- Category

- Anti-Fake

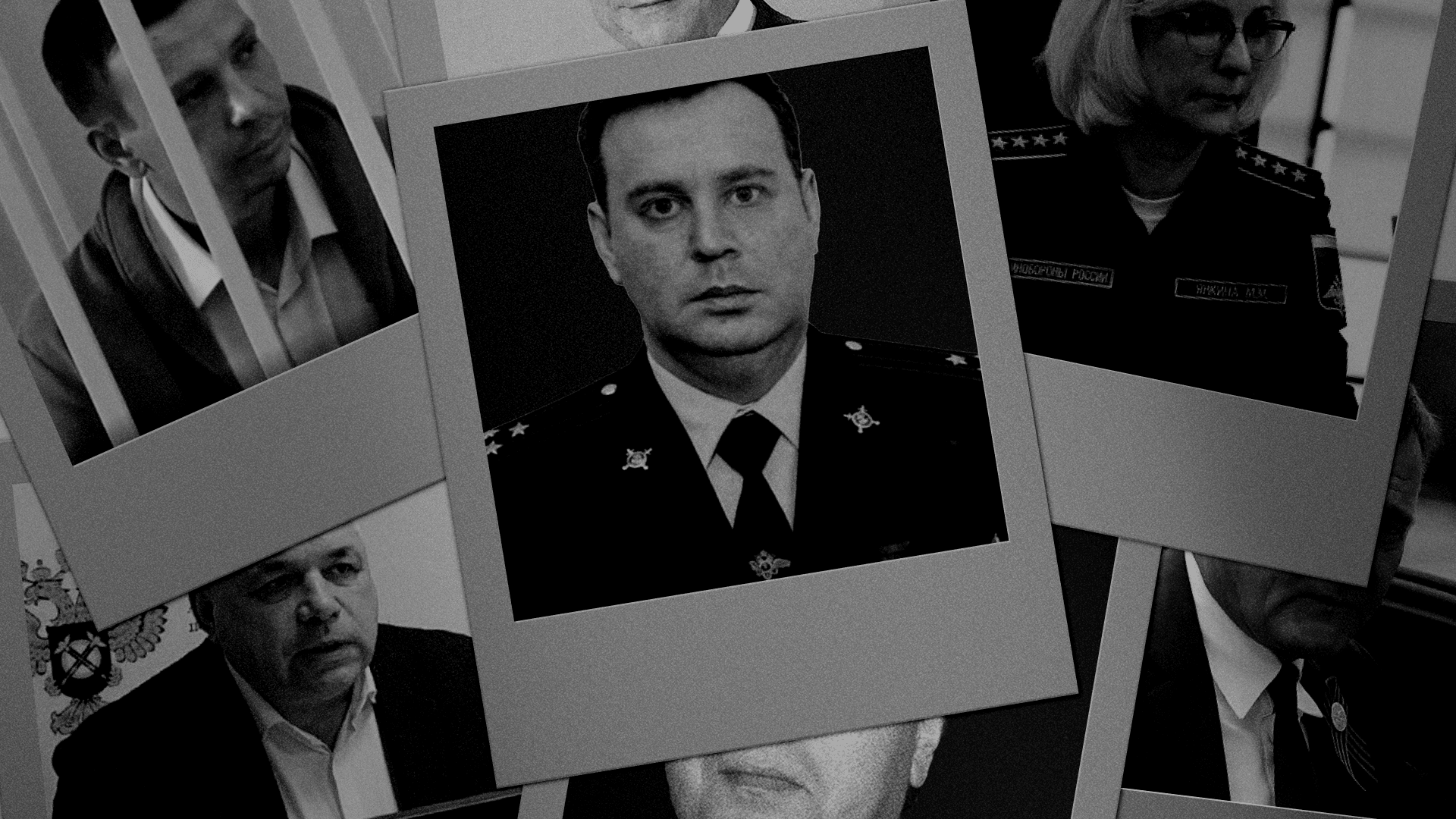

Why Russia’s Elites Keep Dying in Mysterious Ways

Amid Moscow’s collapsing economy, Russia’s top businessmen and officials are falling—literally and figuratively—under mysterious circumstances. Even the untouchables are vulnerable to a system in turmoil.

