- Category

- Anti-Fake

20 Years of RT: How Russia’s Propaganda Hydra Survived the Ban

Despite bans across Europe, the US, and Canada, Russia’s state-funded network RT is far from gone. The Kremlin’s favorite media weapon has morphed into a hybrid propaganda machine—streaming through smaller platforms, partner outlets, and social media ecosystems that still reach millions. Data reviewed by UNITED24 Media shows how RT adapted its playbook after 2022, turning sanctions into an opportunity to rebrand and retarget new audiences.

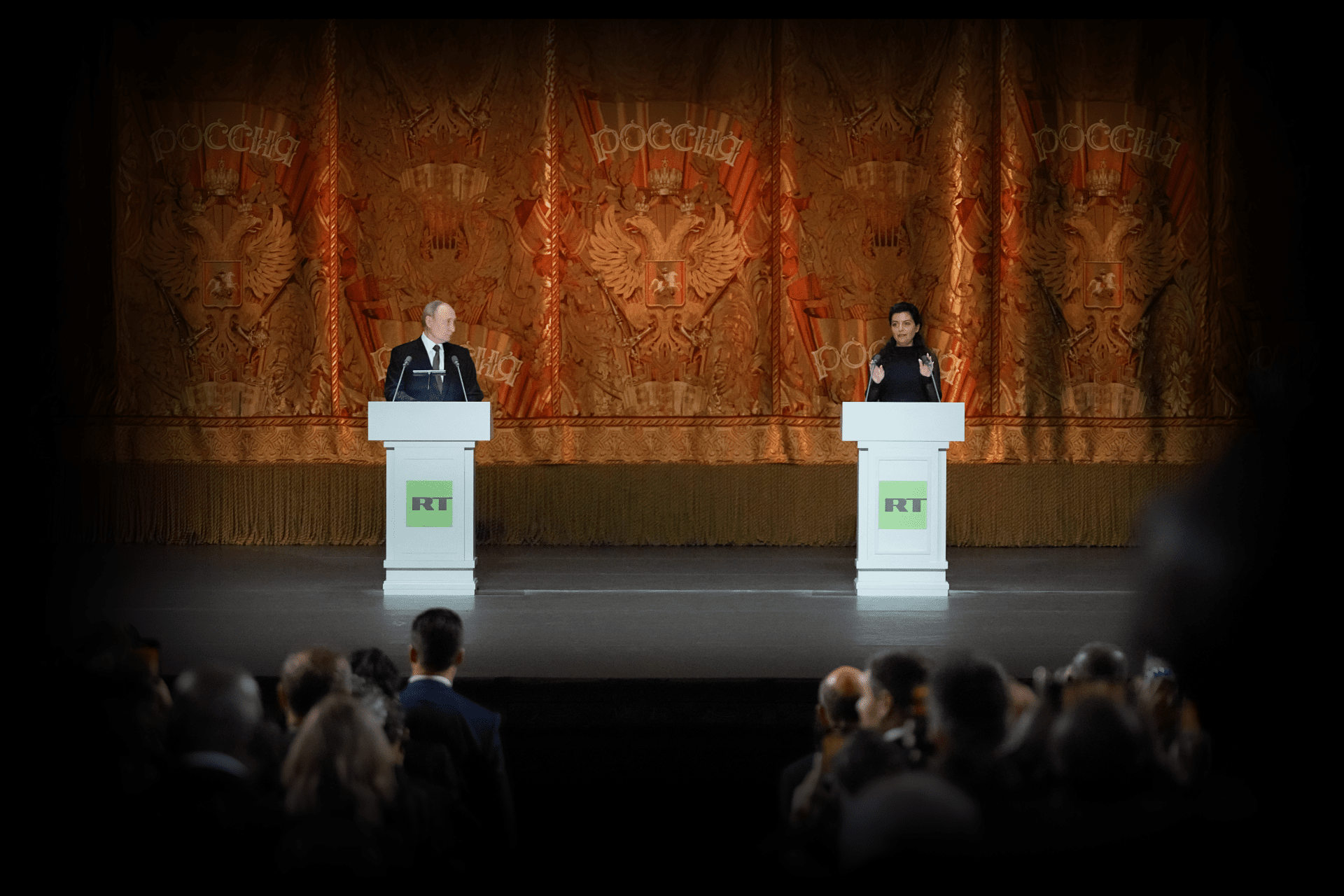

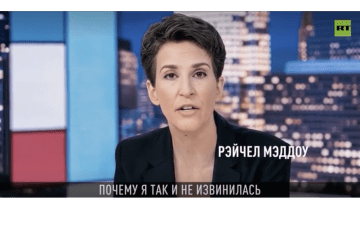

To mark 20 years since its creation, Russia’s foreign propaganda channel RT (formerly Russia Today) produced and posted a deepfake video that uses AI tools to generate several of the most popular American anchors, among them Anderson Cooper (CNN), Rachel Maddow (MSNBC) and Sean Hannity (Fox News). Framed as a long confession stitched from fragments “spoken” by each of them, the Russian channel accuses these journalists of lacking objectivity and serving only the interests of the US government.

The channel, which presents itself as an alternative to “mainstream” international media, marked its 20th anniversary in October 2025 by producing and publishing a fake video—supposedly to show that journalism lacks objectivity. In it, Piers Morgan “says”, “Why I always ask ‘Do you condemn Hamas? ’ but never Israel?” while Sean Hannity “asks,” “Why do I support every illegal war the US has launched this century?” Although the video features American anchors, this “anti-imperialist” message doesn’t seem aimed at a US audience.

