- Category

- Life in Ukraine

They Rebuild Faces of Ukrainian Soldiers Scarred by Russia’s War—Inside the Operating Rooms

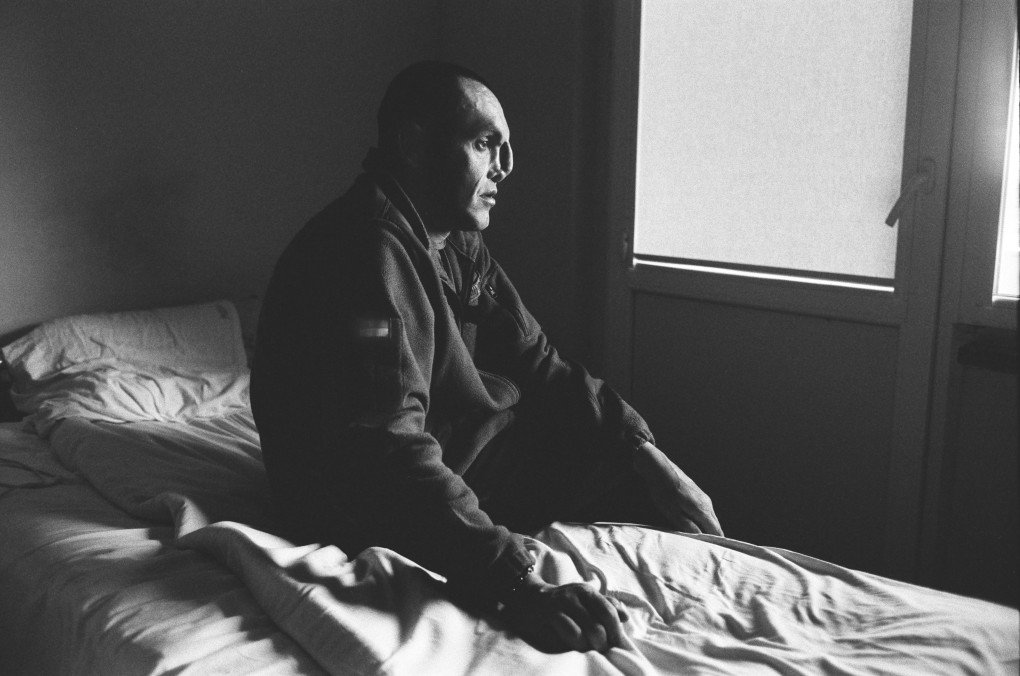

We enter the hospital room to meet one of the patients. Before we know it, we’re talking to everyone in the room. They’re all soldiers here, injured on the front line. “You can take a photo of me, but I won’t be able to tell you anything. I don’t remember,” says 23-year-old Serhii. The next day, he’ll be among the first called in for surgery, performed by “Face the Future” Medical mission.

On Tuesday morning, around 9 a.m., the entire staff gathers in the hallway of a hospital department in Ivano-Frankivsk. Among the Ukrainian workers are Canadians and Americans, who together will help more than 30 patients over the next few days—both military and civilians, who have suffered severe mine and blast injuries to the face and neck.

