- Category

- War in Ukraine

Why Russia’s Drone Swarms Are Getting Deadlier by Flying Higher

Russian drone swarms are still loud, slow, and easy to spot on radar. But now they’re harder to stop, flying just high enough to force Ukraine to trade gold for garbage, one interceptor at a time.

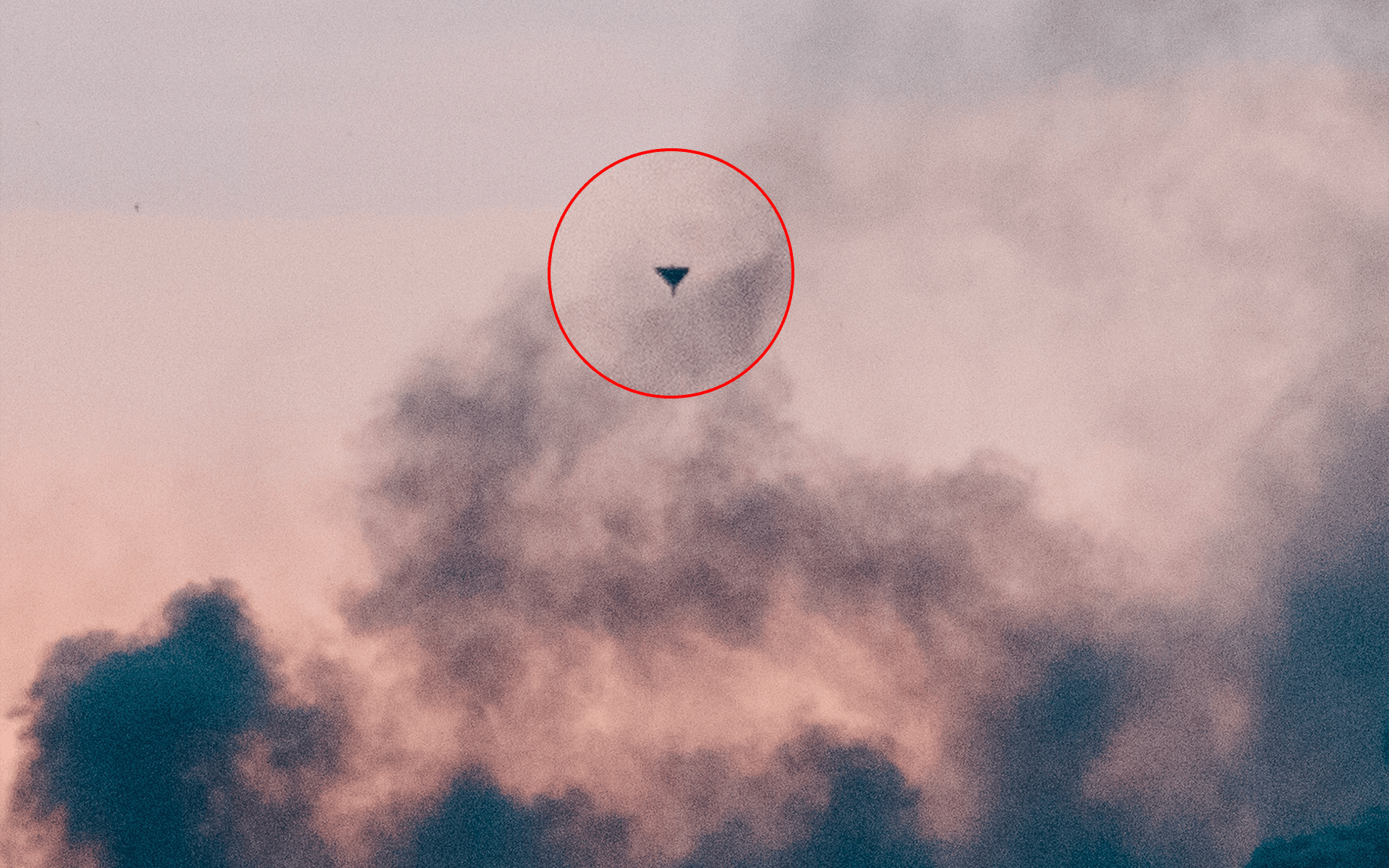

Shahed drones—based on Iranian designs but now mass-produced in Russia—aren’t stealthy or high-tech. But when 400 of them swarm in a single night, flying erratic patterns at altitudes unreachable by small arms before suddenly diving toward their targets, the goal is clear: overwhelm Ukrainian air defenses and wear down civilian resilience.

They don’t need precision. They don’t even need to be accurate. On a daily basis, Russia floods Ukraine’s sky with sheer volume and chaos. Ukraine can see all the drones on radar, but stopping them means using up dwindling missile reserves on cheap drones.

