- Category

- Perspectives

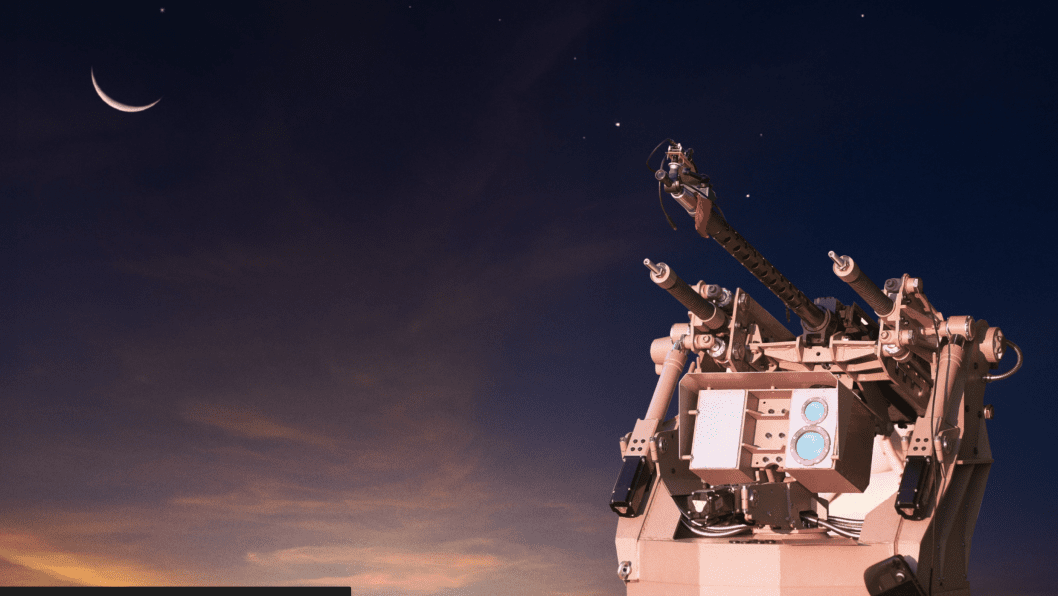

Control War Drones From Any City? Ukraine’s Top Tech Official Talks AI, EU Partnership, and the Future of Combat

How does Ukraine plan to counter Russia’s numerous Shahed drone attacks? From co-developing next-gen AI weapons with the EU to developing its own ballistic missiles, Ukraine’s Digital Transformation Minister Mykhailo Fedorov outlines how tech is reshaping Ukraine’s fight—and what’s coming next.

Ukraine and the European Commission launched a new initiative in Rome on July 11: BraveTech EU. The initiative is part of the URC25 Recovery Conference.

The program will allow European defense-tech startups backed by EU funding to test their innovations directly on Ukraine’s battlefield, mirroring how local companies have operated under Ukraine’s Brave1 platform. The most successful technologies will be fast-tracked for deployment by Ukrainian forces.

European technologies could be valuable to Ukraine on the battlefield—especially as Russia still holds an advantage in certain areas—says Ukraine’s Deputy Prime Minister and Minister of Digital Transformation, Mykhailo Fedorov. Even a one-day or one-week pause, he warns, could cost the country dearly in the race for technological superiority.

We spoke with Fedorov about how the new initiative will work, what Ukraine stands to gain, and how the country is responding to Russia’s Shahed drone threat—from interceptor tech and UAV incentives to AI-driven warfare and domestic missile development.

You and European Commissioner Andrius Kubilius announced the new initiative today in Rome (the interview was recorded on Friday, July 11—ed.). It’s about tech exchange, battlefield testing, and startup funding. How will it work, and why does Ukraine need it?

Brave1 has already become Ukraine's largest angel investor in defense tech. In total, startups under the project have received over 2.2 billion hryvnias ($53 million) in grants. This year, even more will be issued.

How it works: we set technical tasks for the market, search for solutions, and then scale them—we provide grants and test them at proving grounds and on the battlefield.

Deputy Prime Minister for Innovation, Education, Science and Technology Development. Minister of Digital Transformation of Ukraine

Brave1's successful experience is now being scaled to Europe. We're launching a European Brave, where we can continue to invest in both Ukrainian and European projects. There will be a separate budget for this.

We're creating a separate market for defense startups. For example, there are solutions involving CRPA antennas and autonomous drones. European companies have them, but there was no platform to collaborate with them. Now we can run a hackathon, grant the winner, and then test everything on the battlefield in Ukraine.

Could these be joint projects with Ukrainian companies?

They could be individual European or Ukrainian projects, or joint ones.

Will there be a tech exchange between Ukrainian companies and EU startups?

We hope the tech exchange will happen organically. It’s important to emphasize that we’ll apply everything we did for Ukraine—but now involving European startups as well. As their contribution, the European Commission is providing funding. They’ve told us: We have startups, but they’re not changing the course of the war in Ukraine. Can you help by creating a platform where grants lead to real, tangible outcomes?

