- Category

- World

The Global Ripple Effect: Why Lifting Sanctions on Russia Would Invite a Wider War

Lifting sanctions on Russia is being floated in peace talks—but history, and the Kremlin’s repeated behavior toward Ukraine and other countries, suggest it could trigger future escalation. Without sanctions, Russia gains money and technology to wage more wars.

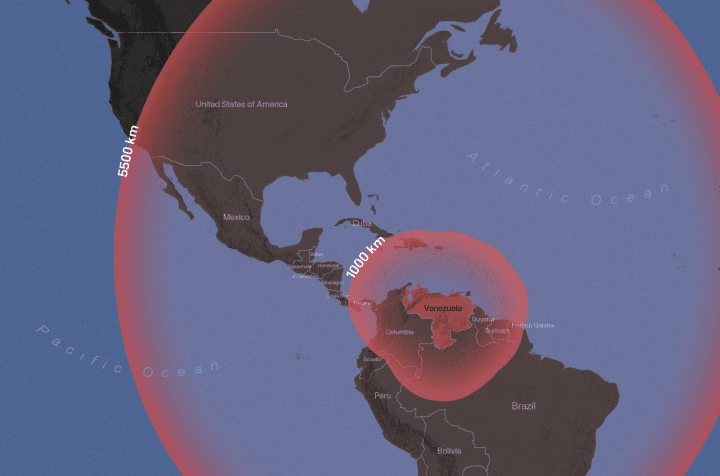

On the night of November 21, 2024, a Russian Oreshnik missile launched from the Kapustin Yar test site struck the Ukrainian city of Dnipro. Ukraine does not possess air defense systems capable of shooting down such weapons. This was an intercontinental ballistic missile capable of carrying a nuclear warhead—a medium-range missile with an approximate reach of 5,500 kilometers.

Though this is a new weapon, it appears to be based on Soviet-era designs. Its foundation seems to be the RS-26 Rubezh, which has a range of 5,800 kilometers. Development and testing began back in the early 2010s.

Only one point here is truly illustrative: in 1987, the United States and the Soviet Union signed the INF Treaty—eliminating intermediate- and short-range missiles. The Kremlin violated it, and in 2019, the treaty, which had been in force for 30 years, collapsed. In 2025, Russian politicians say the Oreshnik could be deployed to Venezuela, its 5,500-kilometer range allowing it to strike 80% of US territory. All of Europe is under threat.

At times, Russia’s war against Ukraine may seem like a regional conflict. Yet Moscow has repeatedly shown it is not: more than 20 Shahed drones entered Polish airspace in the summer of 2025—an obvious targeted provocation. A Shahed’s range is 2,500 kilometers; from Kaliningrad, it can reach most major European cities. Today, Russia is producing 300 of these drones every day.

Sanctions are crippling the Kremlin’s ability to wage war

The sanctions imposed on Russia are not aimed at ordinary Russians, nor are they intended to prevent them from living normally, working, or creating. Their primary goal is to stop Russia’s war machine from expanding. Today, the Kremlin spends more on the war than on social programs, education, and healthcare combined. Men who go to war receive enormous bonuses by Russian standards; the country is drowning in payouts for service, death, and injury — billions of dollars spent each year to attract new recruits and then write them off.

Moscow has drained its entire National Wealth Fund—money meant to build Russia’s future. Today, those funds are being used to destroy Ukrainian cities. For the Kremlin, every expenditure now serves the war.

Sanctions also restrict Russia’s access to technologies developed in Europe, the United States, and Asia. Nearly all modern Russian weapons rely on components sourced from around the world; without them, Russia would be unable to build missiles, fighter jets, or submarines. Sanctions reduce the flow of foreign components to Russian factories—and in some cases, cut it off entirely.

Russia’s oil sector—the backbone of its war financing—is also collapsing under the weight of sanctions. By late 2025, Russia’s oil revenues had fallen by $25 billion, with Urals crude selling for barely half the assumed budget price. Ukrainian strikes on refineries and ports, combined with sanctions on major producers like Lukoil and Rosneft, have forced Russia to offer deep discounts, reroute tankers through costly Arctic detours to reach China, and watch hundreds of millions of barrels sit unsold at sea. These trends show that energy sanctions are among the most effective tools for choking Russia’s ability to finance its war.

Russia’s expanding military reach

Washington understands the Russian threat well. The New York Times, citing sources, reports that chief US negotiator Daniel Driscoll warned European diplomats that Russia is rapidly increasing missile production and stockpiling enough weapons to alter Europe’s security landscape.

Today, Russia is the world leader in producing tanks, missiles, drones, and artillery shells. Its ally, North Korea, has repurposed its military factories to supply Russia. Rail lines have become lifelines—tens of thousands of freight cars moving weapons nonstop, destroying Ukraine today and potentially moving farther tomorrow.

Hybrid warfare has already turned the Baltic Sea into a zone of constant tension and heightened military activity. Transport aviation and commercial shipping are under threat. Unknown drones have become a new reality at European airports and military sites. Russia is expanding its presence in the Arctic and openly discussing the need to seize Svalbard.

European capitals are now openly talking about the possibility of a Russian attack and preparing for potential defense. Sanctions are a means of containing Moscow’s ambitions not only toward Ukraine, but toward other regions as well. One example is Iran.

History shows the cost of appeasing aggression

For many years, Iran has spoken of building military power, developing missiles and drones, and strengthening its network of proxies. Yet within two years, Israel—backed by its allies—destroyed nearly all proxy military capabilities and carried out several targeted strikes on Iran’s military infrastructure with US support. Israel, however, has the direct backing of allies and a strong military of its own.

After Russia invaded Ukraine and attempted the annexation of Crimea in 2014, the international response was limited—sanctions were imposed, but they were neither broad nor deep. Critical sectors, such as energy exports and high-tech imports, were left largely untouched. As a result, the Kremlin had nearly eight years to adapt, stockpile weapons, modernize its military, and redirect its economy toward war. The consequences of that restraint are now visible across Ukraine and even the rest of Europe.

Sanctions, by design, work gradually: they restrict revenues, undermine supply chains, and strain state finances over time rather than delivering an immediate shock. The effect is cumulative, and after nearly three years, the pressure is finally producing measurable results. Undoing sanctions now would unravel years of deliberate economic containment at the very moment it is beginning to limit the Kremlin’s ability to sustain the war or prepare for wider aggression.

Ultimately, one must understand that lifting sanctions on Russia would signal impunity for its actions. This has happened before: in 1938, the UK and France agreed to hand part of Czechoslovakia to Hitler. Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain did not receive a Nobel Prize for that decision. Instead, a year later, Europe plunged into the largest war in history.

-29a1a43aba23f9bb779a1ac8b98d2121.jpeg)

-605be766de04ba3d21b67fb76a76786a.jpg)

-88e4c6bad925fd1dbc2b8b99dc30fe6d.jpg)

-206008aed5f329e86c52788e3e423f23.jpg)

-7ef8f82a1a797a37e68403f974215353.jpg)

-554f0711f15a880af68b2550a739eee4.jpg)