- Category

- Life in Ukraine

Ukrainian Children Return to Classrooms in the Shadow of War

A new school year has begun in Ukraine, once again under the shadow of Russia’s full-scale invasion. Despite frequent air raid alerts and the constant threat from Russian attacks, city administrations, schools, and teachers across the country are finding ways to ensure that as many children as possible can continue their education.

Back to a rebuilt school

It’s almost 10 AM, and the schoolyard of the Mykhailo-Kotsiubynsky Lyceum in the Chernihiv region is packed with pupils, parents, teachers, and even village residents. Everyone has gathered here for the first day of the new academic year. This time it is particularly special: the fully renovated Lyceum is finally reopening its doors after being heavily damaged in a Russian missile attack on March 4, 2022. But before the official ceremony has a chance to begin, an air raid alarm sounds, sending everyone down to the bomb shelter.

“I was here, in Mykhailo-Kotsiubynsky, when everything happened,” recalls Dariia, an 11th grader. “I live close to the school and so I even heard the moment of the attack. I saw the school after the Russian troops left our village.” We sit talking in the hallway of the newly renovated building.

“It’s a great feeling to be spending my final year at school in such a beautiful, renovated building,” she continues. “It’s inspiring and gives me more motivation to study. We spent a lot of time at home doing distance learning or in a mixed format. Even when we did come to school, we often spent more time in the shelter than in the classroom.”

The town of Mykhailo-Kotsiubynske was under Russian occupation for 33 days. Alina, another pupil, tells me that seeing the destroyed school was difficult for her. “You see how the future potential is being destroyed. You see how the place where you studied, where you were brought up, where you gained something new, where you developed, where you improved, is ruined. And this really affects your personality”. Now studying in 9th grade, Alina has already decided that she wants to be an architect. Primarily, to fulfill her dream of transforming her hometown into something much bigger and better.

When the Russian missile hit the school, between 100-130 people—including children—were in the shelter. In one room of the school, the principal shows me missile fragments that were left behind, as well as a clock that once hung on the wall. It stopped on the day of the attack. Soon, the principal tells me, this room will be converted into a museum.

Mykola Shpak has worked in the lyceum since 1993. For the last 10 years, he has been the principal of the school. “I was born in this village and graduated from this school. My parents worked in this school. My children studied here. My wife works here. Therefore, my entire life is closely tied to my native school. Imagine if your native house was destroyed. How would you feel?”

It’s difficult to imagine what the damage was like when you see this newly renovated building, painted in bright colors. “A lot of work has been done; all these renovations took almost a whole year,” Shpak explains, showing me around the elementary wing. “There were no doors, no windows, and the interiors of the classrooms were also completely destroyed.” Some whiteboards still bear traces of the Russian attack—holes from missile shrapnel.

But it was a different part of the building that suffered the most damage. “There was a direct missile strike, which not only destroyed everything from the attic room to the basement, but also the physics, chemistry, and computer science classrooms. Everything the children needed for learning and all the equipment that was stored there.” Now, standing in the big and bright room in the modernized facility, he can only point to where the floor and walls were once missing.

“It was not only about restoring part of the building—it also included thermal modernization, namely insulation, the replacement of the heating system, the renovation of all interior spaces, and the inclusion of accessibility features, such as the construction of ramps.”

Funds for the upgrades to the lyceum were gathered by UNITED24 along with two of its ambassadors—world-renowned footballers Andriy Shevchenko and Oleksandr Zinchenko. They both visited the educational facility on May 31, 2023, witnessed the destruction, and even played a game of football with the pupils. In August 2023, they played together again—this time in London, where The Game4Ukraine at Chelsea’s Stamford Bridge aimed to raise money to rebuild the school in the Chernihiv region.

“Because of COVID and then the war, we never really got to experience normal school life,” says Natalia, a 10th-grader, smiling. “I’m so excited to sit at a desk tomorrow.”

Learning underground

For many Ukrainian children, a return to regular classrooms is still impossible. Certain regions are still too dangerous due to constant Russian attacks. To get more pupils back into the classroom, Ukraine started to build schools underground.