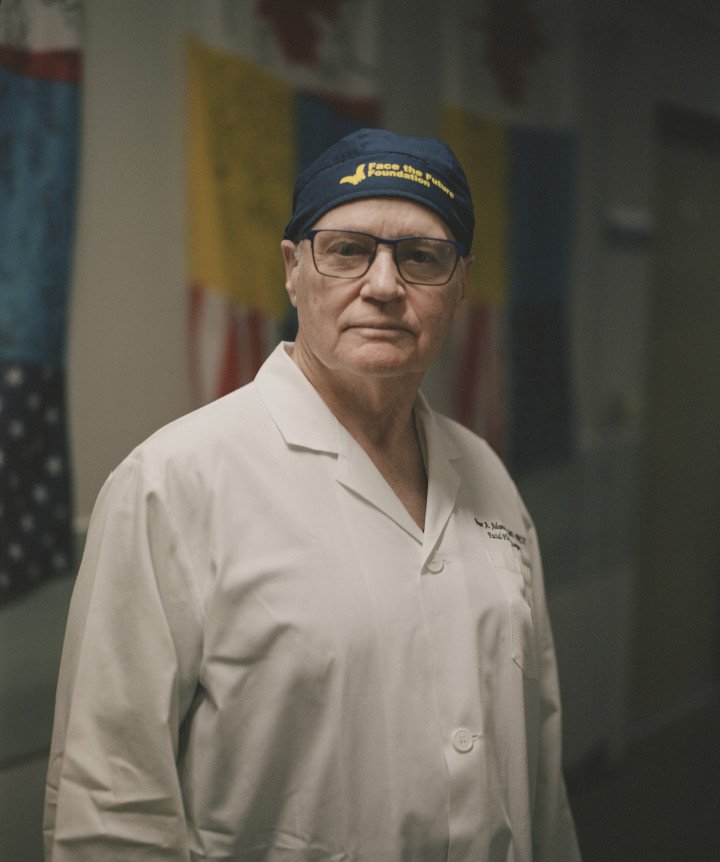

But now, in this hallway, everything begins with a minute of silence—for all those who gave their lives for Ukraine's future. “We are all unified here today in order that we can provide the best possible care for our Ukrainian soldiers,” says Peter Adamson, the founder of the Face the Future Foundation. “They are our soldiers as well as your soldiers, because they are protecting the values and the ideals that we uphold as well.” In just a few minutes, the first surgeries will begin.

The hospital room

"You can see how I look with a beard. That's why the guys from Zhytomyr nicknamed me that, and it stuck," says Artem Korchak from Odesa, explaining the origin of his call-sign “Batiushka”—a familiar term for an Orthodox priest, roughly equivalent to calling someone Father. Artem, however, has no connection to the clergy, only ever meeting church workers in civilian life. Before Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine, he worked in a funeral parlor.

"I served in the 25th 'Sicheslav' Separate Airborne Brigade, trained in England, then in Germany," says Artem. "When I joined the military, I was a machine gunner, a grenade launcher operator, and a medic." Batiushka started his service in the summer of 2022. He says he wanted to join as early as February, but at the time, he wasn’t accepted because he had no military experience.

Eventually, after joining his brigade, he served across the Donetsk, Luhansk, and Kharkiv regions. On February 5, 2023—around 2 a.m.—Artem was wounded. “I had just come off duty from the observation post. Went to my ‘spot.’ Only a few moments later—and then only light, nothing else. I thought about my wife and child… But then, in that light, I understood that nothing worried me anymore. And then—darkness and pain. Hellish pain.”

We bring you stories from the ground. Your support keeps our team in the field.

A 120mm mine hit the trench where Artem was with his comrade. “As I always said, Russian ‘Ivan’ had a couple of shots of vodka, so the mine landed directly in the trench. He was lucky,” Batiushka laughs.

As his comrade was concussed, Batiushka had to call for reinforcements from other positions. Artem was dragged three and a half kilometers to the evacuation vehicle. When they were almost at the evac point, another mine exploded. Everyone was concussed.

For Artem, this was his second injury—the first occurred when he went deaf in both ears during a Russian drone attack. However, doctors in Kharkiv managed to restore his hearing. “Being blind is worse than being deaf,” says Artem. “A deaf person can still see, you can write to anyone. But a blind person… Unfortunately, one of my eyes will never see again.”

Artem waited to be admitted to the mission for about six months, saying all administrative duties were handled by his wife. Meanwhile, he asks her not to come to the hospital to see him. After being examined by the Face the Future mission’s surgeons, Artem says: “They offered a few options. They want to fix this defect.” He pointed to the hole on his face, covered with a bandage—he lost part of the bone there. “Most likely they’ll break my nose. Nature doesn’t like emptiness; when the hole appeared, it healed over. They also offered to lift my eye. You see, it’s sunken.”

On the bed next to Artem’s is Vadym Korsun. Originally from Khmelnytskyi, he was drafted and joined the 82nd Brigade. In 2023, Russian troops injured him in the Zaporizhzhia region.

“We were driving, then there was a hit. I was in the ICU for four days in Zaporizhzhia.” This is already the third surgery the mission will provide for him. After being treated in Chernivtsi, Vadym was referred to foreign surgeons.

“This spring, they took cartilage from another rib, implanted it, and also took skin from my head. Now, they’ll be removing the excess tissue,” Vadym says. In the hallway, he runs into one of the doctors. The medic tells him that his surgery will be later in the evening, after the more complicated cases are finished.

