- Category

- World

How Ready is Europe for War Against Russia?

Europe plans to spend €800 billion rearming by 2030. Russia has also tripled its weapons production since 2022 and is building up reserves. Five defense experts assessed whether Europe can close the gap in a timely manner.

Russian officials are laying the groundwork to exit international arms control agreements, the US-based think tank Institute for the Study of War (ISW) reported earlier in June, citing this as a part of preparations for a potential military confrontation with NATO.

After years of attempts to restore relations with the Kremlin, European countries pledged to increase their NATO defense spending to 5% while the EU unveiled the ReArm Europe plan, an ambitious initiative estimated at €800 billion ($842 billion)

But is this enough to counter Russia’s ever-growing war machine that’s threatening the safety of 744 million Europeans?

To answer the question, we examined three major parameters that help assess the country’s readiness for war: defense spending, weapons production rate, and the size of its armed forces, consulting five leading European defense experts.

The budget game

Russia’s military budget has been growing over the years, even by hurting its own National Wealth Fund.

In 2025, the Kremlin increased its defense spending from 10.4 trillion rubles ($133 billion) to 13.5 trillion rubles ($126 billion), which accounts for roughly 32.5% of its budget. In 2026, Russian budget spending on the army and law enforcement agencies should amount to 16.84 trillion rubles ($217.2 billion).

“Russian budget numbers are not real. The true amount is both much higher, and their costs are far lower,” says William Alberque, Former Director of Strategy, Technology and Arms Control, when assessing Russia’s military expenditures. French Air and Space Power expert Adrien Gormans concurs with Alberque, adding that “Western tanks cost $8-10 million compared to Russian tanks at $1.5 million from the factors.”

The EU’s military spending appears to be indeed tighter. In 2025, the Union allocated €1.8 billion ($2 billion) to address defense challenges.

Since NATO would defend Europe in case of a Russian offensive against one of the alliance's member states, the NATO budget should also be taken into account. While the US contributions accounted for about 16% of NATO’s common funds, the European and Canadian portion of the NATO spending budget accounts for roughly 84% of the total NATO common-funded budget. NATO 2025 military budget stands at €2.37 billion ($2.75 billion).

The experts welcomed the EU’s decision to allocate €800 billion in loans to develop the militaries of its member states, but Executive Director of OPEWI—Europe's War Institute, Michael Benhamou, also warns that it “is primarily a strategic communication announcement that doesn't reflect a significant budgetary or political shift.”

Furthermore, the European defense preparation operates on a fundamentally different timeline than the immediate threat posed by Russia.

“Defense isn't something you improve over six months; it takes six to ten years and requires European cooperation,” Benhamou says, while adding that there is “a risk of ‘horizontal escalation’—escalation outside of Ukraine. That is very much possible at any moment and could take many forms and shapes.”

We bring you stories from the ground. Your support keeps our team in the field.

Answering whether an increased NATO contribution would improve the situation for the Alliance, the experts said “yes.” The current 2% threshold is deemed insufficient: Europe needs a minimum of 3-4% of GDP for defense, with Trump's suggested 5% being "realistic and necessary. " Meanwhile, Alberque warns that without fundamental reform in “NATO's military infrastructure, military capabilities, societal support, and international cooperation,” increased spending percentages won't provide meaningful defensive capability.

There’s also the issue of spending efficiency. The experts came to a consensus that Europe needs to take the Russian threat more seriously and manage its defense budgets more effectively, describing the current system as “wasteful and duplicative” while noting that the pace of practical change remains slow.

“There is a window of opportunity for Russia until 2030 because most decisions made in European defense will only have an effect in five years,” Benhamou said.

