- Category

- War in Ukraine

How Long Would it Take Europe to Launch an Effective Air Defense System From Scratch?

The Russian drone attack on Poland showed that NATO must prepare for the modern challenges of warfare—in particular, adapting to drone warfare, which Russia has long used against Ukraine.

Russia launched more than 20 drones toward Poland on September 10. There were no casualties. However, it quickly became clear that such mass attacks pose a serious threat to any country: the world has never fought like this before.

“Ninety-two drones were heading for Poland,” Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy said at a briefing on September 27. “We shot them down over Ukraine, of course. One could say they were aimed at us, but we see the direction and, as they say, the choreography of that flight. So, we believe 92 were launched. We shot them all down. Nineteen, we believe, reached Poland. Four were destroyed by the Poles."

To shoot down 4 drones, Poland had to scramble fighter jets, additional NATO forces were engaged, and AIM-9L Sidewinder missiles costing $450,000 each were used. More than $1.2 million worth of missiles were fired.

In this case, cost does not matter: each Shahed drone can cause enormous damage. In Ukraine, they attack residential buildings, energy infrastructure, factories, production facilities, shops, and destroy people’s personal property. Destroying the target, no matter the cost, is critical.

But the real question is: what happens when it’s not 20 drones, but 700?

Israel has one of the most powerful air defense systems in the world, but when Iran attacked the country with 300 rockets and drones, allies still had to scramble their air forces—US and European fighter jets joined the interception.

Here, Ukraine has a unique experience: 500–600–700 drones and missiles of different types can simultaneously attack vast areas of Ukraine from all directions. Covering such a scale with air defense is an enormous challenge. Fighter jets alone, whether F-35s or F-16s, are not enough. Especially since the enemy constantly changes tactics and adapts drones. Moreover, attacks can last 4–8 hours, with Shaheds circling near targets and waiting for the best moment to strike. Fighter jets cannot stay airborne that long—they need refueling.

This is why countering mass drone attacks is a challenge for any country. The UNITED24 Media team explains how Ukraine built its system, and why even with the most modern technologies—many of which were developed during the war itself—it may still not be enough.

The main challenge: mass attacks

Shaheds are evolving. Russia watches how Ukraine adapts and upgrades its weapons accordingly. So, what is a Shahed today?

It’s a drone that can reach speeds of 500–600 km/h, fly 2,500 km, and stay airborne for hours. It carries a warhead of about 50 kg, and dozens are often used together to cause serious damage. Today’s models have remote control, electronic warfare protection, and even local SIM cards to help navigate.

If the country has the right tools, a single drone can be detected and shot down by a fighter jet or air defense system. But it’s different when hundreds are launched simultaneously. Alongside them, Russia also launches decoys—so-called Gerans—which don’t carry warheads but distract defenders.

Countering hundreds of drones at once requires vast resources and diverse defenses. Ukraine has been building such a system for three years.