Ukraine and the EU will initially each contribute €50 million (approx. $58.4 million) to the BraveTech EU fund. What kind of sums should the fund operate with in the future?

It depends on how we start using the funds and the market size. We already see countries from both the EU and beyond ready to join the program. NATO separately wants to allocate funds.

So, you saw that Europe has technologies Ukraine can use and proposed this startup-based format to the European Commission?

Technologies have always been there. But there was no mechanism to build trust with these startups, to bring them to Ukraine, or to give them feedback that something needs improvement. When you give them money, you can also give feedback and test more, so you become partners. Our hypothesis is that by creating a unified market for defense startups, we can deepen cooperation with European companies. Maybe we'll see Ukrainian startups merge with European ones, as already happens in Ukraine.

Will existing drone manufacturers be involved in the initiative? And if so, how?

If they launch new projects and need resources—why not? Usually, projects come in where there's already an MVP and they want to scale it. Or the startup has an idea and wants to build a prototype. Companies with large contracts may have up to a 25% margin, as allowed by the government. So they can reinvest those funds.

What exactly could Ukrainian defense-tech startups produce in collaboration with European companies? What should be the priority—drones, electronic warfare, explosives, or something else?

A strategic committee will decide on the priorities. These will be projects creating highly autonomous products, anti-guided aerial bombs, and anti-drone projects, such as those using fiber optics. Then we can scale all this depending on battlefield needs. What the battlefield will look like in six months—we don't know.

Just recently, there was a story about American troops at a training ground in Germany learning to drop grenades from drones—something that already feels like ancient history to Ukrainian soldiers. You’re in regular contact with Western counterparts. Would it be fair to say that Ukraine is now ahead of many NATO countries in military tech, at least in some areas?

We have different war doctrines. In the US, it's more of an air defense doctrine, where they aim to gain superiority in the sky, and for that, they need aircraft—manned and unmanned. They take out radars, then launch missiles. Ukraine’s battlefield looks different. We have a 1,200 km front line, and no one can gain air superiority. We're already fighting with other technologies, other types of drones. In this area, we are global leaders.

But if we're talking about planes and similar advanced tech, then of course, we're not leaders there. NATO is learning from us how to adapt its doctrines to modern warfare, and we are looking for strong solutions from our partners, adapting them to our realities and giving feedback.

In short, in some categories, we have complete superiority, and in others, we need a few or even dozens of years of R&D. The future definitely belongs to unmanned aircraft. Creating a plane, then an unmanned version of it, requires huge investments and years of research. The same goes for fully autonomous drones. Right now, our partners have begun learning rapidly - they're investing in Ukrainian companies, opening Ukrainian companies in their own countries. Something has shifted in the West over the past year - there's been a fundamental change, and now they're engaging with our companies and growing at incredible speed.

Will Ukraine be opening up exports?

Ukraine’s President Volodymyr Zelenskyy has already announced that exports will be restricted. I can't say how exactly this will work, because I'm not handling that matter.

What about interceptor drones? Both you and President Zelenskyy have said a solution exists. But can it handle the scale—700 to 1,000 drones that Russia may launch almost daily? Do we have a technological answer to that threat?

Yes, interceptor drones are currently the most effective response. I can only say what the President has already said—the solution has been found, it's being scaled, and more than one company is working on it. We understand clearly what needs to be done next.

What about Russia's jet-powered drones? Can Ukraine’s interceptors handle them?

Companies that have reached certain solutions are already working on countering jet drones, figuring out how to operate in cloudy weather, etc.

It's a constant race. Russia launches Shahed UAVs, Ukraine counters with new electronic warfare systems. Then Russia adapts—adding 12 to 16 antennas to bypass our defenses. Ukraine respond again, and they escalate with jet-powered drones. The cycle feels endless.

That's exactly how it is. If we stop even for a day or a week, we risk falling behind Russia for good. That's why many companies are doing R&D, looking at what's coming in a week, in two weeks, in six months. Everything changes in real time.

Is Ukraine keeping up with those changes?

In some areas, yes, in others—not yet.

Take fiber optics, for example. Soldiers say Russia has the upper hand. Where does Ukraine fall short—is it a lack of funding to scale solutions, or a technological gap?

Hard to say, because there are many dependencies. Sometimes we’re focused on other problems. Right now, for example, it's about countering Shahed drones. Russia doesn't have that problem; they have plenty of missiles and air defense systems. On a tactical level, we've always been strong, so the Russians are trying to hack our tactical advantage. They were the first to reach a solution for fiber-optic drones, and they've achieved more scale there.

We have a clear focus. You can't have success and breakthroughs in all technologies at once. This past year, we focused on interceptors for Shahed drones, and we got results. Now, maybe we'll shift focus to the tactical level and find game-changers there. We have a few more projects where we need to do our homework, in particular, fiber optics and guided aerial bombs. Until we find a way to counter those, certain frontline areas may take heavy hits.

