- Category

- Culture

“F*ck, It Wasn’t Supposed to Happen Like This”: How a Ukrainian Surgeon Became an Iconic War Photographer

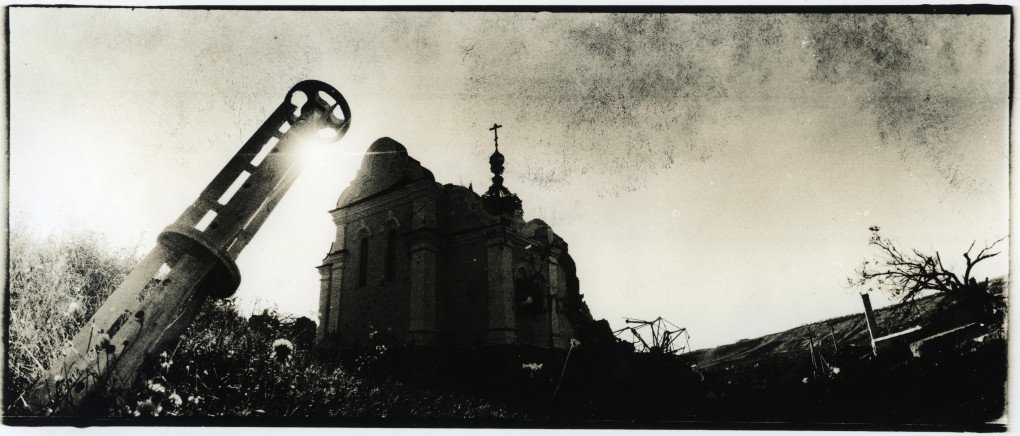

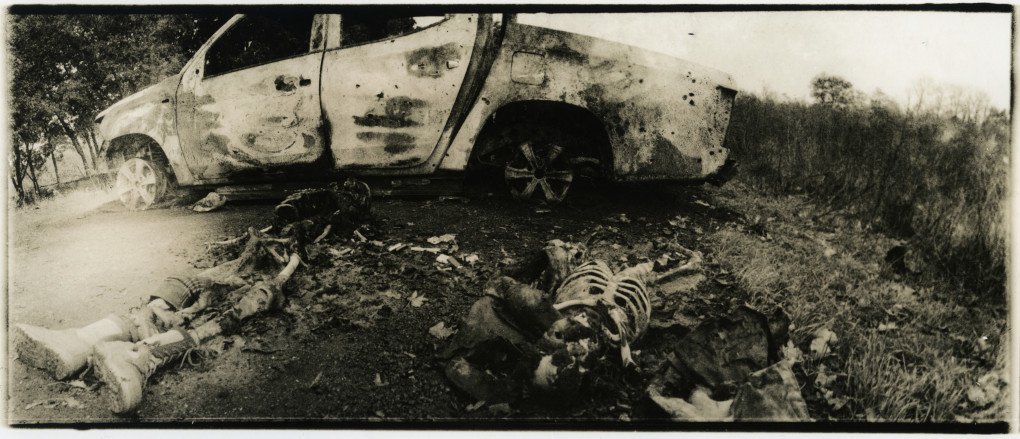

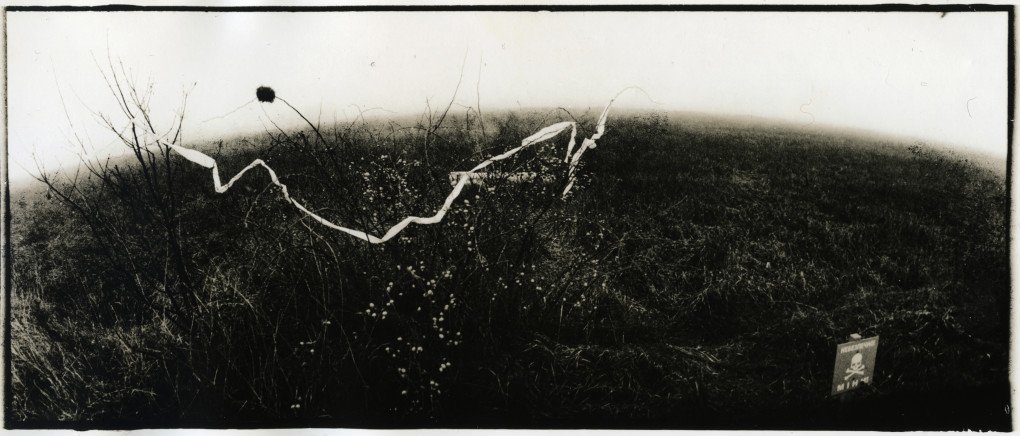

The war turned Vladyslav Krasnoshchok, a Kharkiv surgeon and underground artist, into one of Ukraine’s most provocative war photographers. His language is raw, and his images even more so—together they capture a truth that goes beyond what the eye sees.