Further down the hallway is another room. On one of the beds, 22-year-old Mykhailo from Volyn—the youngest of three children—is expecting us. He had signed a contract to serve in the army at the end of October 2021. Just a few months later, Russia launched its full-scale invasion, and Mykhailo has been fighting ever since, including in the defense of the Kharkiv and Donetsk regions.

“On the morning of March 19, the assaults began,” says Mykhailo. “They [the Russians—ed.] took two dugouts. We needed to move closer, literally 300–400 meters, but we didn’t make it. A 120mm mortar round landed, and a fragment hit me.” Wounded, he searched for a way to survive.

“I walked across the field injured from 4 to 9 p.m. Logically, since I was wounded while moving forward, I should have turned around and gone back. Several FPVs flew in, but my memory of that moment is gone. By evening, I blacked out—I fell asleep. I woke up to pitch-black night. Where to go? What to do? I kept walking across the field shouting ‘Foma,’ calling for my comrade. If it weren’t for him, I wouldn’t be sitting here. I crawled over to them—and it took us another two days to get out.”

Next to Mykhailo are his girlfriend and his mother. As he describes what happened to him, they cannot hold back their tears. After that day in March, he was unable to reach them for two weeks. His first surgery was in Sumy, where, as he says, doctors “put my head back together and cleaned everything up.” Then he went to a hospital in Kyiv and, finally, to Ivano-Frankivsk. Doctors replaced the lens to restore vision in at least one eye and implanted a titanium plate in his forehead.

Now comes the next stage—with the help of the mission’s surgeons—to prepare his second eye for a prosthesis. “They won’t place it yet. They’ll clean everything and stitch it up, and it will need a month to heal before the prosthesis.”

Mykhailo says that from the very beginning, it was difficult to grasp what had happened to him. But he adds, “What happened, happened. The main thing is that I’m on my feet and in my right mind.”

Preparing the mission

“Face the Future Foundation began in 1996, so this coming year, we're going to have our 30th anniversary,” its founder, Peter Adamson, says. With decades of experience in plastic surgery, he is a professor and former head of the Division of Facial Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery in the Department of Otolaryngology—Head and Neck Surgery at the University of Toronto. This is already the 62nd mission for the Foundation—and the 6th in Ukraine. At the same time, it’s the first time their medics are working in a country that is currently at war.

“We're not on the front lines, but by helping soldiers, we respect the integrity and the duty that they are serving, not only to Ukraine, but they really are protecting all of our Western liberal democratic values,” Dr. Adamson stresses. Each mission visit is carefully prepared. The work begins many months before the surgeries are performed—all because of the complexity of the cases the surgeons have to deal with. “We're seeing patients, soldiers, who come to us who've lost the bone structure of their face. In many cases, they've also lost the soft tissue. And in too many cases, they've also lost organs such as their nose, their eyes, sometimes even being blind in both eyes.”

Usually, a single specialist cannot handle such injuries. That’s why several surgeons from different fields often take part in one operation—each performing their part of the work to help the patients as effectively as possible. “We find on average many of the soldiers need at least two, three, four, sometimes even five different procedures. So although we're only operating on 30 to 35 patients, we're going to perform probably close to 100 procedures altogether during the week.”

“Some of the cases may take up to 10-11 hours,” Nataliia Komashko adds. An otolaryngologist at the Ivano-Frankivsk Regional Clinical Hospital, she also serves as the mission director for the Face the Future Medical mission from the Ukrainian side. Dr. Komashko explains that, because the preparation process is quite lengthy, patient selection continues throughout the year.

“Some of the patients need a patient-specific implant, and it took us three or four months [to get them—ed.],” says Komashko. “Some of the patients need another step, and we can manage the steps by ourselves. Every week, we have a Zoom call with our colleagues—we decide what we do with the patient, what's the next step for the patient.” She says it usually takes half a year to prepare one mission.

“We live from one mission to the next. We cannot stop”, she sums up. The team of foreign medics may vary—this time the mission included seven surgeons, nine nurses, and two anesthesiologists from Canada and the US.

Another major focus during such missions is education—the foreign specialists share their knowledge with Ukrainian colleagues, particularly through symposia and courses.