Rather, it targets Russia’s new media priorities since sanctions weakened its access in Europe and North America: countries in the Middle East, Africa, South America, and Southeast Asia.

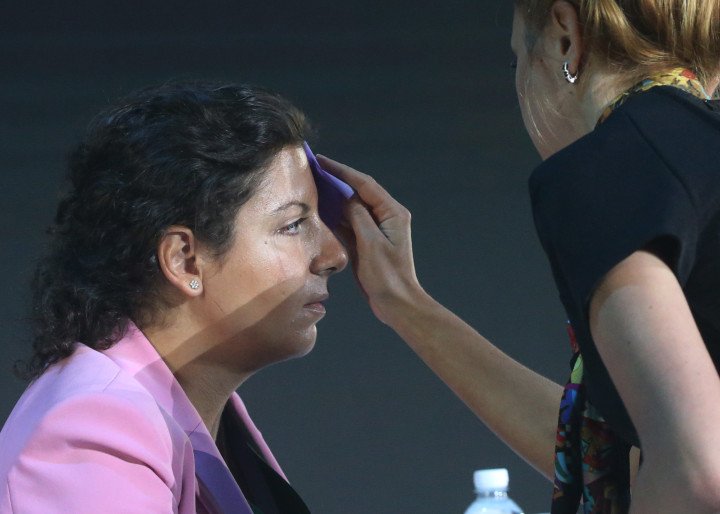

On October 5, a Russian “journalist”—not AI-generated this time—denied, in near-fluent French, the existence of evidence proving that NATO countries were attacked by Shahed drones launched from Russia, or by reconnaissance drones launched from ships in its shadow fleet. She did so on CNews, one of France’s three major rolling-news channels, using rhetorical techniques RT had honed for years: with a compliant host, she diverted attention from facts by claiming that the fear these incursions provoke actually serves Europe more than Russia by accelerating its defense rearmament—without indicating what legitimate threat this rearmament is meant to counter.

Her name is Xenia Fedorova, and she is the former head of RT France, one of the network’s foreign-language arms and overseas bureaus. For several years, RT France served as Russia’s principal “information warfare” agency in France. It took more than a year after Russia’s unprovoked full-scale invasion of Ukraine for RT France to be wound up. Even today, its influence and destabilization networks remain tolerated—and even legitimized—in France, as seen with Fedorova’s weekly pundit role on CNews. The pattern is similar across all seven of RT’s broadcast languages, especially in countries that implemented sanctions to varying degrees, such as the UK and Germany.