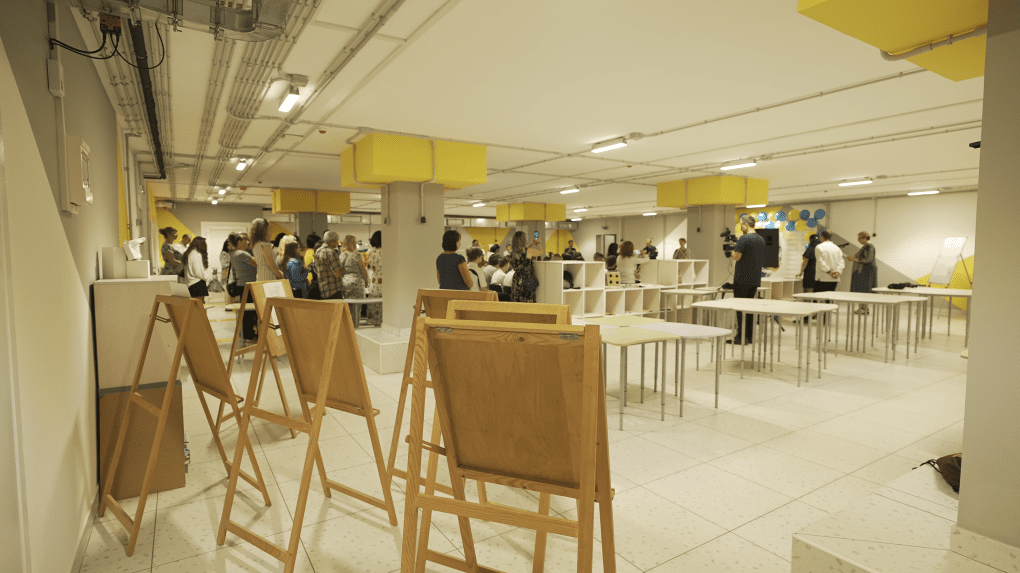

Kharkiv was one of the first cities to look for novel ways to get pupils back to their desks. In 2023, the government introduced a seemingly unconventional solution—setting up classrooms in metro stations, which are commonly used as shelters. Until now, these “metro schools” still operate in six locations across the city.

However, this was insufficient for one million inhabitants, so in April 2024, the first underground school appeared. As of now, seven such educational facilities are operating in the city, with three of them opening on September 1, 2025.

Shortly after the first underground school was constructed in Kharkiv, another was also opened in the town of Liubotyn in the Kharkiv region. In addition to offering the highest level of security, it featured heating, ventilation, a water supply system, a diesel generator to safeguard against power outages, and an elevator for accessibility. Back then, the UNITED24 Media team had the opportunity to see it firsthand.

