- Category

- Life in Ukraine

Inside Ukraine’s DNA Search Reuniting Fallen Heroes With Their Families

Ukraine received the remains of 6,057 fallen soldiers in June 2025—the largest return of bodies since the full-scale Russian invasion began. Many arrived without names, just numbers. Behind each one may be a family, still waiting and hoping. Across the country, DNA specialists are racing against time to restore identities.

In Kyiv, we visited one of Ukraine’s full-profile DNA labs to see how experts handle the most complex cases.

“It’s absurd, but we are lucky”

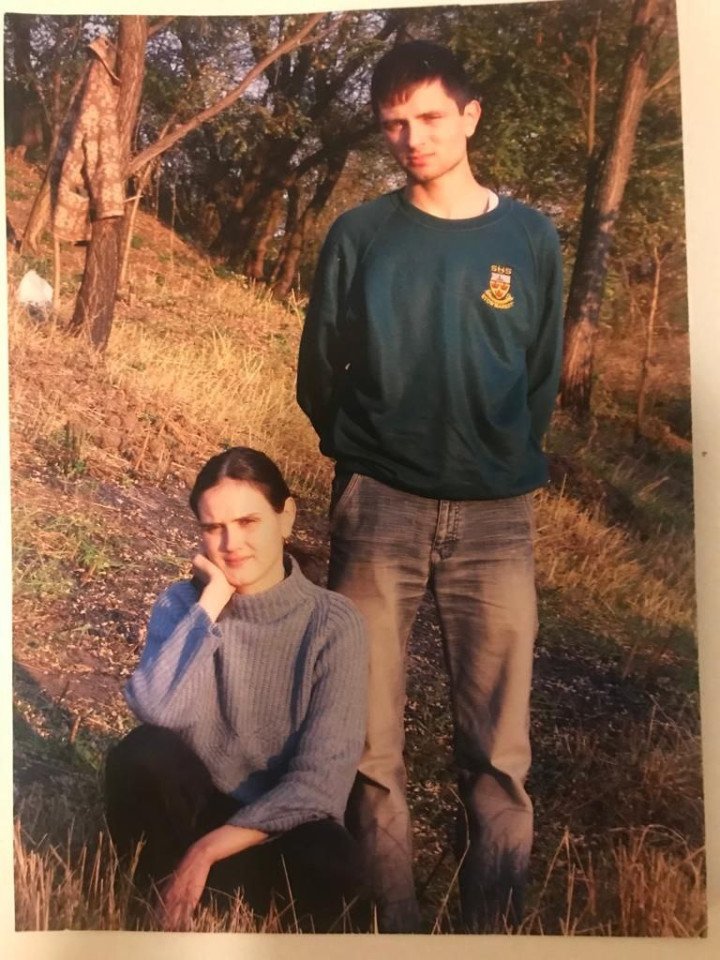

Behind every DNA search, there’s often a family waiting for answers. One late evening over Zoom, we speak to Hanna. Her younger brother—Kostiantyn, 38—was killed in action in Bakhmut in May 2023, but was considered missing for almost a year—until forensics matched his DNA. Hanna pauses mid-conversation to wipe away tears, a box of napkins close to hand.

She recalled the post on Facebook she saw another day—about women who believe they were “lucky”: “They say, ‘We are lucky. He went missing in action, and we still have hope,’ Or ‘We are lucky. They returned his body from captivity. We knew that he died, but now we have clarity.’”

On Sunday, May 14, 2023, Kostiantyn’s family realized that he was missing in action. “He would always call or text every three days. That Sunday—was the fourth day,” Hanna remembered. “It was Mother’s Day, and he would always go out of his way to greet me because he had great respect for the role of a mother. The fact that he didn’t call, didn’t write anything… something inside me already knew something was wrong.”

Hanna spoke to her brother not long before. “He was in Kostiantynivka at the time,” she says. “Talking about how lush and green the grass was, compared to Bakhmut, where there was no grass left. Everything was burned because of the shelling.”

At that time, Hanna and her three daughters—Kostiantyn’s nieces—were living in Finland. They were forced to flee Kharkiv after the beginning of Russia’s full-scale invasion.

“Literally three days later [after Kostiantyn was missing—ed.], our dad was called to collect his DNA,” she said. However, Hanna tried to believe that her younger brother may still be alive.

“Maybe he’d been taken prisoner, maybe he’d somehow gotten out,” she remembered telling herself. “Then I was at the Lavra church , where the priests offer memorial prayers for those with loved ones at war. I didn’t know what kind of note to write—for good health or for his soul to rest in peace.”

For a long time, there was no news. “Everyone kept saying we’d find something out once our forces liberated Bakhmut,” Hanna said. “But no one knew when that would be.”

In April 2024, Hanna received a call from their father. “‘The DNA was a match. We’re going to bury our Kostia.' That was incredibly painful.”

Kostiantyn started his military service in the spring of 2014, after participating in the Revolution of Dignity . He fought near Mariupol and took part in the Shyrokyne standoff . Even after a prolonged rehabilitation following a car accident, he chose to remain in the ranks.

