- Category

- Life in Ukraine

Would Your Home Survive Russia’s War? Hard Lessons From Ukraine

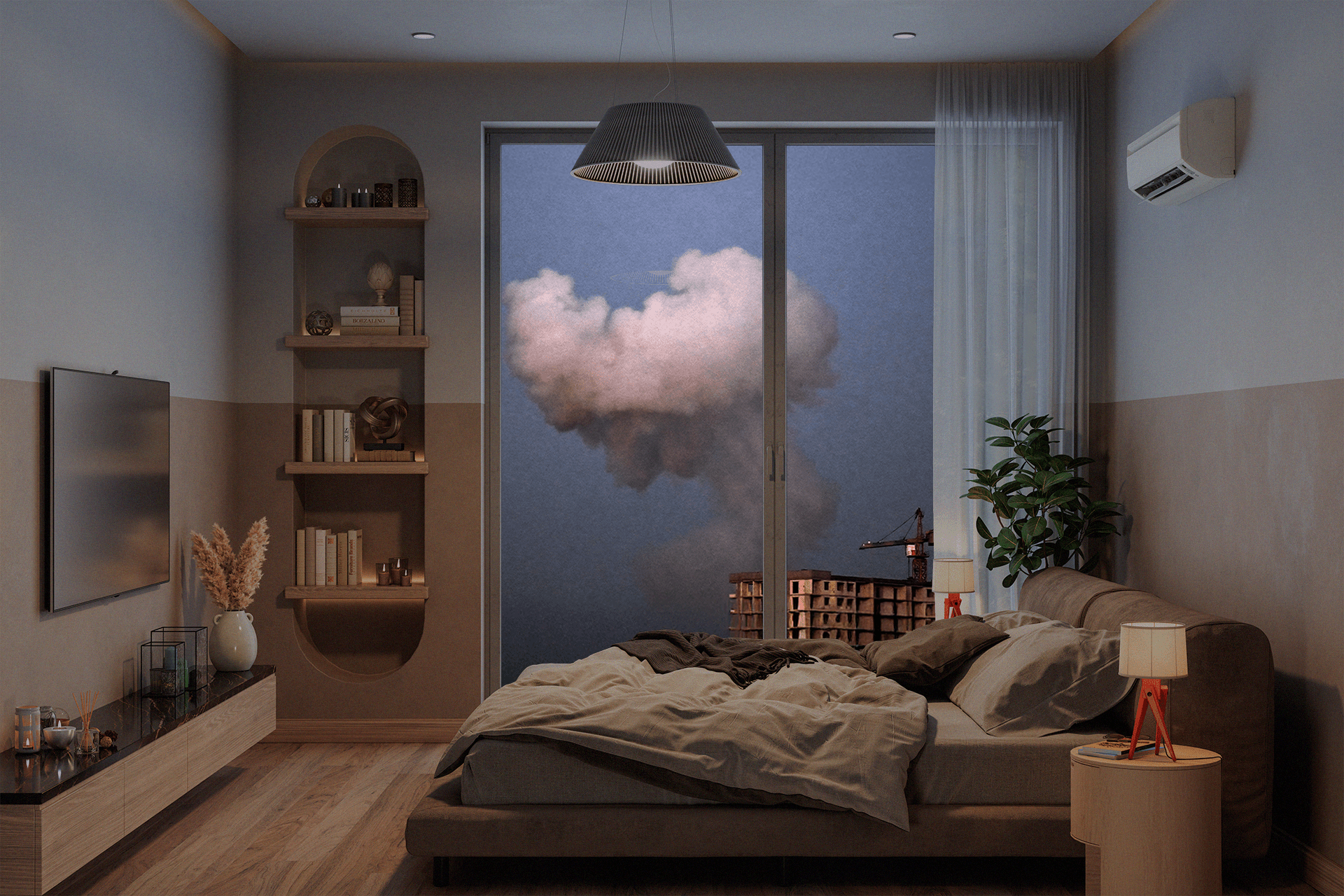

A Kyiv penthouse with panoramic windows once embodied success. Now, it’s where people jolt awake to air raid sirens, counting the seconds: will they make it to a shelter, or is it safer to stay in the bathroom? Russia’s relentless bombardment has radically reshaped what Ukrainians call comfortable housing. Here are the main lessons.