The surgery

A nurse from the mission enters the room and hands Serhii—the 23-year-old we mentioned in the intro—a small bottle. “The doctor asked you to wash your face with this,” she says to him. Serhii does not speak English, so her words are translated. In a few minutes, the young man will be taken in for surgery, which will last for the next 5–6 hours.

Among the specialists who will be treating Serhii in the operating room is Raymond Cho, an oculoplastic surgeon from The Ohio State University in Columbus. “[We have—ed.] a soldier who sustained severe injuries to his cranium and his face, and he also lost his left eye. He lost a large piece of bone from the rim of the eye socket, and also a large fracture of the floor of the eye socket. He has a deformity of the upper eyelid as well.” All of this refers to Serhii. This is exactly the kind of case where surgeons from different specialties take turns in the operating room, as the patient requires multiple procedures.

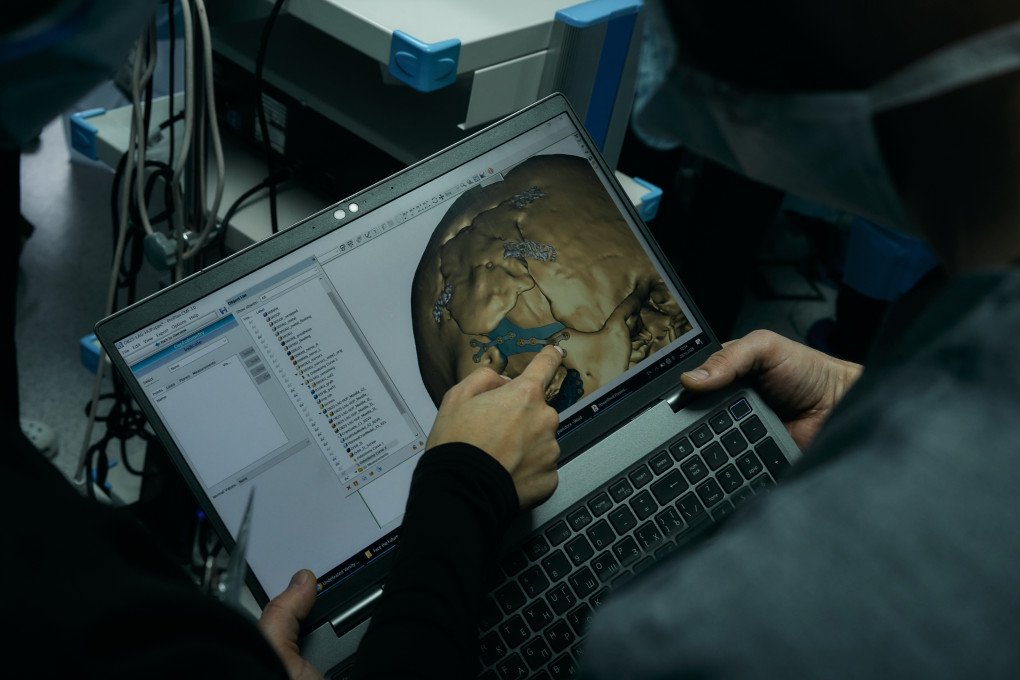

“We're reconstructing the orbital rim with a bone graft that we're taking from his skull. We are reconstructing the orbital floor fracture with a patient-specific titanium implant that was made for us by ‘Materialise’. And we're also reconstructing the upper eyelid deformity so that he is better able to wear an ocular prosthesis,” Dr. Cho explains.

For Cho, this is already his fourth visit to Ukraine. His first was in the spring of 2023, when he attended the inaugural Face the Future mission in this country.

“When Face the Future was planning its first surgical mission to Ukraine,” says Dr. Cho, “They started to collect patients, review their histories, and their CT scans, and they realized pretty early on that they were going to need an oculoplastic surgeon to join the team. I saw that there was a need, and I responded to Peter Adamson, and we talked for a little bit, and he decided that I would be a good fit for the mission.”

Dr. Cho has considerable experience with combat injuries, having served as an active-duty physician in the US Army for more than 20 years. In particular, he spent six months in Iraq in 2005–2006, and afterward worked in military medical centers for the treatment of wounded service members. He notes that the injuries he sees in Ukrainian servicemen are somewhat similar to what he has dealt with before, but there are also differences.