In reality, the Kremlin’s main foreign propaganda channel isn’t dead—it adapted to a new environment by focusing on adversaries’ weaknesses. At a time of war, budget cuts in traditional media, and the end of US support for certain news and investigative outlets broadcasting in Eastern Europe, the question is urgent. After more than three years of full-scale war and bans across most Western countries—its prime targets—what is the state of the Kremlin’s most potent information weapon?

RT’s “information war” against the Western world

Since the start of the full-scale invasion, roughly $6.05 billion has been spent on state propaganda. Despite being hit economically by Western financial sanctions and Ukraine’s “kinetic” military pressure, Russia has recently proposed doubling investment in its propaganda tools, which were already heavily subsidized. According to research by Maxime Audinet in his reference book on the channel, RT’s budget in 2008 was 3 billion rubles. Today, RT controls a budget of $388 million (32.08 billion rubles).

Like the rest of Russia’s military sector—which now represents 41% of the state budget—RT’s allocations keep rising.

Margarita Simonyan, who has led the channel since its inception, summed it up as early as 2012 in an interview titled “There is no objectivity,” given to the Kremlin-friendly paper Kommersant: it is essential to use public funds for “conducting the information war […] against the whole Western world.” In 2018, in another interview, she added: “The Defense Ministry fought against Georgia, but we waged an information war against the entire Western world.”

RT’s evolution into a weapon of mass destabilization

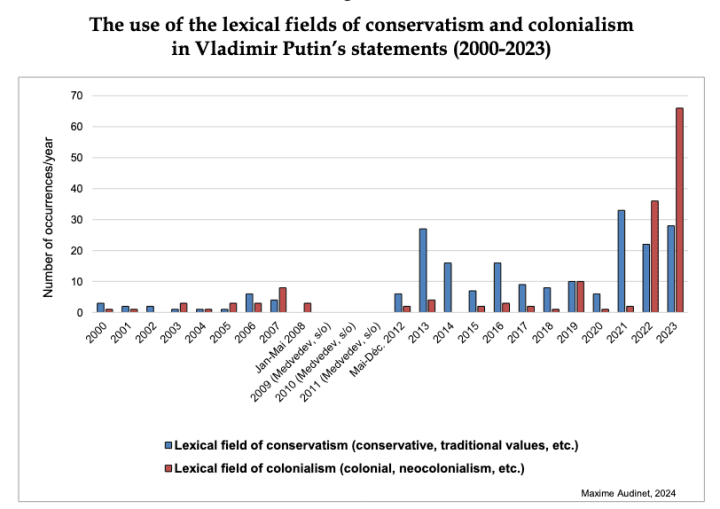

Created in 2005 under Putin’s direct supervision, RT quickly evolved from a Russian branding channel into a weaponized global broadcaster, exploiting each political crisis to amplify Kremlin narrative and destabilise its enemies.

25-year-old journalist Margarita Simonyan — known for her reporting from Chechnya and on the Beslan school hostage crisis — was appointed head of the channel at its launch.

This was a pivotal moment in Putin’s reassertion of control over the media, as he began his second term. From the outset, RT carried the Kremlin’s weight.

But the channel gained its first major traction in 2008 thanks to its supposedly “alternative” coverage—that is, echoing the Kremlin’s deceptive narratives, criticized by media worldwide—of Russia’s assault on Georgia and further occupation of its territory.

RT’s audience soared and bureaus opened around the world. Initially in English and Russian, the channel added Arabic, Spanish, German, and French services. According to Maxime Audinet, a French researcher specializing in Russian state media and propaganda, and author of Russia Today (RT): A Weapon of Influence (2021), the Russian channel then shifted away from covering only Russia to becoming an overseas megaphone for “alternative,” anti-system, conspiratorial, pro-Russian, and cynically minded voices—as well as defectors from so-called “mainstream” media—offering significant resources in staffing, distribution, and salaries.

High-profile intellectual figures—not presumed to have any particular attachment to Russia’s authoritarian regime—appeared on or collaborated with the channel: US senator and presidential candidate Bernie Sanders in 2012, Slovenian philosopher Slavoj Žižek up to January 2022, and even Wikileaks founder Julian Assange.

