- Category

- War in Ukraine

He Came to Russia from Africa to Study Civil Engineering. They Put Him in a Military Truck

“I will say everything as it happened without leaving anything out, unless it's something I have forgotten,” a young African man says while sitting in a room in an undisclosed Ukrainian city. He is a soldier in the Russian army, captured by Ukrainian forces. The POW describes everything that happened to him, from the moment he decided to study in Russia.

This article is based on an interview with a prisoner of war. While some inconsistencies in dates and details were noted, we were unable to verify the account through other sources. The interview was conducted in Kirundi, one of Burundi’s official languages, and translated into English.

From Burundi to Russia

It all started when Jean Bosco Akimana decided to go to Russia “to improve his knowledge and skills.” Coming from a family of four children, the 32-year-old Burundian explains that in African countries, after studying abroad, “you come back to your African country with respect. You can earn more money.”

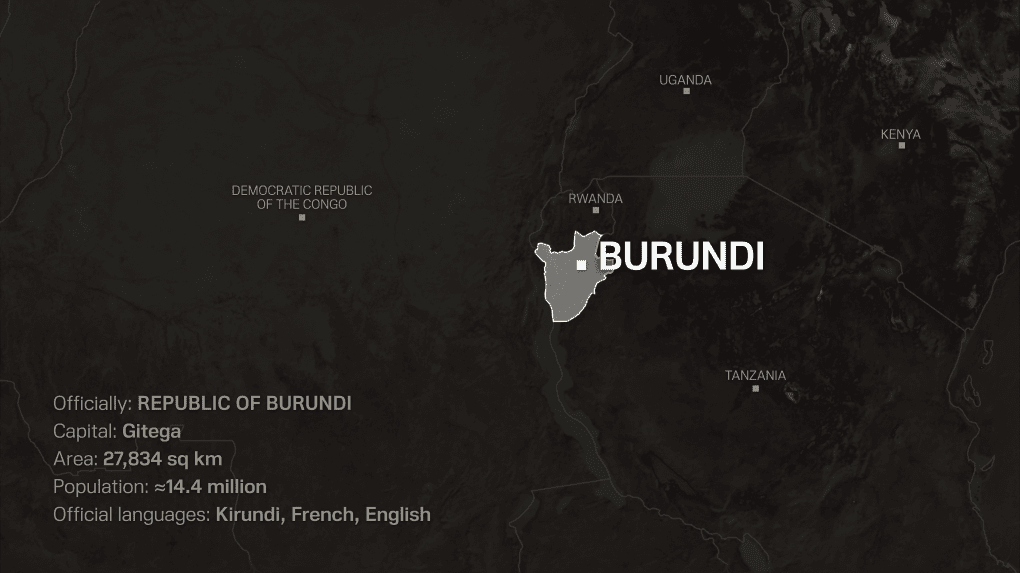

Burundi, situated between Rwanda, Tanzania, and the Democratic Republic of the Congo, is one of the poorest countries in the world. According to the World Bank, more than seven out of ten of its residents live below the poverty line.

After finishing school, Jean Bosco Akimana didn’t go to university. Instead, he started his own business, a shop where he sold a variety of beverages—from water and soda to alcohol. “I earned between $300-400 per month. That money supported me and I lived well,” he says, adding that it was a sufficient salary for a young person.

Everything changed after Akimana came into contact with a man named Elias, who told him about the opportunity to study in Russia. Akimana asked Elias to be one of those candidates. “He told me to send him my passport so he could send it to Russia. He received the documents, and a month later, or a little more, I received the invitation [from the Russian embassy in Burundi—ed.].”

Akimana says that he didn’t know much about the country in which he was planning to study. “We learned that Russia is a big country. I also knew that students from our country had gone to study in Russia before.” However, he was aware of Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine. “I’d heard about the war between Russia and Ukraine, but I didn’t know that a student could be sent to war; I thought that only trained soldiers went to war.”

We bring you stories from the ground. Your support keeps our team in the field.

After receiving the invitation, a man went to the Russian embassy to start the visa application process. Elias had initially told Akimana that he wouldn’t have to pay for anything. Nevertheless, as soon as his visa was ready, it turned out the Burundian had to pay his own tickets to Moscow—$2,000, “and the money that I had paid would be refunded after four days in Russia.”

That refund never came.

Elias also promised that after a few months of studying in Russia, students would be paid. When asked if that hadn't seemed suspicious, Akimana explains: “"I thought that maybe after we finished our studies, organizations would offer us jobs.” Indeed, the Russians found him a job less than a week after arriving in the country.

A training ground instead of classrooms

“After I got the visa, Elias told me to get ready, and that we would go to Russia together with others,” Akimana recalls. He says that his plans in Russia were to study Civil Engineering at the Faculty of Construction. “There were four of us who went to Moscow, all Burundians.” They had already met before, when applying for their visa at the Russian embassy in Bujumbura. “They also told me they had invitations to study in Russia.”

At the airport in the Russian capital, a person was waiting for them—Alexandra. “I think she worked with Elias. She took us to another city—Orel,” he continues. After arriving in the city on November 11, 2025, the Burundians had one day of rest. Then, Alexandra returned, took the men to be photographed, and then bought them phones and SIM cards. The very next day, “an elderly man came,” to pick the men up. Together they went to an office where they received bank cards and signed some documents. According to Akimana, none of them knew what was written on those papers.