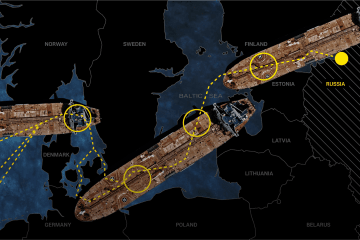

While Europe’s defense buildup moves on a longer timeline, Ukraine has already demonstrated how pressure can be applied in the short term—most notably through its campaign targeting Russia’s oil infrastructure, which has directly constrained Moscow’s revenues and ability to finance its war. Combined with Western sanctions, these strikes have amplified economic pressure on Moscow, forcing refinery shutdowns, disrupting fuel exports, and straining Russia’s domestic energy supply. It underscores that decisive measures taken now can matter as much as capabilities promised years down the line.

Weapon production and its stocks

Between late 2022 and mid-2024, Russian quarterly production rates substantially increased. The number of tanks went from 123 to 387 units, armored vehicles from 585 to 1,409 units, artillery guns from 45 to 112 units, and Lancet loitering munitions from 93 to 535 units per quarter.

However, about 80% of Russia’s increase in tanks and armored vehicles comes from modernising and refurbishing existing stockpiles, with only about 20% being new production units.

Russia accelerated its weapon production faster than it uses them, and is still building up reserves. It now produces about 250,000 artillery shells per month.

Europe is not close to matching those numbers. Germany, arguably the largest tank manufacturer in Europe, can produce 40-50 Leopard 2A8 tanks per year. Meanwhile, France churns out approximately 144 Caesar howitzers per year, and Europe manufactures 40-60 Taurus missiles.

Storm Shadow cruise missile production, which had been halted for about 15 years, resumed in 2025. Europe’s Storm Shadow missile inventory as of 2025 is estimated at 1,000 units, though significant quantities have been supplied to Ukraine, depleting these reserves.

Europe’s current artillery shell capacity is roughly 83,000 per month, though it is expected to reach 167,000 by the end of 2025. Accordingly, European stocks would be rapidly depleted in high-intensity warfare, especially since Russia, with China's help, can produce more artillery shells than the NATO bloc.

"Russia has successfully converted to a war economy, while Europeans have not. We lost three years,” Gormans says while discussing these numbers.

Experts also noted that Europe’s continued reliance on US weaponry could further complicate its defense preparedness.

“Europe will face significant weapon gaps in certain areas,” Eitvydas Bajarūnas, Ambassador-at-large for Hybrid threats in Lithuania, said, emphasizing that Europe doesn't have a replacement for American Patriot anti-air defense systems.

Gorman said that Europe can achieve the same weapon production rate in the next few years if the necessary political decisions are made. However, he added that "they have not decided yet." Still, he expressed confidence NATO air forces would destroy the Russian Air Force in days, in an air warfare confrontation.

“NATO's operational concept for a war with Russia involves sending hundreds of jets into Russian airspace on the first day,” he says. “This would completely disrupt Russian operations by destroying their forces far from the contact line.”

The nuclear arsenal

Despite Russia’s ever-present nuclear threats, Benhamou believes that the potential war with Russia would be conventional.

“Decision-makers are increasingly desensitized to their [nuclear weapons] presence and believe they have room to manoeuvre regardless, with nuclear threats barely factoring into their strategic calculations, ” he said.

Other experts concur. Nuclear weapons are mostly seen as a “threat, ” as a “scare tactic, ” and considered as “deterrents, ” with Rebecca Harms, the co-chair of the Greens/European Free Alliance faction, noting that they “play a crucial role in deterrence.”

“Nuclear weapons exist so that nuclear war will not happen,” she says. “All sides know that once they use them, the other side will also use them.”

Still, numbers matter.

Russia has about 5,977 nuclear warheads, of which about 4,500 are strategic. The European bloc, including France, Britain, and the US, has up to 1,000 nuclear warheads in total.

France has approximately 290 nuclear warheads

The United Kingdom has about 225 nuclear warheads.

The United States stations roughly 180 B61 nuclear bombs within Europe at several NATO bases in countries like Germany, Italy, Belgium, the Netherlands, and Turkey.

