- Category

- War in Ukraine

Why Would Russia Revive Horse Cavalry on the Battlefield in the Age of War Drones?

In a war defined by drones, satellites, and electronic warfare, videos of Russian soldiers on horseback in occupied Ukraine are a symptom of exhaustion—an army running out of fuel but rich in imperial myths.

In 2025, for the first time since the 1940s, Russian mounted cavalry appeared on the battlefield—only to be destroyed by a Ukrainian drone.

Before this first documented casualty, months earlier, observers noticed that some Russian frontline units were using donkeys and horses to carry ammunition and equipment through muddy terrain. The internet reacted instantly. Memes and articles mocked what seemed like a regression to medieval logistics.

Yet Russia persisted. An independent Polish military news outlet Defence Blog published a video on October 4, recorded by a Ukrainian FPV drone: the camera captures a Russian soldier trying to hide behind his horse before the drone explodes.

A Ukrainian operator from the 132nd Battalion strikes a Russian cavalryman who clings to his horse in fear.https://t.co/TnUu97xLRA pic.twitter.com/xSigfttOFF

— Yigal Levin (@YigalLevin) October 4, 2025

The contrast is startling—nineteenth-century cavalry tactics colliding with twenty-first-century drone warfare. Why would Russia, a nuclear power boasting hypersonic missiles, rely on animals on the battlefield?

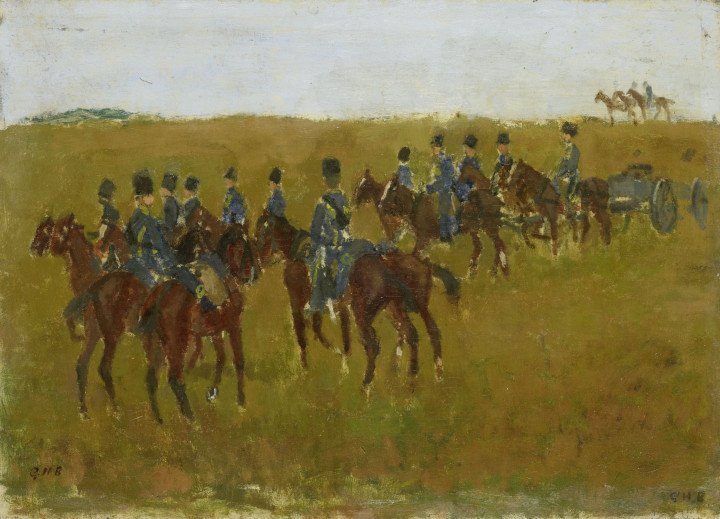

The theory of cavalry—speed, shock, and flexibility… in the 19th century

Before the age of engines, horses were the embodiment of speed, shock, and flexibility. In On War (1832), Prussian strategist Carl von Clausewitz described cavalry as “the arm for movement and great decisions”—a force that could turn uncertainty into momentum before the enemy reacted.

Mounted soldiers carried both physical and psychological weight. Cavalry provided reconnaissance, communication, and pursuit capabilities that foot soldiers could not match.

But Clausewitz also warned of the limits of the horse in prolonged or constrained conflicts. He wrote that cavalry was “important only if the war extends over a great space,” a condition far removed from the trench-style warfare that defines large parts of the current front in Ukraine.

Clausewitz also noted the enormous logistical burden of equine warfare: “The weight of the forage required is three, four, or five times as much as that of the soldier’s rations required for the same period of time.” In practical terms, a horse consumes far more than it carries—turning every mounted unit into a logistical liability in long campaigns. For an army already struggling with fuel and supply shortages, relying on horses underscores the depth of Russia’s logistical problems.

Horses require more care than soldiers and are highly dependent on terrain and weather. Their effectiveness depends on breeding and stamina; otherwise, they become a burden rather than an advantage. In today’s war, where Russia treats manpower as expendable, investing in well-trained horses and the cavalry skills needed to mount them appears far from a priority.

Ultimately, industrial warfare ended that age. Machine guns and artillery made open-field charges suicidal. By World War II, horses survived only in reconnaissance or supply roles. The Soviet army kept horse units until the early 1950s, mainly for terrain where vehicles failed—swamps, forests, and frozen rivers.

A brief history of Russia’s love affair with horses

Horses are deeply woven into the mythology Russia claims as its own—rooted in its reimagining of Cossack history.

But the Cossacks originated primarily in what is now Ukraine, not Russia. The earliest Cossack communities appeared in the Dnipro River basin, in today’s Ukraine Zaporizhzhia region, in the 15th–16th centuries, as self-governing groups of runaway peasants, adventurers, and frontier warriors.

The Zaporizhian Cossacks embodied a distinct Ukrainian political tradition that was later absorbed and rewritten by Russian imperial ideology, explained American historian Timothy Snyder in an article about the complexity of Ukraine’s national history, simplified and absorbed by Russian official historiography.

Over time, Moscow co-opted some Cossack hosts, especially those further east like the Don Cossacks, turning them into loyal instruments of imperial expansion.

During the civil war, the Red Army relied heavily on cavalry—led by commanders like Semyon Budyonny—when roads and trucks were scarce. Early Soviet propaganda cast these horsemen as the embodiment of revolutionary vigor: the proletariat in the saddle.