Western intelligence estimates that Moscow can now produce up to 2,700 Shaheds per month, along with 2,500 decoy drones designed to confuse and deplete Ukraine’s already strained air defense systems. Most fly 2 to 5 kilometers above ground—visible on radar but too high for simple weapons. Intercepting them means burning through expensive missiles night after night.

The economics of air defense

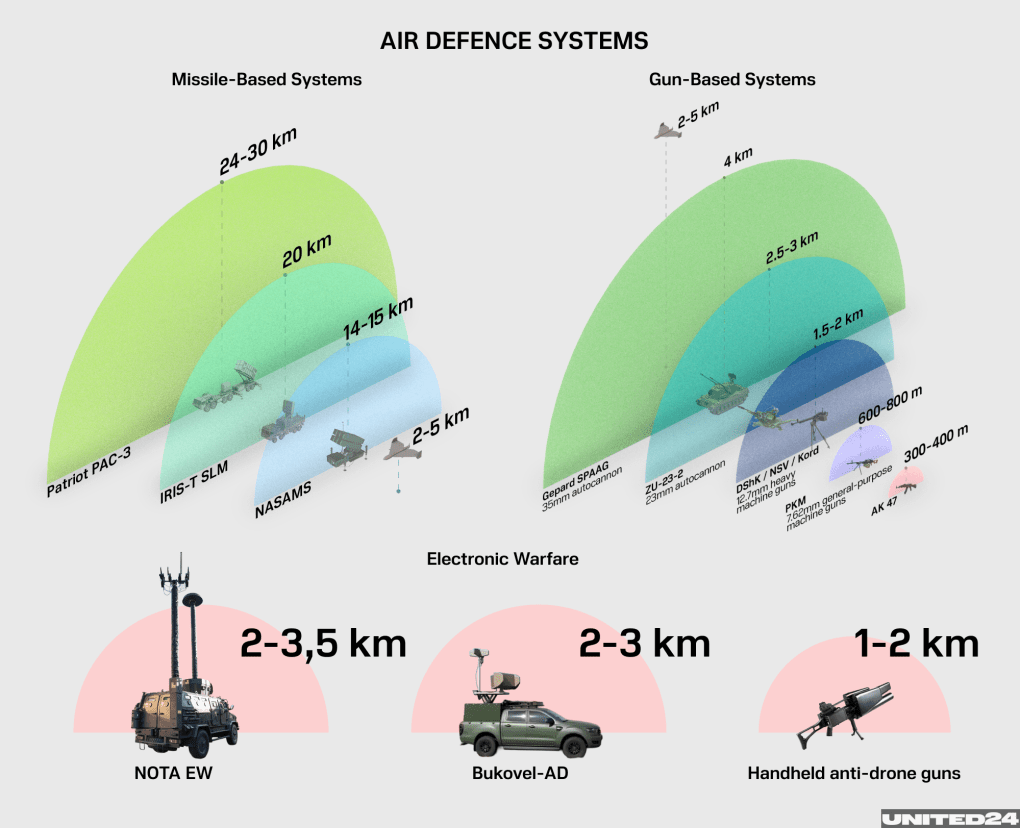

The math behind Russia’s drone war is not in Ukraine’s favor. The cost of a Shahed varies based on when it was acquired and whether it’s measured by purchase or replacement value, but if taking the cheapest possible, estimates suggest that a single Shahed drone can cost Russia roughly $20,000 to $50,000 to produce. Ukraine, on the other hand, often has to use missiles that cost ten to a hundred times more to shoot them down. A single Patriot interceptor runs around $4 million. IRIS-T missiles cost around $1,000,000 apiece, with the NASAMS interceptors falling in the same range.

Then there's the problem with altitude. Shaheds are now flying at 2 to 5 kilometers, high enough to evade small arms and many mobile anti-aircraft guns. To hit drones at that height, Ukraine has to rely on high-performance surface-to-air missile systems that were originally designed to counter aircraft or ballistic missiles, not $20,000 flying bombs.

Ukraine does have cheaper options. One is the Gepard self-propelled anti-aircraft turret, which uses 35mm autocannons. Each round costs about $1,000. It’s cost-effective, but its range is limited to up to 4 kilometers in altitude, barely within reach of the higher-flying Shaheds, and only when detected early enough. There are also laser-based systems currently being tested, such as the Ukrainian Tryzub direct energy weapon system.

Electronic warfare (EW) is another tool in Ukraine’s arsenal. Systems like Nota, Bukovel, and Anti-Drone Guns are used to jam the drone’s navigation signals, often forcing it to crash or veer off course. Unlike missiles, EW is reusable and cost-effective. But it has limitations. Jammers work best at short-to-medium range, and Russia has started hardening some drones against GPS interference or programming them with pre-loaded coordinates. When swarms of drones are launched simultaneously from multiple angles, EW alone can’t cover every approach.