Another high-profile Russian executive was found dead in September 2025, reportedly by suicide—bringing the total to at least five this year and nearly 40 since Russia’s full-scale invasion began.

Alexander Tyunin, CEO of UMATEX, a Rosatom subsidiary, was found dead on the side of the road, near his car, with a hunting rifle and a suicide note allegedly citing depression. His death, however, has raised questions.

Just days earlier, Alexander Fedotov, a former transportation official in St. Petersburg, was found below the window of a Sheraton hotel at Moscow’s Sheremetyevo Airport, with the suspected cause of death being suicide.

Since Russia’s 2022 invasion of Ukraine, a string of officials, businessmen, bureaucrats, oligarchs, and public figures have died in unusual circumstances. The vast list of these deaths—which includes alleged defenestrations, suspected poisonings, suspicious heart attacks, and supposed suicides—has led to experts coining the term “Sudden Russian death syndrome.”

As Russia’s economy is plummeting, its elite is falling with it. Ukraine's drone strikes are crippling Russia’s energy sector, knocking out nearly 40% of its oil refining capacity, triggering its worst fuel crisis in decades.

The EU plans to implement tougher restrictions on Russia, targeting three key sectors: energy, financial services, and trade, which is likely to derail top Russian state corporations, like Gazprom, further. Most of the deaths are concentrated in these three of Russia’s most vulnerable sectors, the backbone Moscow cannot afford to lose.

Russia’s leader, Vladimir Putin, claimed in 2010 that Russia abandoned the Soviet-era “mokroye delo”—also called “wetwork” in the West—policy of assassinating turncoats. "Russia's special services don't do that," he said during a televised call-in, "as for the traitors, they will croak all by themselves.” Suggesting a grim fate for the traitors of his regime, potentially by suicide.

Are these really suicides? Maybe. Convenient? Definitely. Patterned? You bet.