Even as tanks and aircraft took over the battlefield, horses remained vital. In World War II, the Soviet Union deployed millions of them to haul artillery and supplies through the mud of the Eastern Front. Many died alongside their riders in the many battles of the war.

After 1945, the horse became a relic and a symbol—no longer practical, but politically powerful. Soviet posters and parades celebrated cavalry as proof of courage, tradition, and unity.

In 1955, the last Red Army cavalry division—the 5th Guards Don Cossack Cavalry Division—was reorganized into a mechanized unit.

But this so-called love affair should not obscure Russia’s disregard for animals, evident in the atrocities it deliberately commits against them in Ukraine. On July 11, 2025, a drone strike on a stable in the Odesa region killed several horses. On October 3, a pig farm was targeted in the Kharkiv region, leaving about 13,000 pigs dead.

The owner of the Odesa horse stables that were targeted by Russian drones yesterday, with a final farewell to Camellia, the stable's favorite.

— SPRAVDI — Stratcom Centre (@StratcomCentre) July 12, 2025

Several other horses were injured and stables destroyed when Russians targeted them with a shahed drone. pic.twitter.com/XLE9R7ZnCC

⚡️ Russia keeps targeting farms in Ukraine.

— UNITED24 Media (@United24media) October 3, 2025

A Russian drone strike on a Kharkiv region killed 13,000 pigs and destroyed 8 of 10 barns after deliberate hits on livestock shelters. pic.twitter.com/RcdsbABuVJ

Horses on the drone battlefield

The first signs of Russia using pack animals appeared in winter 2025 — around the same time it began diversifying its assault “vehicle fleet” with motocross, golf buggies, and even electric scooters.

❗️The 🇷🇺Russian military has increasingly begun to use electric scooters at the front pic.twitter.com/UHkmzELXxZ

— 🪖MilitaryNewsUA🇺🇦 (@front_ukrainian) August 10, 2025

In August, further evidence once again showed Russia’s use of horse cavalry. The commander of a “Storm” special forces unit said his troops are now being trained to ride horses, Kommersant, a Russian outlet close to the Kremlin, reported. The training relies on the idea that horses’ “instincts” help them avoid landmines and move better at night or in rough terrain, he said.

But the promotion of a horse unit may serve internal propaganda as much as tactics—masking fuel shortages, lack of assault vehicles, poorly trained and exhausted soldiers. In a war dominated by drones, concealing thermal signatures is essential—something a massive living, unarmored animal cannot do.

What is said about this “return”

A notorious pro-Russian military blogger WarGonzo welcomed the return of horses to the battlefield. “I am sure we will soon witness the historic return of the Russian cavalry to the ranks,” he said, “Let’s wish Khan and his modern ‘horde’ luck—with the expectation of some epic footage from the front.”

Military analyst Phillips O’Brien, a professor of strategic studies at the University of St. Andrews in Scotland, told the The Wall Street Journal : “I’m not sure the resuscitation of old technology—nets, shotguns, horses—is out of choice. They are desperate attempts to cope with unmanned aerial vehicles.”

It’s worth noting, however, that after a wave of online mockery over Russian motorcycle assaults, Ukrainian troops have also adopted two-wheel vehicles, which have proved useful in certain conditions. Will the same happen with horses?

Interviewed by The Wall Street Journal, Ukrainian Army Sgt. Ihor Vizirenko lets open the question. “But then bikes being used in assault took us by surprise, so who knows?” he said. “A horse would run faster than a man in a field.”

A regime stuck in its own myths

Beyond possible—and likely desperate—tactical gains on the battlefield, this move seems to be rooted in Moscow’s use of symbols. The Kremlin has systematically reworked historical narratives to justify its war against Ukraine—rewriting textbooks, funding glossy “history parks,” and punishing dissenting versions of the past. Victory Day pageantry, meanwhile, elevates an image of an invincible state moving from one triumph to the next.

Russian leader Vladimir Putin has himself posed shirtless on horseback in a Siberian landscape—part of a region first occupied by Siberian Cossacks and only fully integrated into the Russian Empire in the 19th century, with some of its outermost areas as late as the 20th century.

As Russian rights advocate Oleg Orlov, interviewed by AP, put it, “history has become a hammer—or even an axe.” The same aesthetic—Cossack riders, Red Army horsemen—helps explain today’s propaganda value in showing horses at the front, even when drones render cavalry obsolete.

Moreover, Russia’s reliance on outdated tactics contrasts with its simultaneous aerial provocations. In recent months, NATO countries have intercepted multiple Russian jets and drones near Polish and Baltic airspace, underscoring how Moscow’s war now stretches from the trenches of Ukraine to Europe’s skies.

In the end, technology devours nostalgia. Cavalry no longer inspires fear. Drones do.

-f223fd1ef983f71b86a8d8f52216a8b2.jpg)

-24deccd511006ba79cfc4d798c6c2ef5.jpeg)

-554f0711f15a880af68b2550a739eee4.jpg)

-f88628fa403b11af0b72ec7b062ce954.jpeg)

-605be766de04ba3d21b67fb76a76786a.jpg)

-0c8b60607d90d50391d4ca580d823e18.png)