KHPG) said.

School students in Russian-occupied regions of Ukraine are already subject to random searches to check whether they’re using Ukrainian websites or distance learning apps, KHPG said, and warns that they’re likely to become more frequent.

In January 2023, all educational institutions in Russian-occupied Luhansk region were sent a list of supposedly “extremist” books to be removed.

That includes literature about Holodomor, a Moscow-made genocide and famine killing around 7 million people, Ukrainian history, and any “publicist, research, or monitoring” material published after 2014, the year Russia initially invaded Ukraine.

As Ukrainian sites are blocked, Ukrainians in occupied territory rely on VPNs to access information and contact with family in other parts of Ukraine. “The new law will increase the likelihood of spot checks on occupied territory, with yet another weapon now available for persecution,” KHPG said.

A Ukrainian woman from the Russian-occupied Luhansk region was sentenced to 10 years’ imprisonment on “terrorism and extremism” charges for allegedly donating to “Azov” of Ukraine’s Armed Forces and to an organization that no longer even exists.

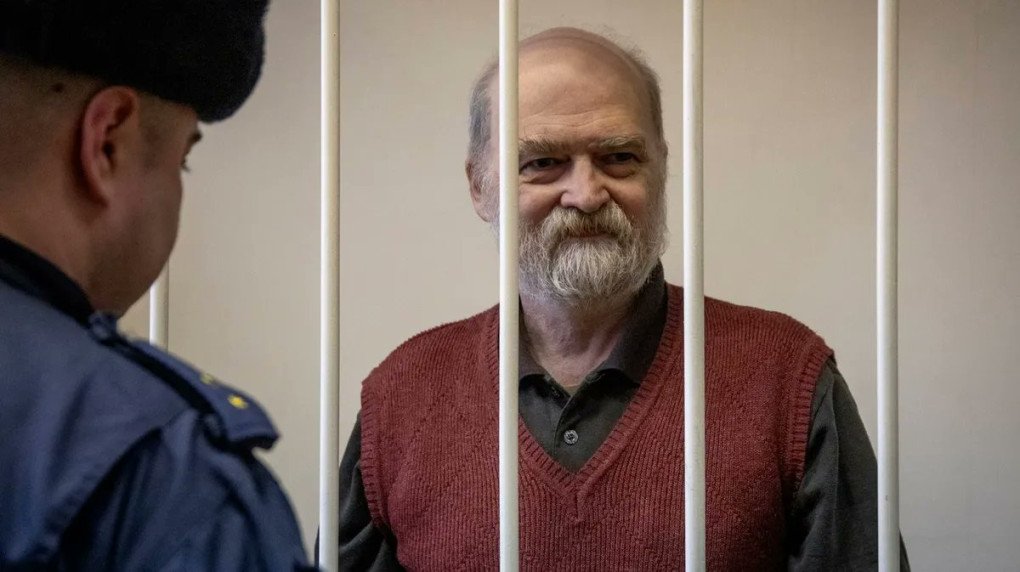

In March 2025, Alexander Skobov, a 67-year-old “lifelong dissident,” was sentenced to 16 years in prison over a social media post supporting Ukraine’s 2022 strike on the illegally built Crimea Bridge.

Today, I will be asked whether I plead guilty. Well, I am the one making the accusation here! I accuse the stinking corpse of a regime and the ruling Putin clique of preparing, unleashing, and waging an aggressive war, of committing war crimes in Ukraine, of political terror in Russia, and of the moral corruption of my people.

Russia has already prosecuted 1472 people in temporarily occupied Crimea for expressing solidarity with Ukraine. In July 2025 alone, there have been several instances targeting pro-Ukrainian voices for posting on social media, let alone searching for information, the Crimea Platform reported.

A resident of the Simferopol district was detained for posting an image on social media featuring the Ukrainian and Crimean Tatar flags, along with the caption “Crimea is Ukraine. And no one can stop it.”

In the city of Saky, a man was detained by Russian forces for listening to music in Ukrainian.

A resident of Sevastopol was detained by Russian occupation forces for posting critical comments about the Russian army and regime on social media.

A resident of occupied Sevastopol was detained by Russian forces for posting social media content critical of Russia’s military

A resident of Kerch was arrested after posting a comment on social media about a Ukrainian drone attack on the Kremlin.

A resident of Simferopol held an anti-war protest with a sign reading “No to war” in the city center and was fined and subjected to a forced psychiatric evaluation.

LGBTQ+ is “extremism” in Russia

In January 2024, the LGBTQ+ Movement became an extremist organisation, and almost anything LGBT related was grounds for raids, arrests, and fines.

Mothers were charged with “improper performance of parental responsibilities” by posting on Facebook, and even the father of a transgender teenager was deprived of his parental rights.

Between January 2024 and June 2025, at least 20 people were criminally charged for their alleged links to the so-called “International Public LGBT Movement,” Human Rights Watch (HRW) reported.