DISCLAMER: The language in this article—and the photographs accompanying it—may disturb sensitive readers.

“In this house lives and works V. KRASN.”

“I always dreamed of being a war photographer. I’d look at war photos and think I could make that look beautiful. I became one today, but fuck, it wasn’t supposed to happen like this… You should never trust your dreams too much!”

The man speaking is Vladyslav Krasnoshchok—“Krasnyi” (lit. Red) to those who know him. He is Ukrainian, a maxillofacial surgeon at a Kharkiv clinic in eastern Ukraine, just 30 kilometers from the Russian border and roughly an hour’s drive from the city of Kupiansk, one of the most active frontlines of Russia’s war.

We bring you stories from the ground. Your support keeps our team in the field.

Kharkiv was once Ukraine’s capital in the early 20th century. It is where the Soviet nuclear bomb was invented. It is also where several generations of brilliant Ukrainian artists were killed by the Soviet secret police, NKVD, and later the KGB, from the 1930s until the collapse of the USSR. The city, full of students before the full-scale invasion, smells of knowledge, art, powder, and blood.

Krasnoshchok is one of Ukraine’s most talented documentary photographers, and one of its least conventional—meaning one of its most Ukrainian. His work has traveled worldwide and been featured in prestigious collections, including the Centre Pompidou in Paris. Since Russia launched its full-scale invasion, he has become, inevitably, a war photographer.

For this interview, I met him at home. His neighborhood is a cluster of small houses not far from central Kharkiv—the place where he grew up and where he returned after his parents’ deaths. On his front door, instead of a simple nameplate, a ceramic sign reads, as if announcing that a dead artist of national significance once lived there: “In this house lives and works V. KRASN.”

When I ring the intercom, a voice shouts: “Ah no, the military office again—fuck, not you! Go away!” I reach to ring again, but the door suddenly opens. In the small garden that surrounds the house stands Vladyslav Krasnoshchok, laughing. It’s already cold, but as a first reminder of his dialectic way of living, he’s wearing shorts with valenki .

Does Picasso know me?

At 45, Krasnoshchok is a member of the legendary Kharkiv School of Photography, founded in 1971 by Jury Rupin, Evgeny Pavlov, Oleg Maliovany, Gennadiy Tubalev, Oleksandr Suprun, Oleksandr Sitnichenko, Anatoliy Makiyenko, and the one best known today, Boris Mikhailov. Their practice, until the fall of the USSR, was to reject or distort everything the Soviet dictatorship produced as visual culture. A documentary series, made by the Ukrainian director Olha Tchernykh, and co-produced with the French-German broadcaster ARTE, depicts their history and features, among other, Krasnyi.

Krasnyi remembers his difficult beginnings. “I started with film,” he says. “I had a Zenit . I took some color photos—flowers, bullshit like that. Then I dreamed of buying a digital camera.” But even then, the results didn’t convince him. “I posted my photos online, and the comments were unanimous: ‘this is shit!’”

“But I started to fucking understand what was happening,” he continues, ecstatic, as if reliving this artistic revelation. “I kept trying and trying until I took fucking amazing photos! That’s when I met the guys from the Kharkiv School of Photography.”

He later created the group Shilo with Kharkiv photographer Serhii Lebedynskyi, who now directs the School. Most of its archives were moved to Germany in 2022 to avoid destruction as Russian forces approached the city.

Pushed by his new peers, Krasnyi returned to film. Like them, he began by photographing Kharkiv—sometimes coloring or collaging his prints—before drifting into painting: on his walls, on city walls, on canvases, pig legs, Petri dishes, scraps of leather.