It wasn’t until 2021 that he decided to return to civilian life—a plan abruptly upended by Russia’s full-scale invasion on February 24, 2022. In response, Kostiantyn joined the 127th Kharkiv Territorial Defense Brigade. He was killed in action on May 14, 2023.

“He wanted to be a hero, and he was,” Hanna says. “When they were attacked, he had run into the entrance of a high-rise building, dragging another guy in after him.” Kostiantyn was born and raised in Kharkiv’s largest residential district. “He was a child of Saltivka—raised in high-rise buildings. He died in a high-rise.”

Returning to the post about “lucky women,” Anna stresses: “A part of me thinks it’s absurd to consider us ‘lucky’, but another part says: ‘We are lucky. He came back to us. Of the five who were in the group—he was the only one who returned.”

Ukraine’s DNA identification labs

The first thing we need to do before being allowed in the DNA-laboratory is put on protective clothing—a gown, shoe covers, a mask, and a cap. This procedure is in order “not to contaminate the biological material that will be studied with our own biological material,” explains Ruslan Abbasov, Deputy Director of the State Scientific Research Forensic Center of Ukraine’s Internal Affairs Ministry. He explains the whole process to us.

Extremely challenging samples

“If at the beginning of the year we had a workload of about 15,000 samples, which had accumulated over time, then as of today, we are conducting more examinations than new samples are coming in,” Abbasov says. “This is a positive trend in terms of the waiting time for close relatives. We have reduced this time as much as possible.”

There are various state agencies involved in forensic analyses. Within the Ministry of Internal Affairs, there is the MIA Expert Service branch, with 25 institutions. Among those 25, 20 are equipped with functioning full-profile DNA laboratories.

“The research here ranges from analysing simple samples of living individuals to more complex cases,” says Abbasov. “It includes bone fragments, teeth, and biological material from repatriated bodies. These samples are considered extremely challenging. Firstly, because of the condition in which they were received, and of course, the sheer quantity of fragments.”

When examining samples—including those from repatriated bodies—experts analyze numerous specimens from each fragment, says Abbasov. “That can be 10 thousand per month.” In practice, however, he adds that fragments often belong to the same individual. “We can analyze between 7,000 and 10,000 fragments, but in the end—after about a month—we end up with just over a thousand DNA profiles of bodies that are still unidentified.”

“Do you often receive bone fragments?” we ask Abbasov, standing next to a station where an expert is removing all the remnants to work with bone tissue. “Mostly bone fragments, because nothing else is left,” he answers.

From belongings to bone

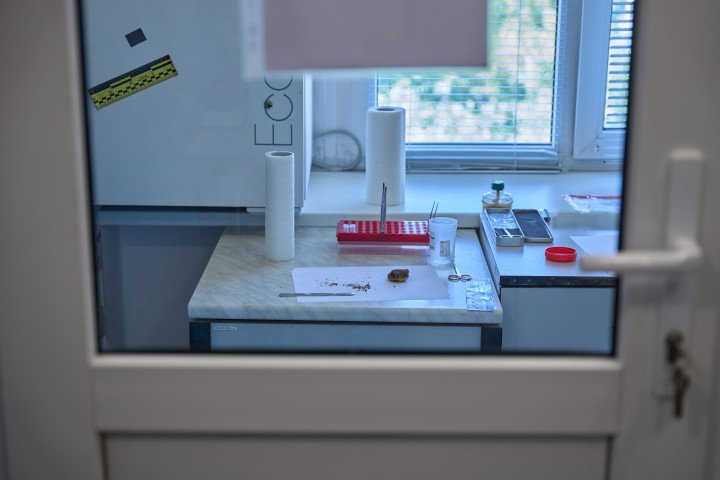

The lab is divided into different zones—each serving a specific purpose. Even though we are wearing protective gear, we can only witness the processes through a window from the corridor. Only authorized personnel can access the samples. In one of the rooms, an expert opens some packing. Inside is a razor.

“When there are no close relatives, personal belongings are collected and sent for analysis,” says Abbasov. “We take a swab from the items.” The expert places the razor on the table—next to a special ruler. The first step is the examination, which includes photography and documentation.

As soon as it’s done, the expert takes a cotton swab, moistens it with deionized water, and cleans the working surface of the razor. Abbasov explains: “It’s where the blade is, where fragments of epithelium or hair might be—because there’s no DNA in the cut hair itself, but there will be some in the epidermis, in the tiny bits of skin. The surface is thoroughly cleaned, a piece is cut off, and it’s placed into a single-use tube.”

We head to the next zone, where another expert is working on a fragment of bone. Abbasov comments on every move behind the glass:

“To work with bone tissue, all remnants of other tissues must first be cleaned. Now he’s about to begin drilling. There is an autopsy saw available, in case a piece needs to be cut. He labels and marks which fragment it belongs to, then places it in a rack. He does the same with dozens, even hundreds of samples.”