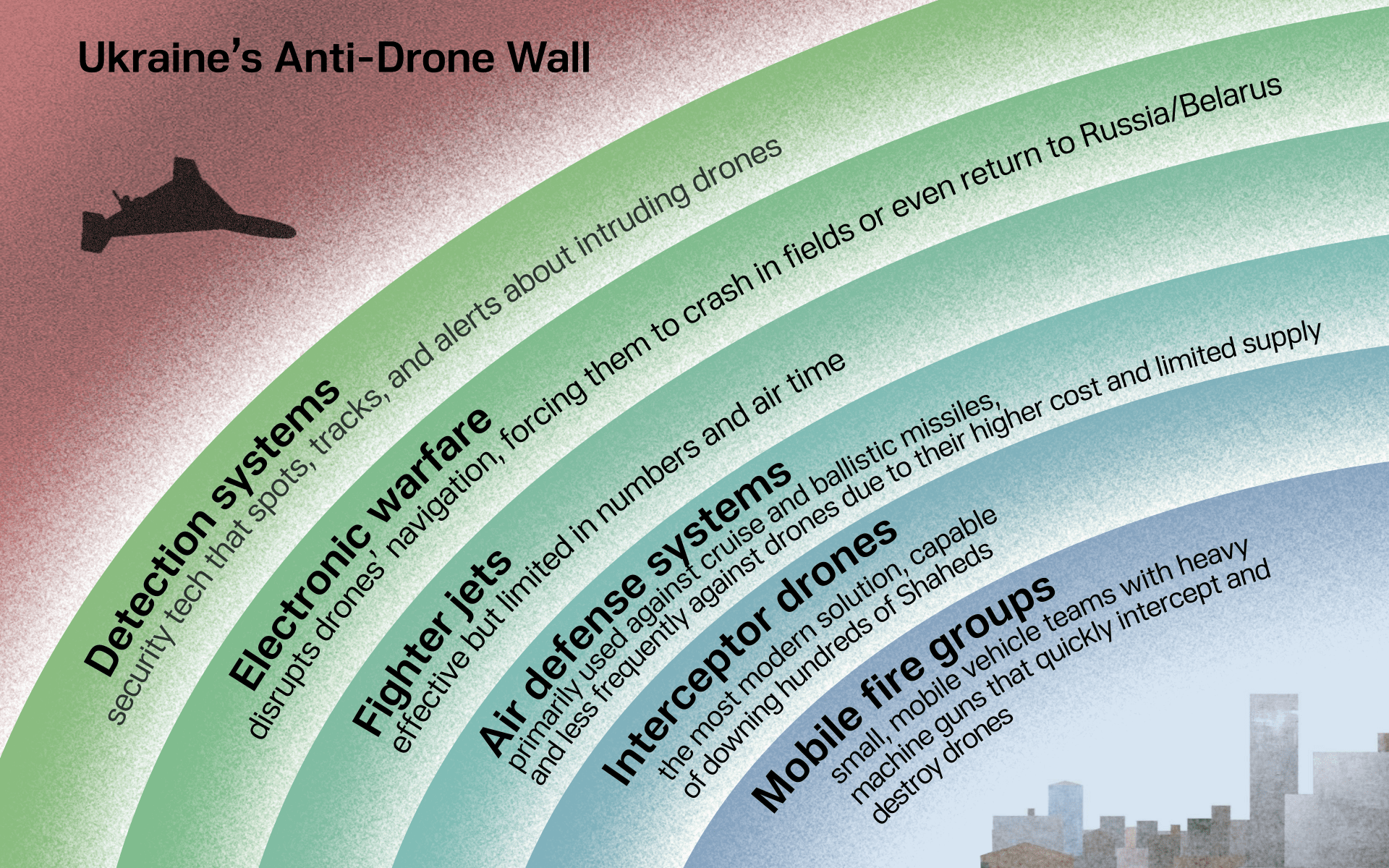

Multi-layered defense

It’s not enough just to shoot down drones—they must be destroyed before reaching populated areas. Falling debris can also cause severe damage. In Poland’s case, debris damaged a car and a house roof. With hundreds of drones, debris can spark fires in apartment blocks, destroy property, injure, or kill. So the top priority is destroying drones well in advance.

Ukraine’s system has several layers:

Detection systems: continuously improved throughout the war.

Fighter jets: effective but limited in numbers and air time, and dangerous, Ukraine has lost several aircraft and pilots in such missions.

Air defense systems: SAMP-T, Patriot, NASAMS are mostly used against cruise and ballistic missiles, and less often against drones. The problem isn’t only cost, but also supply: only about 1,000 Patriot missiles are manufactured annually, while Russia launched 16,000 Shaheds in one summer. Some short-range systems, like Germany’s Gepard, are used for drones.

Interceptor drones: the most modern solution, capable of downing hundreds of Shaheds. They are fast and can chase drones mid-air. The challenge is scaling production—just six months ago, there were hardly any; now, Ukraine needs to produce 200–300 daily. But Russia is also making its drones faster.

Mobile fire groups: once crucial in defending cities, but becoming less effective as Shaheds now fly higher and faster. Interceptor drones are taking their place.

Electronic warfare (EW): disrupts drones’ navigation, forcing them to crash in fields or even return to Russia/Belarus. In response, Russia upgrades its navigation and installs local SIM cards.

Ukraine’s layered defense has proven effective. For example, on September 25, 150 of the 176 drones launched were shot down. On most days, 80–95% of drones are intercepted.

The need for scale

The biggest challenge of air defense is volume. Each Patriot system has a finite number of missiles, which must be reloaded after use. Another factor is geography: Ukraine is huge, with multiple large cities. Protecting them all requires dozens of Patriot systems, hundreds of other air defenses, and thousands of mobile fire teams. Russia doesn’t just attack Kyiv, Kharkiv, or Odesa—missiles and drones strike across the country.

One day, 500 drones may target the capital; the next, Lviv near the Polish border; then Kharkiv, just tens of kilometers from Russia. Defense systems must be everywhere. That’s why Ukraine constantly asks Europe and the US for more air defense systems and missiles. A striking example: in February 2024, Ukraine downed 11 Russian fighter jets in a single month. Reportedly, Kyiv had moved a Patriot system close to the frontline to reduce pressure from Russian aviation—and it worked.

Today’s urgent need is interceptor drones. Russia now produces over 300 Shaheds per day, so Ukraine must at least match that pace—ideally outpace it—by scaling production and improving drone speed and performance.

All of this must work together, as a continuous system, not a one-time project. Russia constantly upgrades its killing technology, so defense must evolve just as quickly.

Ukraine has been building its system for three years and continues to do so. Poland, the Baltic states, and Romania—already under Russian drone attack—must prepare for the war of the future. Kyiv is ready to share its expertise and even export its own cutting-edge systems to partners, says Zelenskyy. That could significantly shorten the time needed to prepare their defenses.

Given Russia’s industrial scale-up of Shahed-type drones—now measured in the thousands per month—Ukraine and its allies must consider not only how to intercept attacks but how to degrade the factories and supply chains that sustain them. Denying Moscow the capacity to mass-launch suicide swarms is a defensive step: it reduces future civilian risk across Europe and shortens the war of attrition that Ukraine is forced to fight. And Ukraine’s June 15 strike on a facility in the city of Yelabuga, Tatarstan, where the Russian “Albatross” plant was serially manufacturing drones based on Iranian technology, shows that it is possible.

-457ad7ae19a951ebdca94e9b6bf6309d.png)

-29a1a43aba23f9bb779a1ac8b98d2121.jpeg)

-605be766de04ba3d21b67fb76a76786a.jpg)

-0c8b60607d90d50391d4ca580d823e18.png)

-76b16b6d272a6f7d3b727a383b070de7.jpg)