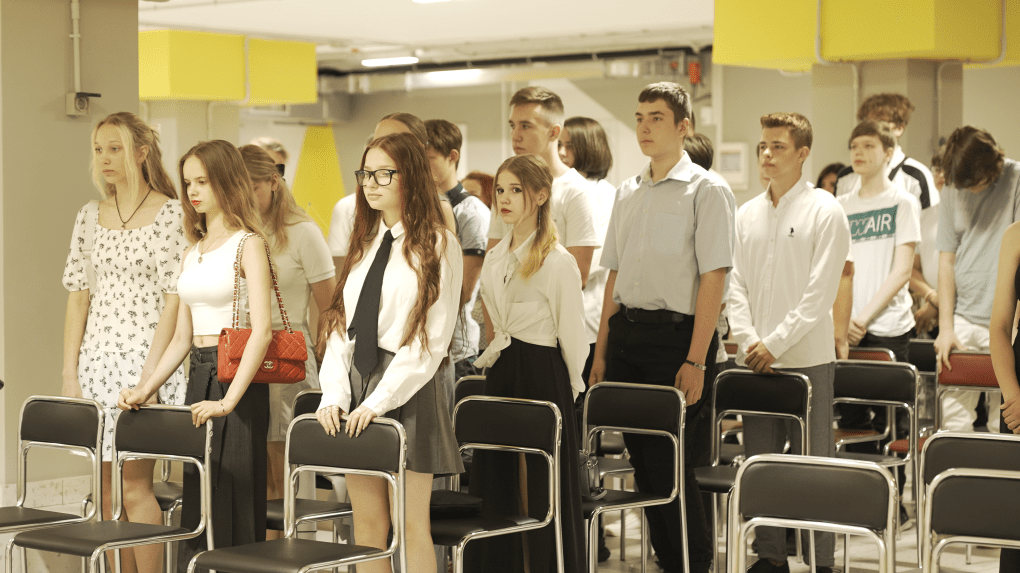

The day it opened was also the day many pupils met each other for the first time since the beginning of the full-scale invasion. One pupil, Liza, told me about her last day at school: “I went there at six in the morning, when nothing was clear. As soon as I got on the train, I was told that there was war. So I came to school, took all my things from the dormitory, and was taken home.” Her classmate Sofiia added that some of her school friends went abroad. “We communicated in Telegram chats, but that’s not the same”.

Such safe environments allow pupils not only to learn, but also to meet their friends. “Communication is essential”, stressed the school principal. “Teachers have their own difficulties in conducting distance learning, but it’s even more difficult for the children and parents. So when we all saw each other and had some classes, there was an emotion that could not be expressed. ”

While there was only one such facility in the Kharkiv region last year, by the end of 2025, an additional 38 underground schools are planned for completion, according to the head of the Kharkiv Regional Military Administration.

As of now, underground schools are already operating or under construction not only in Kharkiv, but also in the Zaporizhzhia, Kherson, Sumy, Dnipropetrovsk, Mykolaiv, and Chernihiv regions. These are areas where traditional shelters are not sufficiently safe. According to the Minister of Education and Science, a total of 150 underground schools are expected to be opened by the end of the year, allowing children to return to in-person learning.

During the last academic year, for example, between 100,000 and 150,000 pupils switched from remote to in-person learning, in particular, because children had the chance to study in these underground schools. However, the Minister acknowledged that it is currently impossible to provide access to offline education for all Ukrainian children.

Learning at a distance

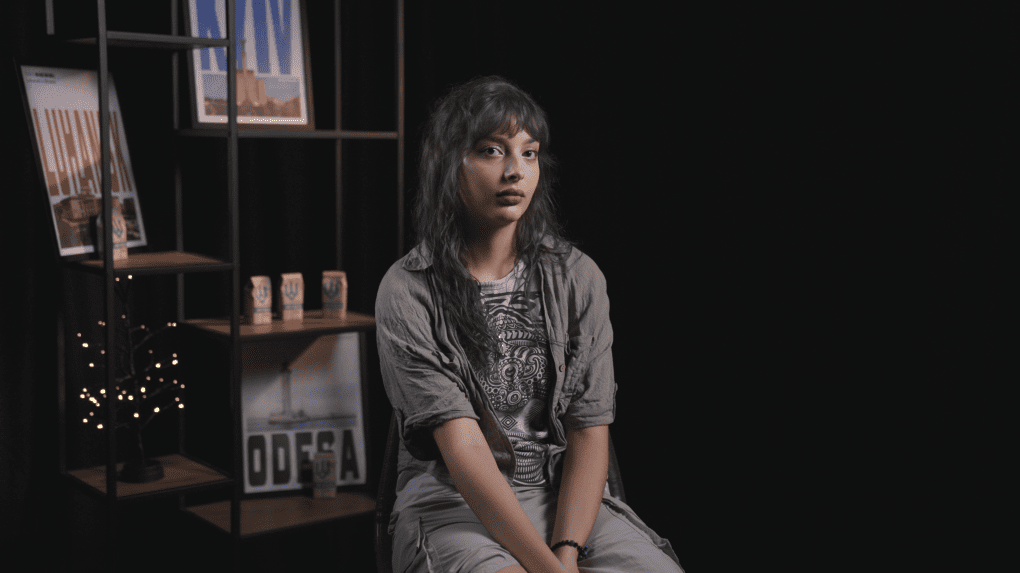

For Marta, distance learning was the only option to receive a Ukrainian education. Just a few months ago, she was still living in temporarily-occupied Donetsk, where she had started university, and waited for her 18th birthday to flee to Kyiv.