Should Ukraine create its own Shahed analog? What would be needed to scale deep-strike drone production to the level Russia has?

We’re not publicly disclosing how many drones we’re launching or producing. The issue isn’t that our drones are significantly worse than the Shahed UAVs. The problem is that Russia has more air defense assets—they can intercept our drones using aircraft and helicopters. Our air defenses don’t reach their helicopters, but theirs can reach ours. They also have a large stockpile of air defense missiles, which allows them to shoot down our Shahed analogs. In that sense, yes, we feel the difference. But when it comes to the quantity, quality, and flight capabilities of our drones—well, for obvious reasons, we’re not sharing that information.

What’s the status of Ukraine’s ballistic missile programs? Are you personally involved?

We've issued several dozen grants through Brave1 for ballistic and cruise missiles. The companies that received the grants are now testing their products, and we'll evaluate them based on the results.

FPV drones have become the de facto main weapon of the war and have already changed its course. But is this the peak of their evolution—or will we see a new wave of innovation, perhaps driven by AI?

We understand all the next evolutionary and revolutionary stages of military tech. FPV drones and autonomous copters will evolve. First, they'll better identify and strike targets even under electronic warfare. Then, they'll reach certain points without a connection. Eventually, drones will operate as a swarm in a shared network.

Drone autonomy will grow, but this requires funding for R&D. You can't just assemble a product from various components anymore—you need to invest in R&D and engineers. All this needs proper infrastructure, people, and scientific staff.

Is Ukraine discussing with European partners how to reduce dependence on Chinese components?

If we give Ukrainian companies proper profit margins, they will begin to scale and localize component production. We already have one drone made entirely from Ukrainian components, and I know of many projects with 50–80% localization. Higher margins enable companies to reinvest, which helps reduce dependency on Chinese supplies.

The share of American and European components is growing. The integration we’re working on could prompt European companies to start producing more radars, cameras, and other critical tech. We want European companies to "feel" the battlefield with their fingertips—then they'll better understand the market and what needs to be made. Maybe that will also influence component localization.

At this stage, how is AI impacting combat operations, and how do you see its role evolving in the coming months? Who currently has the edge—Ukraine or Russia? And to what extent can AI physically protect troops by reducing the need for operators near the front line?

AI is already actively used to decode imagery, target enemies, interpret real-time transmissions, and even for AI-guided adjustments on FPV drones. We're launching a dedicated grant program in this area—this is the future of the battlefield. We need to get UAV operators off the battlefield.

Russia has created a Rubicon military unit that actively hunts our drone operators. Our mission is to enable remote operation as much as possible and eventually implement autonomy. That's the next stage of warfare. The goal is for an operator to control a battlefield drone from any city in the country. Beyond that, full drone autonomy. But that's probably a matter of years.

Recently, you announced changes to how target kill verification works under Brave1, along with updates to the e-point system. If I understand correctly, units no longer receive direct funds to purchase drones—instead, they now select weapons and equipment directly from a kind of marketplace?

That’s right. It's already essentially the Brave1 marketplace. We've expanded the categories—you can choose electronic warfare systems or other types of gear. A unit has a point balance, they make selections, the state pays the companies directly, and delivery and logistics follow. No need for contracting under the bonus system.

How would you assess the effectiveness of the e-point system?

The numbers speak for themselves—some units have grown significantly and started receiving more drones, precisely thanks to this incentive system. There are also many indirect results. On one hand, a unit grows; on the other, we get data that helps us make sound management decisions.

Thanks to this, we understand the depth of impact on the enemy: where we hit infantry, where we hit vehicles, how to extend strike distances, how many targets we find per day or week, and how many we hit—so, the conversion rate. We know how many tools we lack, where we’re shooting down enemy recon planes, how many, and in which sectors we’re not succeeding—and why, such as whether there’s radar coverage. We’ve gathered real-time battlefield data that no other system has.

Has target verification proven to be a challenge across different units?

A verification culture has already taken root. There are very responsible units—they upload high-quality data. We have several dozen verifiers who check this. Plus, we share one unit's data with others—there's always a way to verify.

What are your current plans for Brave1? Are there any new initiatives you can share?

We’ll be testing more products directly on the battlefield. President Zelenskyy has signed a decree assigning 300 soldiers to work with Brave1. Thanks to this, we’ll be able to identify more potential battlefield game-changers. Brave1 is also receiving increased funding, which will allow us to launch more grant programs. I expect that over the next six months, Brave1 will make significant progress toward its mission—finding tech solutions that can shift the battlefield dynamic.

Interview by Rostyslav Shapravskyi, Editor-in-Chief of RBC-Ukraine.

-588ae190d45987800620301cc34e2cf8.png)

-886b3bf9b784dd9e80ce2881d3289ad8.png)

-c42261175cd1ec4a358bec039722d44f.jpg)

-46f6afa2f66d31ff3df8ea1a8f5524ec.jpg)