While Russia Today stayed largely silent on the 2006 poisoning of Alexander Litvinenko, a former FSB officer who defected to the UK and was killed with radioactive polonium, it later flooded the internet with contradictory claims about the poisoning of Sergei Skripal, another ex-Russian intelligence agent, and his daughter in the UK in March 2018. Analyzing 735 RT and Sputnik pieces in the month after the Skripal poisoning, researchers documented 138 distinct and contradictory narratives explaining the incident. The same pattern held in Syria, where RT’s correspondents and field teams bolstered Bashar al-Assad’s crimes; one correspondent was later killed in a bombing.

Drawing on Yochai Benkler ’s theory, Audinet explains this as RT’s method of “disorientation”—diluting “the most reliable, truthful, or factual information by simultaneously or successively disseminating alternative and contradictory versions.”

A confused, passive reader is left unable to distinguish reality from fiction, truth from falsehood.

Maxime Audinet

Author of Russia Today (RT): A Weapon of Influence (2021)

From 2008 to today, Audinet argues, RT has pursued a strategy of destabilization, harvesting audience gains at every political event that could split societies—and ideologically adapting each time: Occupy Wall Street (2011), the war in Syria (2011–2024), the Black Lives Matter movement (2013–2014), US presidential elections (2016), Israel–Palestine. During France’s Yellow Vests crisis (2018–2019), RT’s views climbed from 7.1 million in November to 12.4 million in December, to 12.9 million in January, before dropping to 8.8 million in February as the crisis faded.

Western countries ban RT’s broadcasting—but not its operations

Western countries acted decisively only after Russia launched its full-scale invasion in 2022, attempting to curb RT’s activities.

The Council of the EU announced on March 2, 2022, that RT’s broadcasting activities would be suspended until the end of Russia’s unprovoked aggression against Ukraine and as long as Russian media continued information manipulation and interference targeting the EU. The decision specifically named RT English, RT UK, RT Germany, RT France, and RT Spanish.

But the restrictions targeted the channel’s broadcast licenses—not its content production or its legal presence in countries where it operated.

“The enforcement of sanctions on Russian state media by European ISPs remains inconsistent,” said the Institute for Strategic Dialogue, a UK based think tank. “Across the three largest ISPs in six Member States, less than a quarter of attempts to access the content were effectively blocked.”

The day after Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine, many non-Russian employees of Ruptly—RT’s Berlin-based video production agency—resigned in protest. Management had instructed staff to refer to the war only as “the Russo-Ukrainian conflict,” avoiding the word “war.” Despite the resignations, Ruptly continued its work for more than a year after February 2022, as German authorities lacked swift tools to shut the subsidiary down.

Soon after, Ruptly’s director, Dinara Toktosunova, resurfaced in the United Arab Emirates to announce the creation of a new video agency, Viory. The company effectively took over Ruptly’s activities under a new name and jurisdiction—a “scaled-down” version of it, offering content in Arabic and English, while dropping Spanish and Russian, once provided by Ruptly.

In March 2022, Ofcom revoked RT’s broadcast license in the UK due to concerns about its relationship with the Russian state and Russian laws limiting freedom of speech, which made it impossible for RT to comply with impartiality rules.

Without a license, RT France proceeded to liquidation in spring 2023, with studios operating until then. Today, the channel has shifted back to Moscow and continues from Russia.

One of the most significant blows to RT’s outreach was its ban from Meta (Instagram, Facebook, WhatsApp), notably across the Global South: Africa, the Middle East, and India.

RT’s transformation into an “information guerrilla”

Since its ban, RT has seen many of its local channels and correspondent bureaus shut down one by one. Yet by exploiting slow enforcement, local media allies, and regional repositioning, it appears to keep reaching large audiences, with Russian operatives still present on the ground—without a response from national authorities commensurate with the threat.