Julianne Geiger

Researcher at Oilprice

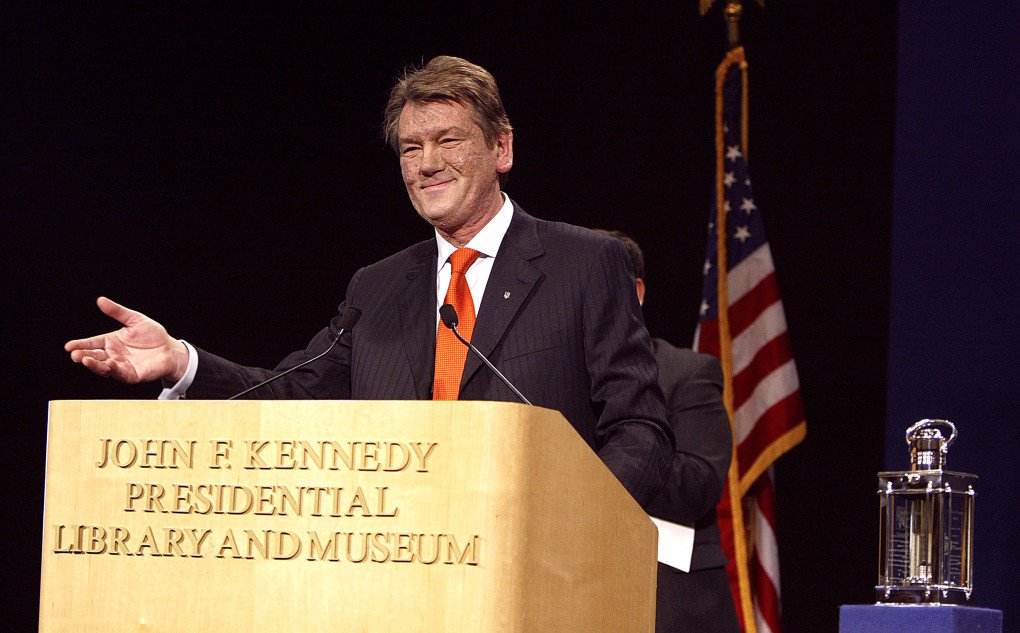

Russia has a history of using poisons to target critics. Novichok was used against a former spy in 2018 and Alexei Navalny in 2020. Dissident Alexander Litvinenko was poisoned with polonium in 2006, and Ukrainian president Viktor Yushchenko was poisoned with TCDD, leaving him disfigured. Journalist Anna Politkovskaya survived an FSB poisoning in 2004 but was later shot in Moscow.

The wave of sudden, unusual deaths since Moscow’s invasion of Ukraine has raised serious questions—from their timing and sector ties to the repeated methods and opaque investigations that follow.

Some were likely genuine suicides, but there is reason to believe that others were not. After all, Russia has set a historical precedent for this “Sudden Russian Death Syndrome” phenomenon, and the macabre list keeps growing at an exponential rate.

Russia’s corporate battle

Mikhail Rogachev, former vice-president of the Russian oil giant Yukos, plunged 110 feet to his death from a window at his home in October 2024. His body was reportedly discovered by an officer of Russia’s Foreign Intelligence Service (SVR) who claimed he found it while walking his dog.

Rogachev’s career was tied to one of Russia’s most dramatic corporate battles in history. Yukos, once the country’s fastest-growing private oil company, became the center of a decades-long confrontation with the Kremlin.

From 1996 to 2007, Rogachev served under Yukos owner Mikhail Khodorkovsky—once Russia’s richest man. Khodorkovsky openly criticized Vladimir Putin and financed opposition parties, a move that made him a political target. He was arrested on charges widely viewed as politically motivated, and Yukos was dismantled by the state in 2007.

Khodorkovsky was pardoned in 2013, but the legal war didn’t end there. In 2014, The Hague’s international arbitration court ordered Russia to pay $50 billion to Yukos’s former majority shareholders. The company also won $2.6 billion in damages from the European Court of Human Rights (ECHR).

Rogachev’s death adds another unsettling chapter to the saga of Yukos—a story that continues to symbolize the Kremlin’s clash with independent business and political dissent.

The Yukos example became a byword for what happens to those who dare to challenge Putin’s regime. As long as the oligarch’s interests remain subjugated to those of the regime, their fortunes would remain untouched. But those who oppose Putin or his political priorities would be destroyed.

Royal United Services Institute think tank RUSI

Deaths in Russia’s oil and energy sectors

Rogachev is just one of many deaths rocking Russia’s oil and energy sectors since Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine began.

January 2022, a month before full-scale war broke out, Leonid Shulman, head of Gazprom Invest’s transport service, found dead in his St. Petersburg country house bathtub, followed in February by Alexander Tyulyakov, Gazprom deputy director, hanged in his suburban garage.

April 2022 brought two gruesome alleged family murder-suicides: Vladislav Avaev, vice president of Gazprombank , and Sergey Protosenya, former Novatek manager, were killed with their wives and daughters—Avaev in Moscow, Protosenya in a Spanish villa.

A killer comes up with his own method when he’s ordered to take out a family. Similar methods but each slightly different—an axe here, a gun there. They're dead all the same. Once perhaps, twice a coincidence. This is not a coincidence. It's not suicide.

Russian banker

In May 2022, Alexander Subbotin, ex-Lukoil board member, died of acute heart failure in Mytishchi; July saw Yuri Voronov, founder of Gazprom subcontractor Astra-Shipping, shot in a swimming pool in Leningrad Region.