After we signed, we went outside and found a military car waiting for us.

Jean Bosco Akimana

POW from Burundi

Akimana says they didn't know what to do in that situation. “We were not aware of what we signed for. We thought we were signing to go to school, but surprisingly, we were taken away by soldiers.” The car took them away. “We traveled for a long time. We were scared, but we finally arrived at a camp.”

As soon as men arrived, they were provided with military uniforms. The next day, the soldiers told them they would start training. “I refused to go, and they told me to stay there. Those who were with me, the three guys, were afraid. They just went where they were told to go,” Akimana says. “I looked for anyone I could explain my problem to, but I didn’t find anyone. There was nobody who could understand my language. I saw a Pakistani guy and asked him, ‘What could be written on these papers I signed? Explain to me.”

According to the Burundian, the Pakistani man told him that the papers he signed were a military contract for being a soldier, and he wasn’t going to study. “He told me that I had to accept this because I had already arrived at the camp. I told him I couldn't go into the military while my family thought I was studying. I stayed there for some days, trying to find a way to return to my studies, but they refused.”

In another conversation, the soldier from Pakistan told Akimana that Russia pays 2.2 million rubles ($27,300) for signing a contract. “I later asked him: Why didn't I get any money? I didn’t get any rubles. Not even one. What is going on?” Though he does recall seeing a message on his phone that 4,800 rubles (almost $60) were in his bank account.

“Later, a commander appeared and said that everyone had to buy a radio device,” Akimana continues. “I went and told him that it was possible to buy it, but I needed to send money to Burundi first. He gave me back my phone, and when I checked my account, there were only 2,000 rubles ($25).” After showing this discrepancy to the commander, Akimana was told the Russians had forwarded the data to the police, so they could find out who had allegedly been using his account. Meanwhile, the commander decided the Burundian would start training like everyone else.

“I trained for two weeks and a few days, but the others did it for four weeks,” he says. “For those days I didn’t train, it’s because I was looking for ways to get back. We learned to shoot and to throw grenades. They taught us how to move inside the trenches. They taught us how to set mines, but we, Africans, were not allowed to practice. They taught us how to treat someone in case of injuries, using the tools they had given us.”

Akimana says that he and the rest of the newcomers lived in difficult conditions and were treated badly. “We were hungry; they fed us badly; and sometimes they were not giving us food, until they took us to the frontline.”

After completing their training, the soldiers were sent to the front. “They took us to a place they had shown us on the map—Donetsk.”

With drones overhead

Akimana says that before being captured by Ukrainian soldiers, he had spent “like 10 or more days” in the Donetsk region. He insists that he hadn’t completed any missions, except for repairing some equipment. “Personally, I didn't want to attack. I wanted to escape.”

After arriving in the Donetsk region, a group of soldiers, including Akimana, was taken to an unknown place. Later, Russians brought motorcycles and took them—two Burundians and two Russians—to the positions. There was a commander who sent them to another place. “He showed us a post and said, ‘You two go there.’ And then we went, and it wasn’t easy, because there were drones overhead and there were bombs constantly hitting. But they ordered us to go until we reached where they had shown us.”

Finally, they arrived at the location that had been shown to them and found another soldier who guided them to their next destination. “The place we went to was very difficult to reach,” he says. “A Russian soldier went on ahead and got injured by a mine.”

Akimana says there were two of them in their position, and this place was close to where the Ukrainians were. “We were there for about a week or more,” he says. “When we arrived, we didn’t have any food. We didn’t even have water. I told my companion, who was a Russian citizen, that: ‘I’m leaving.’ He thought that I was going back to the Russian troops.”

However, the Burundian decided to hand himself over to the Ukrainian soldiers.

“Russia is not a peaceful place”

“When I approached the Ukrainian soldiers, I didn’t have any weapons or anything to fight with,” he says. “The Ukrainian army captured me, and they treated me well. I was thirsty, and they gave me some water.”

Akimana’s passport and phone were confiscated, and he was secured and taken to another location. “They said my phone would be returned. They handed me over to two Ukrainian soldiers, and they took me to another position.”

Now, while in custody, Akimana is trying to convince the African people to avoid traveling to Russia.

I have a strong message for the young men and any adults. Russia is not a place to go. I’ve seen it with my own eyes. I went there, and I saw what they do.

Jean Bosco Akimana

POW from Burundi

“There are numerous advertisements encouraging citizens to continue their studies or work in Russia,” says Akimana. “Just be careful. You might find yourself at war.”

“Russia is not a peaceful place. It's a place for war,” he concludes. “I just want to add that I have a request from Ukraine and from Human Rights organizations. This is not a demand, but help me return to Burundi if possible.”

-f223fd1ef983f71b86a8d8f52216a8b2.jpg)

-73e9c0fd8873a094288a7552f3ac2ab4.jpg)

-605be766de04ba3d21b67fb76a76786a.jpg)

-0c8b60607d90d50391d4ca580d823e18.png)

-29a1a43aba23f9bb779a1ac8b98d2121.jpeg)

-76b16b6d272a6f7d3b727a383b070de7.jpg)