Ukraine’s housing stock totals more than 10.2 million residential buildings. Before Russia’s full-scale invasion in 2022, the country had a population of about 42 million; today, it is closer to 33 million. Over the past three years, Russia has destroyed some 236,000 homes, says the Kyiv School of Economics. Ukrainians are no strangers to the reality of losing their homes to Russia’s war.

Your wartime housing checklist:

What floor do you live on?

What kind of windows do you have? Is any room in your apartment separated from the street by two walls?

What’s located next to your building?

Do you have a basement? How many exits does it have, and is there ventilation and mobile service?

Where does your electricity come from?

Let’s break it down.

Fear of heights

As in cities worldwide, upper-floor apartments were once the most coveted in Ukraine. They offered better views, less street noise, and no neighbors peeking in. Today, however, penthouses are among the least desirable options for several reasons.

First, during an air raid alert, reaching a shelter takes more time. Ukraine’s Urban Coalition from Ro3kvit calculated that descending from the sixth floor takes two and a half minutes. Considering that, for example, a Russian Kinzhal missile can reach Uzhhorod, Ukraine’s farthest regional center, in just over six minutes, and Kharkiv in less than two. That margin of time can be critical.

Second, Russia’s attempts to cripple Ukraine’s energy grid. Ukrainians have already endured two winters of rolling blackouts, which meant trudging up countless flights of stairs when elevators stood still.

Third, the higher you live, the greater the chance of being hit by a Russian missile or drone. That said, it’s important to note that modernized Iranian “Shahed” drones and some missiles now rip through entire buildings from top to basement, literally flattening even nine-story blocks.

This brings us to another key factor.

Dungeons and brag-ons

Ukraine’s subway systems exist only in Kyiv, Kharkiv, and Dnipro. Apartments near metro stations were always in demand for convenience. Now the metro doubles as a reliable bomb shelter. Most stations are deep underground, spacious, and clean. During alerts, they become mass shelters—on August 28, for instance, over 24,000 people took cover in Kyiv’s subway, including 1,800 children.

Large underground parking garages or other buried structures can serve as alternatives.

For parents, the metro has also become an educational space. In 2023, classrooms were set up directly on Kharkiv’s subway platforms. These “metro-schools” still operate at six sites across the city. Another approach is being built above ground: Kyiv is finishing a $7 million school with a fully equipped shelter for 1,300 students.

38 underground schools are planned for the Kharkiv region by the end of 2025. Similar schools are already functioning or under construction in the Zaporizhzhia, Kherson, Sumy, Dnipropetrovsk, Mykolaiv, and Chernihiv regions. 150 underground schools will open nationwide by year’s end, enabling children to return to in-person learning, says Ukraine’s Education Minister Oksen Lisovyi.

Dangerous neighbors

Living next to a factory used to mean noise or pollution. Today, it can mean death. Military sites, power stations, strategic enterprises, rail hubs, TV towers—all raise the risk of strikes.

Before Russia’s full-scale invasion, Kyiv neighborhoods like Lukianivka or Solomianskyi, both near the city center, were seen as desirable places to live. Now they are frequent targets because of nearby factories. Residents of Lukianivka have even designed a grimly ironic logo for their district: a missile paired with the slogan, “What doesn’t strike us flies past us.”

By contrast, less fashionable residential suburbs may now be safer and more desirable simply because they lack risky neighbors. Yet, for Russia, almost anything can appear a “threat.” Printing houses, warehouses of humanitarian aid, even a coffee machine factory run by an American company, have been bombed.

Which brings us to location.

Location, relocation, salvation

That coffee machine factory, operated by Flex, was located in Zakarpattia, Ukraine’s westernmost region. Uzhhorod, the local hub, is 1,300 km from Moscow but closer to Berlin. Still, missiles reach it too. No part of Ukraine is safe—the only question is how long it takes for drones or missiles to arrive.

Nevertheless, western Ukraine has become more attractive. Cities like Lviv, Ternopil, Ivano-Frankivsk, and Chernivtsi are experiencing a housing boom. For the first time ever, Kyiv has lost its lead: in January 2025, the average price of new housing in Lviv was 5% higher than in the capital.

Overall, prices in eastern and central regions are dropping, while western regions surge. In Zaporizhzhia, the average apartment costs nearly four times less than in Lviv.

The decisive factor is proximity to Russia. Often, the closer the region, the cheaper the housing. This is directly tied to the intensity of the Russian attacks and the extremely limited time residents have to reach safety. In frontline cities such as Kharkiv and Sumy, that window is measured in minutes—or even seconds. Sumy, a city of 270,000, lies within range of Russian tubed artillery, leaving virtually no chance to take cover.