“The patients that I worked on in Iraq were very recent injuries, in some cases just a few hours old. When I was in San Antonio and at Walter Reed , there were a lot of secondary reconstructions. A lot of patients had been injured a few weeks or a few months earlier. Here in Ukraine, some of them are maybe three to six months. Some of them are even longer—at least a year or more from their injury.” The surgeon explains that as time passes, the work becomes increasingly complex, particularly due to scarring. “Sometimes bones have been fractured, and if they were not initially repositioned, then you have to re-break the bones or find some other way to reconstruct their face.”

While the surgery is ongoing, Roman Lukianov is nearby—a medical engineer from “Materialise,” a Belgian company mentioned earlier by Dr. Cho. He has worked there for 17 years, and for the last year and a half, Roman has served in the Armed Forces as a combat medic. He is here to consult with the surgeons about the 3D-printed implants that were made for the mission.

“We receive CT images,” says Roman. “From them, we create a 3D model, and based on this model, we plan the surgery. Following the plan, we manufacture custom plates, implants, and templates.” For this mission, six implants were needed. One of them—for Serhii.

Meanwhile, the nurses are preparing a recovery room for the patients, where they will be cared for and closely monitored following the surgery. Among them is Carolyn from Canada, who has never been to Ukraine before and, in fact, had no plans to visit in the near future.

“At the last minute, there were some nurses who couldn't come on the trip,” she says. “Three weeks ago, they asked: ‘Would you come?’ I simply said: ‘Yes.’” Carolyn recalls that around 25 years ago, she had already taken part in a humanitarian mission— she spent 3 months in a hospital in Zambia.

She says that working in Ukraine is a small way she can help. “I think what Ukrainian people are going through is more than I can ever put words to,” the nurse adds. “The people are so incredibly welcoming and kind. I feel it's an honour to be here. And yet they feel honoured that we've come.”

The need for a recovery room with constant care stems from the importance of monitoring patients as they recover from surgery due to the effects of anesthesia. Nurses have to check that no one is in pain or having problems with breathing or consciousness—especially since some of the surgeries last around six hours.

There are two anesthesiologists on the team. One of them is Stephen Middleton, also from Canada. He believes, “There's ultimately sort of a moral obligation in a situation like this. Ukraine is not safe, it is in a state of war, and we have a human responsibility to face that and to offer help if we are able to.” The day before the surgeries, he—as well as the other doctors on the mission—saw every patient and did preoperative anesthesia assessments for all of them.

“I don't think that I personally am doing that much, but I do think that if I have skills that are useful, that this is an opportunity to be helpful and to be here in solidarity with the Ukrainians, who are having a much worse time of it than we are.”

Returning to the battlefield

“You know, I still have this feeling that I didn’t finish something, that I could have done more,” Batiushka tells us at one point. “It really hurt when they said that’s it, you’re completely discharged from military service, no one will take you back anywhere.”

He recalls a doctor at one of the hospitals asking why he would want to return to the frontline. “I answered: ‘Do you think it’s all over, or what?’” The desire among servicemen to return to duty is something nearly every doctor notes after speaking with them.

“All of the soldiers that we see are true heroes,” Dr. Adamson says. “What is most impressive about virtually all of them is, notwithstanding their terrible injuries, the majority of them will say: ‘I want to get better as fast as I can, I want to go back to the front line, I want to be with my buddies to help out. The Ukrainian soldiers really demonstrate the best of resilience, the best of courage, the best of strength.”

Having already helped almost 200 Ukrainians, the Face the Future mission doesn’t plan to stop. The team is set to return in the spring of 2026 to perform more surgeries and reach even more Ukrainians in need.

-8321e853b95979ae8ceee7f07e47d845.png)

-0666d38c3abb51dc66be9ab82b971e20.jpg)

-73e9c0fd8873a094288a7552f3ac2ab4.jpg)

-9a7d8b44d7609033dbc5a7a75b1a734e.jpeg)

-554f0711f15a880af68b2550a739eee4.jpg)

-6ead6a9dd508115a5d69759e48e3cad1.jpg)

-29a1a43aba23f9bb779a1ac8b98d2121.jpeg)