August claimed Ravil Maganov, Lukoil chairman, falling from a Moscow hospital window; by December, Oleg Zatsepin, Kogalymneftegaz director, was found dead in his office.

February 2023: Vyacheslav Rovneyko, Urals Energy co-founder and former partner of Boris Yeltsin’s son-in-law, died at his Rublyovka estate. October 2023: Lukoil chairman Vladimir Nekrasov died of heart failure.

March 2024: Lukoil VP Vitaly Robertus found dead in his Moscow office. July 2025: Andrey Badalov, Transneft VP, fell from his Rublyovskoye Highway apartment.

Striking similarities with the string of deaths of senior executives at Russian oil and gas companies in recent years….This level of risk could have been sufficient to justify a murder staged as a suicide.

Anti-corruption expert

Deaths of Russia’s elite

In December 2022, Pavel Antov, a representative of Putin's United Russia party and deputy in the Vladimir region's local parliament, fell to his death at a hotel in India. Just two days before, Vladimir Bidenov, another member of his party, died from an apparent heart attack.

Antov was ranked the richest parliamentarian in the country in 2019 by the Russian edition of Forbes magazine. In June 2022, Russian media published a WhatsApp message stating that Antov described a Kremlin missile attack on Ukraine as terrorism, prompting Antov to publicly deny these allegations on Russia’s VK social media network.

On February 4, 2025, two high-ranking officials fell out of windows on the same day—Artur Pryakhin, head of the Federal Antimonopoly Service (FAS), and Alexei Zubkov, a colonel in the Investigative Committee and deputy head of the forensic department.

Pryakhin was found near the office building, and according to Russian reports, fell from a fifth-floor window, allegedly leaving a suicide note for his wife. He served for around 15 years in the Ministry of Internal Affairs' economic crime units, investigating high-profile cartels.

Zubkov fell from a window of the Investigative Committee's Forensic Center on Stroiteley Street in Moscow. While he suffered moderate injuries, Russian media reports that he remained conscious after the fall and said that he was in the bathroom, alone, and didn’t remember what happened next.

Deaths of high-ranking businessmen

On September 8, 2025, in the Kaliningrad region, authorities discovered the decapitated body of Alexei Sinitsyn, a general director of NPK Khimprominzhiniring, a subsidiary of the state-owned nuclear giant Rosatom.

In July 2025, Roman Starovoit was dismissed as Russia’s transportation minister just hours before he reportedly took his own life in a parking lot outside Moscow, with a pistol presented to him as an official gift at his side.

The date of (Starovoit’s) death, and the time of death, we don’t know. Before Putin’s signature? Before the signing of this firing decree? There are too many questions regarding all this.

Former executive director for Transparency International Russia

Before Starovoit served as transport minister, he was the governor of the Kursk region, which Ukraine’s forces attacked in August 2024, humiliating Russia. He was reportedly being investigated for embezzling state funds allocated for building fortifications in Kursk.

His successor, Alexei Smirnov, was arrested and charged with fraud. Reports alleged that Starovoit’s superior associates could have ordered his killing to avoid exposure.

Dan Rapoport, a well-known and effective Kremlin critic, Russian businessman, and international investment banker, was found dead on August 14, 2022, on a pavement outside an apartment building in the US.

He was reportedly wearing orange flip-flops and a black hat, and had a cracked phone, headphones, and $2,620 in cash on him, but no wallet or credit cards. Mr Rapoport was an early supporter of jailed opposition leader Alexei Navalny, and had many connections in the elite of Washington, D.C.

In my experience, more often than not, if a wealthy person dies in suspicious circumstances, the explanation is sinister, not something innocent when it comes to Russian people.

Bill Browder

Formerly Moscow-based American financier

Vadim Stroykin, a pro-Ukrainian Russian musician, fell from the window of his tenth-floor apartment in February 2025. He was reportedly being investigated for donating to the Ukrainian Armed Forces.