So, how do they extract a DNA profile? The next stage for the samples is lysis, which aims to extract DNA from the cell’s nucleus. Depending on the sample—whether from a living person or a repatriated body—the process can take several hours or several days. Special equipment makes it possible to analyze 100–200 samples within a 24-hour period.

Once the samples are ready, they move on to the final stage. “When we have worked with the samples to extract DNA, we also need to determine whether DNA is even present, and in what condition,” explains Abbasov.

The only room we are permitted to enter is packed with technical equipment—mostly genetic analyzers. “They vary in throughput capacities—from eight DNA profiles in 40 minutes to 24 DNA profiles in 40 minutes,” he says. What does this provide? “It allows us to work simultaneously with a large number of DNA profiles,” says Abbasov. “Just a few of these genetic analyzers can process about 200 DNA profiles per day and produce genetic data.” The data will then be analyzed by forensic experts.

All the DNA profiles are entered into the electronic State Registry of Human Genomic Information to enable automated searches for identifying familial relationships. When a DNA profile is checked against the electronic registry, a match is automatically catalogued.

But what happens if there are no matches—or if the DNA profile cannot be established? “The DNA profile is placed into the electronic registry, and a match may occur over time. If it isn’t possible to establish a DNA profile, the expert returns a second or third time to make another attempt until a profile is successfully obtained.”

Experts currently analyze 24–27 loci per sample, says Abbasov. This allows results to be compared with those obtained abroad, since that number of loci ensures compatibility regardless of which laboratory established the DNA profile—whether it was done in the Expert Service’s laboratory or in a facility overseas.

Practice of collecting samples

Ukraine’s practice of collecting samples from close relatives started back in 2014—when the Anti-Terrorist Operation began, says Abbasov. However, with the Russian full-scale invasion, the process has been scaled up, and also has become much more accessible.

“In 2022, there were nine full-profile DNA laboratories,” he says. “It seemed sufficient at the time, but by the following year, we realized that it only seemed that way. Even from a purely logistical standpoint, it was difficult for a family to travel from one region to another just to provide a sample. By the end of 2022, we ensured that all citizens had access to this service.” The number of geneticists has also increased—from 170-180 personnel before 2022 to 450 today.

Now, receiving around 6,000 samples from relatives per month, the experts are trying to complete the analysis within one month. “Previously, we were focused on handling the volume, whereas today we can analyze a single sample applying multiple methods—two, three, or more if needed. We have the capability to study a sample in depth.”

This DNA laboratory, in particular, is the only one in the country with the capacity to provide mitochondrial DNA analysis. “If identification is needed through the maternal line—for example, only the maternal grandmother is available, the mother is deceased, and the person is missing, this type of analysis is conducted using specialized equipment.”

For relatives, if they want to provide a sample, everything starts with requesting the pre-trial investigation authorities. “After registering a report of a missing person or another tragic event, biological samples are collected from the relatives. These samples are then used to appoint a forensic molecular genetic examination at any forensic institution. The DNA profile is established, analyzed, and entered into the electronic State Registry of Human Genomic Information.”

When a match is found in the system—it is formally identified and documented. An official letter is then prepared and sent to four recipients: the investigator handling the relative’s sample, the investigator handling the repatriated body’s sample, the Main Investigative Department, and the Office for Missing Persons under Special Circumstances. “In addition to confirming the match, the letter includes recommendations outlining possible scenarios and next steps, as well as different ways to potentially finalize the identification.”

Abbasov stresses that the main goal for these experts is to identify each and every one of the repatriated bodies.

“We cannot stop just because we are tasked with identification, and it’s not working,” says Abbasov. “The number of attempts, why it’s not working, and what needs to be done—these are expert-level issues. At this stage, we do everything we can to obtain the DNA profiles.”

Russia is complicating the process

After Ukraine received over 6,000 bodies of the fallen from the Russian side, the Minister of Internal Affairs Ihor Klymenko stated that Russia is turning the repatriation of fallen soldiers' bodies into a tool of manipulation and pressure. On his Telegram page, he reported that “the bodies are returned in an extremely mutilated state, with body parts in different bags. There are cases when the remains of one person are returned in different stages of repatriation.” Moreover, in the last repatriations Russia handed over the bodies of Russian soldiers mixed with the bodies of Ukrainians, Klymenko added.

In a few days, on June 19, the Minister of Internal Affairs also provided evidence of his words. Among them were photos of Russian soldiers’ documents such as passports and military IDs. “The world sees the difference: while Ukraine brings home every one of its fallen—with a name and with dignity—Russia hides its dead, uses them as disposable material, and then forgets them,” Klymenko underlined.

On June 23, during the press briefing, it was reported that since the beginning of 2025, investigators from the National Police and forensic experts have identified 20 cases of Russian military bodies being transferred during the repatriation process.

-73e9c0fd8873a094288a7552f3ac2ab4.jpg)

-9a7d8b44d7609033dbc5a7a75b1a734e.jpeg)

-554f0711f15a880af68b2550a739eee4.jpg)

-6ead6a9dd508115a5d69759e48e3cad1.jpg)

-29a1a43aba23f9bb779a1ac8b98d2121.jpeg)