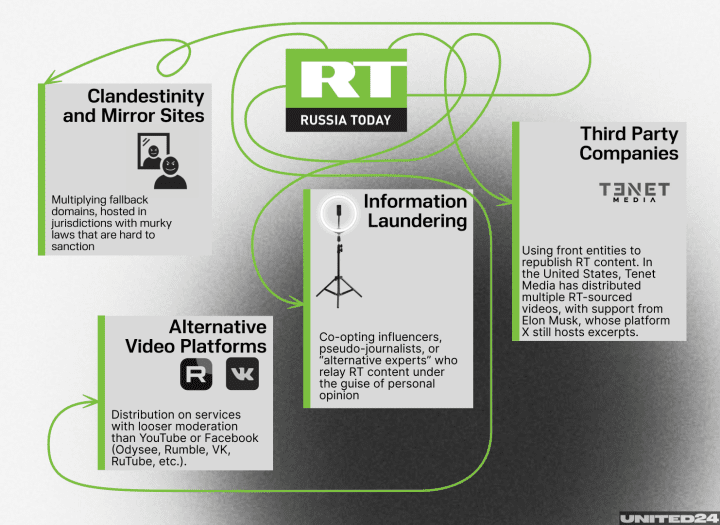

Simonyan now openly calls it an “information guerrilla.” In a piece for Le Monde, Audinet lists these RT’s new tactics to bypass EU sanctions:

Clandestinity and mirror sites: multiplying fallback domains, hosted in jurisdictions with murky laws that are hard to sanction.

Alternative video platforms: distribution on services with looser moderation than YouTube or Facebook (Odysee, Rumble, VK, RuTube, etc.).

Third-party companies: using front entities to republish RT content. In the United States, Tenet Media has distributed multiple RT-sourced videos, with support from Elon Musk, whose platform X still hosts excerpts.

— Elon Musk (@elonmusk) July 29, 2024

Information laundering: co-opting influencers, pseudo-journalists, or “alternative experts” who relay RT content under the guise of personal opinion (see UNITED24 Media investigation).

In 2024, Simonyan confirmed RT’s heavy use of artificial intelligence to produce content: • Automatic generation of articles and images; • Creation of fake journalists; • Synthetic voice cloning for English-language videos.

We have a significant proportion of TV presenters who do not exist. They don’t exist, they are artificial completely. This person doesn’t exist, and never did. This face never existed, we generated the voice, everything else, the character

Margarita Simonyan

RT Editor-in-Chief

Inside RT’s reinvention in the UK, France, and Germany

RT remains active in at least seven languages, but three cases show its adaptability in sanctioning countries.

United Kingdom—RT International / RT UK

Despite Ofcom’s license revocation in March 2022—and despite RT UK’s already small TV audience—the brand maintains a strong online presence thanks to:

Relocation of several technical teams to Dubai.

Exploitation of divisive themes: immigration, sovereignty, Islamism, monarchy.

Indirect participation in amplifying radical narratives during the summer 2025 riots.

“Kremlin action has become parasitic: it amplifies existing fractures rather than creating new ones.” — Analyst at King’s College London

Afshin Rattansi, an RT UK host, relocated to Dubai and continues his show, Going Underground, for a pro-Assad and pro-Palestinian audience.

France—RT France / RT Africa

In France, RT was liquidated in 2023, over a year after Russian bombs began devastating Kyiv.

Even so, its already mentioned leading figure, Fedorova, continues to appear and share pro-Kremlin rhetoric on CNews, part of the Vincent Bolloré group. Reporters Without Borders (RSF), a Paris-based international NGO that defends press freedom and monitors violations against journalists worldwide, has compared the Bolloré media ecosystem to state propaganda structures observed in Russia, giving Fedorova a platform that normalizes her analyses in public debate.

The Bolloré group has provided an echo and resources comparable to what we see in Russian state media.”

Thibaut Bruttin

RSF general director, in an interview with UNITED24 Media

Mirror sites were also activated to keep RT France accessible.

Germany—RT DE

Germany was among the first to ban RT. But since 2023, mirror sites like freed**.online (up to 690,000 monthly visits) have continued to host its German-language content for an almost exclusively domestic audience.

Former RT DE and Ruptly journalists regrouped in “independent” structures in Dubai (Viory) or Leipzig (Red), perpetuating RT DE campaigns under new names and formats.