In August 2025, the sudden deaths of Dmitry Osipov, chairman of Uralkali , and Mikhail Kenin, founder of construction giant Samolet, also raised questions.

A system in crisis

In the shadow of war, Russia's elite are falling—literally and figuratively, and the pattern and frequency are undeniable. This wave of deaths of those who oppose the Kremlin is hardly surprising, but also highlights the unravelling of a system that once promised protection for its loyalists.

The deaths of Russia’s elite since the full-scale invasion aren’t just victims of coincidence—they sit atop industries now under unimaginable pressure. From the halls of Gazprom and Lukoil to the boardrooms of government officials, Russia’s wealthy are caught between crippling sanctions, disrupted trade, and Kremlin demands for loyalty and results.

Ukraine’s “Kinetic Sanctions” are crippling the oil industry that fuels Russia’s war machine. pic.twitter.com/Lo1CXMO1D3

— UNITED24 Media (@United24media) October 2, 2025

The EU's stringent sanctions have severely impacted the financial stability of Russia's elite, with an estimated loss exceeding $38 billion in 2022 alone. Russia’s National Wealth Fund (NWF)—its primary financial cushion built on oil and gas profits—has been drained, while a growing number of elites in the oil sector, the backbone of its war machine, are falling.

This economic strain, coupled with escalating political pressures, has likely intensified internal conflicts, leading to a climate of fear and distrust among the ruling class. The recent death of Roman Starovoit underlines the profound shifts occurring within Russia's political system, where perceived disloyalty or failure can result in fatal consequences.

In Russia's Khabarovsk Krai region, even with the 10 liter limit on fuel purchases, only 10% of stations now have anything to sell.

— Jay in Kyiv (@JayinKyiv) October 5, 2025

It's getting worse. pic.twitter.com/7Z301X79zb

Are Russia’s elite all dead by suicide?

Russia has an extremely low life expectancy, even lower than North Korea, according to Worldometers. The nation also has a well-documented rate of alcoholism, along with one of the highest suicide rates globally; therefore, undoubtedly, some of these deaths could have been genuine suicides.

However, even pro-Kremlin Sergei Markov, director of Russia’s Institute of Political Studies, on record suggested that Starovoit was murdered. “It seems to me that those who eliminated him—that is, those against whom he could have testified after his arrest—are trying to hide his real murder by using the suicide version.”

Until recently, it was still possible to leave power in Russia, resign, albeit with difficulty, and flee the country. Since 2022, it has become almost impossible. “Voluntary withdrawal from the system can be considered treason, and as Putin has repeatedly made clear, traitors do not live long,” Alexandra Prokopenko of The Carnegie Endowment wrote.

Russia expert, Alexander Baunov, argues that there are three theories to these deaths. Suicide out of conscience or out of fear, and thirdly, liquidation as punishment. He argues that Starovoit’s death is a turning point for the elite, adding that “officials won't find the third theory so improbable…no matter how much the investigation insists on suicide, they'll believe their own fears more.”

Whether they were silenced or driven to despair doesn’t change the pattern: in Putin’s Russia, retirement often ends in a morgue. Leaving the system alive is becoming the exception, not the rule.

Former Yukoil owner and Russian political prisoner

In a system where mistakes are punished and visibility is a liability, wealth and influence offer no shield. The collapse of these high-stakes businesses has turned power into peril. The deaths of these figures are a stark reminder of the perilous intersection between economic sanctions and political instability, and that in today’s Russia, even the untouchable are vulnerable.

-29ed98e0f248ee005bb84bfbf7f30adf.jpg)

-46f6afa2f66d31ff3df8ea1a8f5524ec.jpg)

-29a1a43aba23f9bb779a1ac8b98d2121.jpeg)

-4d7e1a09104a941b31a4d276db398e16.jpg)

-3db1bc74567c5c9e68bb9e41adba3ca6.png)