“I secretly enrolled in a Ukrainian school,” she recalled. “I completed all the homework and final tests in different disciplines.” Back when she was still in Donetsk, Marta finished all the required assignments to receive her certificate for finishing 9th grade. Later, in Kyiv, she fulfilled the requirements for completing 10th and 11th grade. After that, she took the National Multi-Subject Test to enter the university in Kyiv.

“I couldn’t take part in the online classes [during her distance learning—ed.], but I did everything else,” Marta told me. Her determination reflects the scale of the challenge: according to the Ministry of Education and Science, in 2024/25, Ukraine had nearly 3.74 million pupils. Of them, around 391,000 studied remotely inside Ukraine, 364,000 combined studying abroad with Ukrainian distance learning, and more than 42,000 in occupied territories continued remotely with Ukrainian schools.

The first day of school

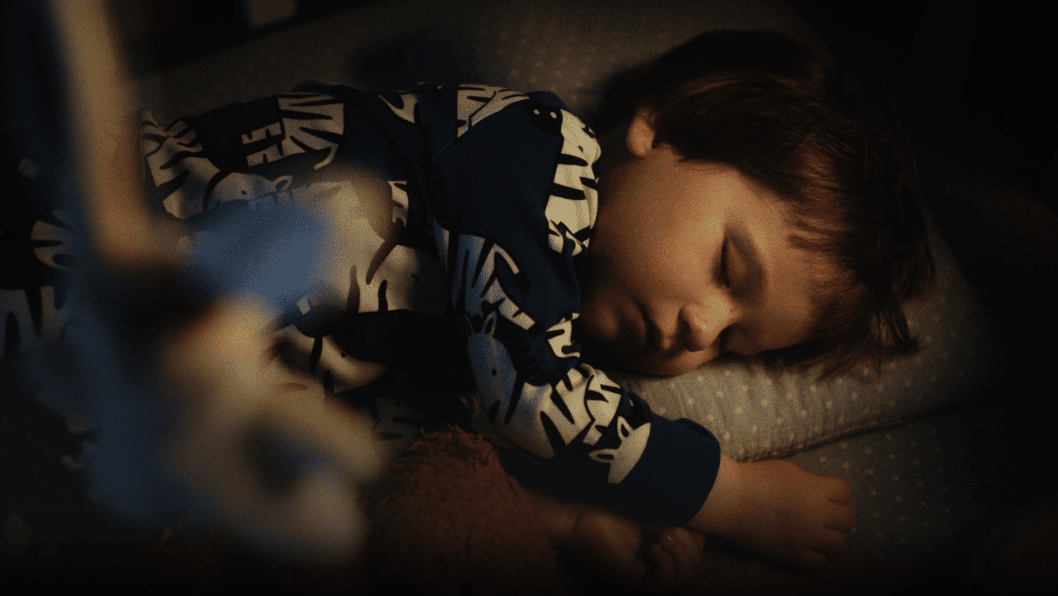

Meanwhile, the school bell in the Mykhailo-Kotsybynsky Lyceum signals that the air raid is over. Everyone gathers in the schoolyard—once again. The 11th graders—those who will be bidding farewell to these walls in a year—take the hands of first-graders, who still have a lot of time here ahead of them.

“I remember the first days when the occupation ended,” the principal tells me. “The children had been isolated for a month; everyone was sitting at home, hiding in the basements, and so on. When they returned to school, the first thing they did was hug everyone. They came and hugged the teachers, even ones they didn't get along with.”

A small girl rings the bell to mark the start of the school year. Shpak looks at the school, then adds: “Children need live communication and live learning. No distance education can fully replace that.”

-73e9c0fd8873a094288a7552f3ac2ab4.jpg)

-9a7d8b44d7609033dbc5a7a75b1a734e.jpeg)

-554f0711f15a880af68b2550a739eee4.jpg)

-6ead6a9dd508115a5d69759e48e3cad1.jpg)

-29a1a43aba23f9bb779a1ac8b98d2121.jpeg)