RT’s audience persists despite bans

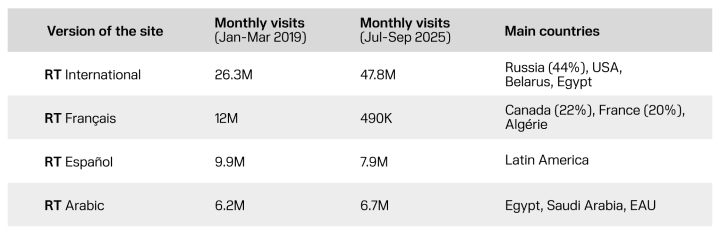

Using the website traffic analysis tool SimilarWeb for July–September 2025 and comparing it with the figures from March–May 2019 noted by Audinet, we can determine how RT’s audiences have evolved.

We can see a significant increase for the English-language website (which also includes the Russian-language version), rising from 26.3 million to 47.8 million visits between 2018 and 2025. In contrast, the French website saw its traffic drop more than twentyfold due to the ban. The decline is smaller for the Spanish site but still notable, likely reflecting the loss of its audience in Spain after sanctions, with a decrease of about 2 million visitors. RT Arabic grew slightly—from 6.2 million to 6.7 million—showing that the site remains visited even after losing much of its Arabic-speaking audience in Europe.

UNITED24 Media research also identified several active mirror sites still distributing RT content and analyzed their recent traffic in Europe, where RT is banned. Between July and September 2025, Swen**.site—a mirror of RT International—drew between 261,000 and 309,000 monthly visits, mostly from Sweden. Freed**.online, a mirror of RT DE, recorded between 646,000 and 690,000 monthly visits over the same period, almost entirely from Germany. This made it the 3,701st most visited website in the country, a notable position relative to a population of 83 million.

Countering RT’s global information war

Researchers, policymakers, media experts, and journalists have examined RT’s global footprint and the tools available to states to counter its destabilization strategies.

The Institute for Strategic Dialogue conducted an audit of European measures to protect against Russia’s media warfare in Europe. The report says the European Commission and Member States should strengthen their legal, technical, and monitoring frameworks under the Digital Services Act (DSA) and the European Democracy Shield by:

Monitoring Kremlin-affiliated media in cooperation with civil society, to track their online activity and the narratives they disseminate;

Establishing a public list of mirror sites linked to sanctioned entities to enable real-time blocking, while upholding freedom of expression standards by including appeal and redress mechanisms.

History offers precedents for prosecuting propagandists who abetted crimes of aggression. At the Nuremberg trials, two Nazi figures—Julius Streicher and Hans Fritzsche—were tried for incitement and for their roles in the German government’s propaganda. In Rwanda, several leaders of Radio Télévision Libre des Mille Collines, which called for the murder of Tutsis, were also convicted.

Russian propagandists at RT have fanned the flames of war, lying and engaged in genocidal rhetoric against Ukrainians:

Russian presenter Anton Krasovsky called on RT for Ukrainian children to be burned and drowned.

RT editor-in-chief Margarita Simonyan declared, “All our hope is in famine,” alluding to choking off global wheat shipments from the Black Sea.

Moscow violates Article II of the Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide. Russian media members are complicit with sections B, C, and E of Article II of the convention.

Julian McBride

American journalist

The French Institut of Insternational Relationships (IFRI) noted on November 4: “Considered potentially comparable to the effects of a large-scale troop deployment, the psycho-informational impact is not limited to opportunistic manipulation or disinformation operations, but aims to transform individuals and societies in the long term — on both the emotional and psychological levels.”

Awareness must now be matched by the implementation of means to defend against this form of warfare — already unfolding, yet still unnamed.

Russian propagandists such as Xenia Fedorova, Afshin Rattansi, and Dinara Toktosunova remain unsanctioned, continuing to wage the Kremlin’s global information war.

-29ed98e0f248ee005bb84bfbf7f30adf.jpg)

-24deccd511006ba79cfc4d798c6c2ef5.jpeg)

-29a1a43aba23f9bb779a1ac8b98d2121.jpeg)

-4d7e1a09104a941b31a4d276db398e16.jpg)

-46f6afa2f66d31ff3df8ea1a8f5524ec.jpg)

-3db1bc74567c5c9e68bb9e41adba3ca6.png)