One of the accused took their own life in pretrial detention. Two have already been sentenced, and the other cases are still pending.

Three publishing staff were charged and face 12 years in prison for “running an extremist organization” for the crime of selling fiction that included LGBT themes in May 2025, HRW reported.

Russian authorities claim that these books were not literature, but recruitment tools.

In January 2024, authorities punished 81 people in 98 court cases under administrative law for displaying LGBT symbols like the rainbow flag, most often online, HRW found.

Given the routine abuse of extremist and anti-terrorism laws, individuals exercising their legitimate right to free expression are increasingly being labeled and prosecuted as threats to the state.

How will Russia enforce this new law?

Experts say that Russia’s law enforcement agencies can receive data on "offenses" from telecom operators and may even stop and search random individuals on the street, examining their phones.

Search engines and social media platforms have consistently fulfilled Roskomnadzor’s requests as required by Russian law, which includes collecting, storing, and handing over users’ search queries upon request.

People, specifically Ukrainians in occupied territory, are also at risk of entrapment. DNS spoofing is a common tactic where a malicious actor sets up a public Wi-Fi network and reroutes traffic, making it appear as though connected devices accessed banned websites.

This results in false digital footprints, making a device appear to have accessed a banned website. This could be used against Ukrainians in occupied territories to further control the population.

Russia’s online crackdown

Russia blocked nearly 800,000 web pages in 2024 alone, 19% more than in the previous year, Interfax reported.

Russia has become one of the most surveilled and censored digital environments in the world. The state has passed sweeping legislation criminalising “discrediting the military”—punishable by up to 15 years in prison.

The government aggressively blocks or slows access to a wide range of websites, social media platforms like X, Facebook, and Instagram, etc; therefore, VPNs are widely used to circumvent the blocks of internet sites.

This picture is officially considered extremism in Russia. Punishable by up to 5 years in prison. pic.twitter.com/gVkxVsTS0s

— Atheist Republic (@AtheistRepublic) April 8, 2017

In July 2024, Apple removed 25 VPN services from the Russian App Store. In 2023, Google complied with 54% of content removal requests, and in 2024, YouTube (owned by Google) blocked videos about draft evasion in Russia.

The majority of these requests were through Roskomnadzor (RKN), which is a Russian federal executive body that regulates communications, information technologies, and mass media.

RKN uses deep packet inspection (DPI), which allows RKN to identify and block access to sites that are blacklisted, along with collecting detailed information about how users use the internet, which can be used for further analysis and action.

In the second quarter of 2023, more than 130,000 web pages were deleted or blocked by Roskomnadzor, 26 thousand of them allegedly “publishing false information about Russian military actions in Ukraine”, Statista reported.

Inside Roskomnadzor, there is a whole state enterprise that employs more than 1,000 people looking for published material critical of Putin, and their reports are sent to the Presidential Administration of Russia and the security forces, according to an investigation by Istories and Süddeutsche Zeitung.

Russian censors have classified any reporting on the killing of Ukrainian civilians, the destruction of civilian infrastructure, Russian military losses, or soldiers refusing to fight as prohibited content.

Nasiliu.net is an organisation working on domestic violence in Russia, which reported problems receiving messages from victims in June 2025. Within a week, its telecom operator abruptly terminated its service, effectively inactivating the SOS button in its app—a key emergency tool for domestic violence survivors, OVD-Info reported.

Russia today: while Putin's rubber-stamp parliament considers introducing penalties for just searching online of materials declared “extremist” by the authorities, the police detain a protester carrying a banner reading “Orwell wrote a dystopia, not a manual!” pic.twitter.com/ImZYYdYIHx

— Rim Gilfanov (@guilfanr) July 22, 2025

This new law will have “the most massive example of chilling effect in the history” of the Russian internet, an anonymous representative from digital rights group Setevye Svobody, told Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ).

The law “will make tens of millions of users prefer to unsubscribe from the channels and stop visiting sites with information of any unofficial nature,” the representative added.

Given the systemic misuse of extremist and terrorist legislation, this leads to the listing of people persecuted for the legitimate use of the right to freedom of expression

The representative from digital rights group Setevye Svobody, who spoke to CPJ on condition of anonymity for fear of reprisal, told CPJ he expects “the most massive example of chilling effect in the history” of the Russian internet.

Fines for reading online articles featuring so-called extremist content “will make tens of millions of users prefer to unsubscribe from the channels and stop visiting sites with information of any unofficial nature,” the representative said.

-46f6afa2f66d31ff3df8ea1a8f5524ec.jpg)

-7e242083f5785997129e0d20886add10.jpg)

-605be766de04ba3d21b67fb76a76786a.jpg)

-88e4c6bad925fd1dbc2b8b99dc30fe6d.jpg)

-206008aed5f329e86c52788e3e423f23.jpg)

-7ef8f82a1a797a37e68403f974215353.jpg)

-29a1a43aba23f9bb779a1ac8b98d2121.jpeg)