Western Ukraine offers relative safety, though it is still targeted by long-range suicide drones and missiles. Moscow is also upgrading its arsenal. Shahed drones that once traveled at 170–200 km/h are now being replaced with jet-powered models capable of reaching 500 km/h. In just three summer months of 2025, Russia launched 15,933 Shaheds against Ukraine.

The closer Russian forces advance, the less time drones and missiles need to reach even distant cities, as Russia actively turns the land it occupies into launchpads. This is why stopping Russia’s offensive is a matter of absolute urgency.

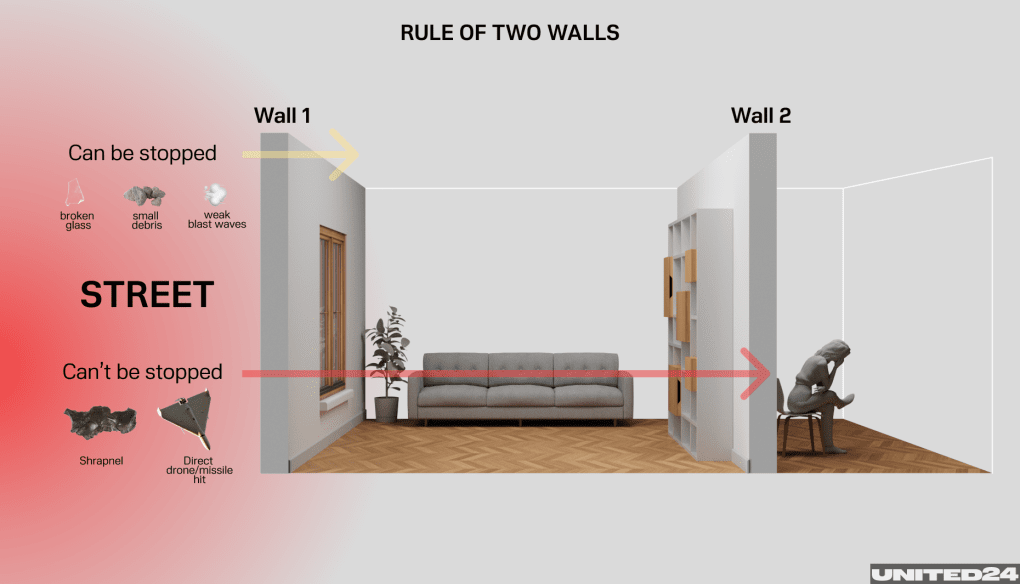

Construction innovations

Surveys show only about 15% of Ukrainians go to shelters during air raid alerts, which can happen several times a day and last for hours. Most stay in bathrooms or corridors, relying on the “two walls rule”: having two layers of brick or concrete between you and the street. But with Russia developing increasingly powerful drones and more lethal shrapnel, this rule no longer offers much safety.

One solution is in-apartment safe rooms. These may look like closets or pantries but are reinforced with rebar and concrete, have blast-resistant doors, and include emergency beacons. They can’t withstand a direct missile hit, but may save lives from debris or shockwaves.

The first residential complex in western Ukraine with built-in safe rooms—Lviv City—is under construction, designed with input from emergency services and modeled on Israel’s experience with mamads, reinforced rooms common in Israeli homes.

Some Ukrainian companies have gone further. Resq Pods, for example, developed protective capsules that can withstand a 40 kg TNT blast, fire, and a two-story fall. They include ventilation, emergency signaling, and food and water supplies.

Bottom line

For the past three and a half years in Ukraine, what matters is not which floor has a view of the Dnipro, but how fast you can reach a shelter. Not how much light fills a room, but whether the room can withstand a strike. A “prestigious complex” in the city center no longer means safety. Instead, safety means distance from critical infrastructure, access to a real shelter, and independent power sources.

Are there strategic targets nearby? Do you live on a high floor? How long will it take to reach the basement without an elevator? Is the basement safe, with a backup exit and ventilation? How will you charge your phone without central power? Will it even work from inside the shelter?

Ukrainians keep living. They buy, sell, and rent. But the question, “Is this apartment safe?” is now one of the first in any conversation with a realtor. In a country where sirens are a daily routine, housing is no longer just a roof over your head. All too often, it is the line between life and death.

-554f0711f15a880af68b2550a739eee4.jpg)

-9a7d8b44d7609033dbc5a7a75b1a734e.jpeg)