Ukraine’s defense is a layered patchwork: missiles, guns, EW, and human observers. But the most reliable options are often the most expensive, and every time a Shahed gets through, the highest cost isn’t just in dollars, but in lives.

20,000 missiles that never came

President Volodymyr Zelenskyy recently revealed that the United States had once pledged 20,000 low-cost interceptor missiles to Ukraine—systems designed specifically to stop Shahed drones. But the missiles never arrived. Instead, they were quietly diverted to the Middle East, amid rising tensions between Israel and Iran.

“There is no such information [on how long that war might last],” Zelenskyy said when asked whether Ukraine’s intelligence had updated assessments on an Israeli operation against Iran. “I was constantly afraid that we could become a bargaining chip… just one of the factors in the negotiations between the United States of America and the Russians. So, next to the situation with Iran, there was also the situation with Ukraine. They are really dependent on each other.”

“For example, we had 20,000 missiles from the United States,” he continued. “We can call them ‘interceptors.’ These were inexpensive missiles, specifically for Shahed drones. When you see 300–400 drones per day against us, most will be shot down, but a certain percentage will reach the target. We were counting on these missiles. You can calculate how many we would have. We shoot down by other means as well, but 20,000 is a serious number, to be honest. The US transferred these missiles to others because of the situation in the Middle East. And for us, it was a blow.”

If 300-400 drones are launched in a single night, every night, then those 20,000 interceptors could have helped protect Ukraine for nearly two months. Two months of fewer explosions in Kharkiv, Odesa, Kyiv. Two months of safer nights. Instead, Ukraine is left burning million-dollar systems—Patriots, NASAMS, IRIS-Ts—on low-cost suicide drones just to keep the sky from falling.

Another massive attack on Kyiv

Kyiv has been under fire before. The capital’s air defenses are among the most advanced in Europe. But nothing is invincible—not when Russia launches 440 drones and 32 missiles in a single night. On June 17, one of the deadliest strikes of the year hit the city, killing 24 people—including 62-year-old American volunteer Grendy Frederick Glenn—and injuring 134 more.

Glenn, a US citizen who had come to Ukraine to help train combat medics, died in his sleep. The US Embassy condemned the attack, calling it a senseless strike and a reminder of why continued support for Ukraine still matters.

The worst damage came in the Solomianskyi district, where a ballistic missile collapsed an entire section of a nine-story apartment building. It took more than 39 hours and over 400 emergency workers to dig through the wreckage.

“We were literally one building section away from dying,” said one man, waiting in line at a rescue tent. Another survivor recalled hearing “a very loud, intense whistling sound… That’s when I knew—that was it.”

This wasn’t a military site. It was an apartment block full of people trying to sleep through the night. One missile got through, and that was enough. Air defense is life support for the Ukrainian wartime cities. And when it fails, the cost isn’t just metal and rubble. It’s names, faces, and the people who won’t wake up tomorrow.

Russia’s drone empire expands

Russia’s drone war is no longer just a battlefield tactic—it’s a transnational production pipeline, with Iran supplying the designs, Russia mass-producing at scale, and now North Korea stepping in to learn and replicate the model.

Japanese and Ukrainian intelligence reports that North Korea is preparing to send up to 25,000 workers to Russia’s Yelabuga facility, a key drone manufacturing site in Tatarstan, to assist and train in Shahed production. The goal is twofold: boost Russia’s output and transfer know-how to North Korean facilities, where Pyongyang is preparing to build its own fleet of long-range attack drones based on Iran’s “Geran” and “Harpy” platforms.

Ukrainian intelligence chief Kyrylo Budanov warned that some of these drones could be sent back to Russia for use against Ukraine, while others could dramatically shift the military balance on the Korean Peninsula. Russia, in return, is providing North Korea with mobile air defense systems, electronic warfare equipment, and support for a major military-industrial expansion.

Meanwhile, Ukraine and Israel have begun striking at the source. In mid-June, Ukraine hit the Yelabuga plant with a glider bomb, while Israel targeted Iran’s Isfahan drone factory as part of Operation Rising Lion. These facilities produce thousands of drones monthly, many of them destined for strikes on Ukrainian cities.

But strikes alone aren’t enough. Intelligence, sanctions, export controls, and legal action are all needed to dismantle the Russia–Iran–North Korea drone triangle before it becomes an even more permanent axis of warfare.

-554f0711f15a880af68b2550a739eee4.jpg)

-206008aed5f329e86c52788e3e423f23.jpg)

-1afe8933c743567b9dae4cc5225a73cb.png)

-46f6afa2f66d31ff3df8ea1a8f5524ec.jpg)