Moscow has systematically undermined the Non-Proliferation Treaty framework, withdrawing from key arms control agreements and accelerating its nuclear modernization programs.

According to a 2025 annual threat assessment by the US intelligence community, Russia is augmenting its nuclear forces with new capabilities, including nuclear air-to-air missiles and novel nuclear systems. Russia is also providing nuclear technology assistance to allies like Belarus and potentially Iran.

Are you ready to fight for your land?

Russia has 1.32 million active soldiers, while Europe's national armies have about 1.5 -1.6 million active personnel combined (NATO collectively has 3.42 million active military personnel).

The problem is that Russia has a massive mobilization potential of over 69 million estimated available manpower. While Kremlin may be running short of mobilization resources due to the meat-grinder tactics in Ukraine, If European NATO members "doubled or tripled their troop contributions," their combined forces would still not match Russia's potential army size.

This difference is critical, given that in conventional war, infantry plays a key role; however, even more critical is the society’s psychological readiness—the bravery and courage of the people to defend their country.

“War ultimately requires accepting death and sacrifice, and most European societies prioritize comfort and short-term pleasures,” Benhamou emphasizes. Putin has successfully convinced Russian elites and population that "violence brings value to Russia," while Europe lacks a mobilization mindset in the face of a threat, according to Benhamou.

Data substantiates his claims. While countries from the ex-Soviet bloc show a strong desire to fight for their land, with some 84% of Poles and 81% of Czechs, in Germany and Austria, the figure drops to 42% and 16% respectively.

The pattern is clear, according to Benhamou: "the further east you go, the more you find countries willing to make sacrifices because they understand the threat; the further west, the less you find that commitment."

Bajarūnas concurs with Benhamou’s assessment, adding that “the will to fight is very high" in Lithuania, a country on NATO's eastern flank.

“As you move west from Finland and Poland, the appetite to fight probably decreases,” he said. “I shouldn't criticize our friends in Spain, Portugal, or France, as they don't see the threat as imminent. But across the Eastern European flank, we are ready to fight.”

Meanwhile, Gormans adds that “Europe does not have programs to prepare people for the war. They understand that it's a priority, but they do not do it.” While this assessment broadly holds true, the past year has seen the first tentative steps toward addressing these gaps at the national level.

At the national level, several European states have begun taking steps to close critical gaps. In December 2025, Germany’s parliament approved legislation requiring registration for potential military service, aimed at addressing manpower shortages should voluntary recruitment prove insufficient. France announced a new voluntary military service for 18–25-year-olds in January 2026, launching in September with 3,000 recruits and expanding to 10,000 annually by 2030. Poland launched its largest-ever voluntary military training initiative in early November 2025, aiming to recruit up to 400,000 people by 2026.

The defense budget and NATO's weapons production are still not at the levels necessary to counter the potential Eastern Bloc aggression. More appropriate defense spending on weapons production and strengthening the military requires workable decisions that should be made today.

One such step came in December 2025, when NATO agreed on its 2026 common funded budgets, designed to directly support alliance readiness and capabilities by strengthening interoperability, crisis response, joint training, and capability development.

But even with recent increases, Europe's total defense spending roughly equals Russia's—but whether it is prepared for a wider confrontation involving coordinated action by Moscow and its allies remains unclear.

“War is unpredictable by nature,” says Benhamou. “It's not like business. It's about political will, the will of societies. You only discover your true character when facing it directly. Ukrainians learned this the hard way. Europeans will likely face the same harsh lesson soon.”

-29ed98e0f248ee005bb84bfbf7f30adf.jpg)

-206008aed5f329e86c52788e3e423f23.jpg)

-605be766de04ba3d21b67fb76a76786a.jpg)

-27ef304a0bfb28cb4215e5deede4a665.png)

-46f6afa2f66d31ff3df8ea1a8f5524ec.jpg)