“You see,” he tells me in his kitchen, which also serves as his darkroom, “I see my work like a tree. The trunk is photography. The branches are everything else: murals, paintings, collages, sculpture, linocuts. When I’ve done what I needed with a branch, I return to the trunk to grow another. I always come back to photography.”

His house-museum is full of his works. He mixes political events with his daily life in ways that are intentionally bawdy—a wall covered with a heavy dresser, family photos, painted phalluses, and breasts is what he calls “The Freud Wall.”

Everything is useful, for him, to resist what he lumps together under the term “religion”: the USSR, modern Ukrainian politics, advertising, the worship of artistic figures—or art itself—Trumpism, and more. When asked whether he knows Picasso or any other famous artists, he answers immediately: “And does he know me?”

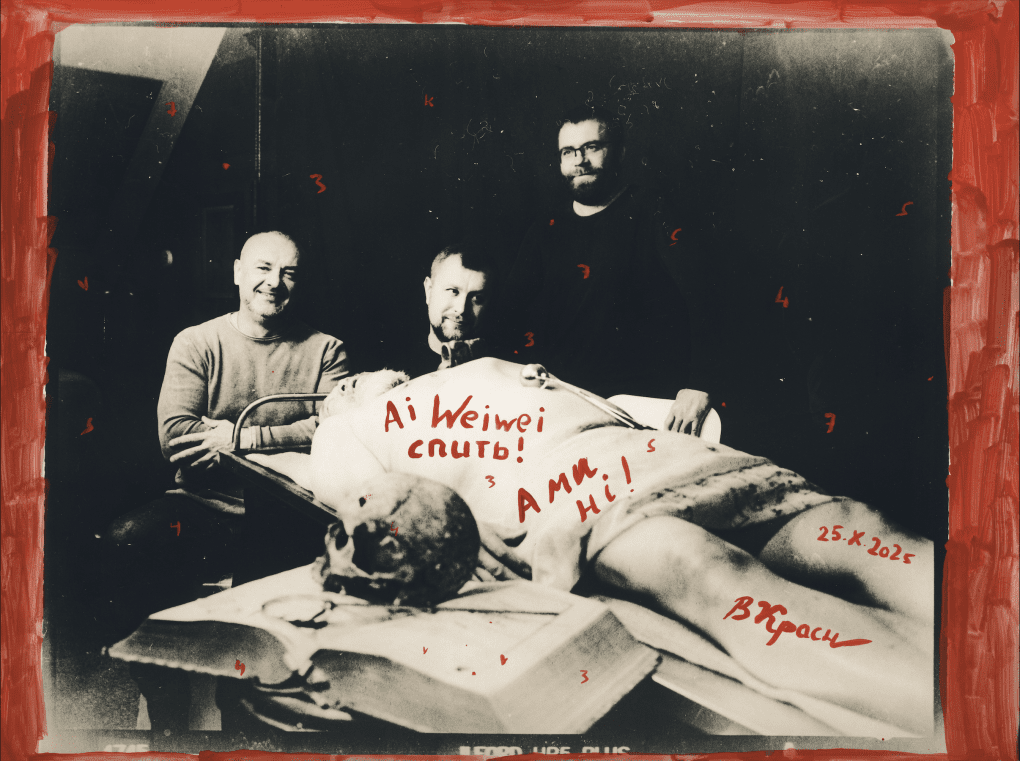

A friend of his—a forensic doctor and ambrotype photographer—once brought the famous Chinese artist Ai Weiwei to visit his house-museum. “He was shocked by everything I do,” Krasnoshchok says, half-ironic and half-serious. “He left saying, ‘Fuck… after seeing what Krasnyi has made, I need to start everything from scratch again.’”

His hyperbole—about himself and his work—is deliberate. It is a provocation, a way to force his audience to think harder, to adopt a skewed angle, to abandon passive viewing.

Beneath his rough manners and dockworker language, Krasnyi is the son of university professors—and a highly qualified surgeon. He says he chose his profession by eliminating every field he would never want to study, and what remained was surgery. The job acts on him like a trance. His obsession with creating hits hardest after he returns home, exhausted from a day in the operating room.

Creating work is a way to fight my own stress. It distracts me from the war. If I didn’t do it, I’d be in a deep depression.

Vladyslav Krasnoshchok

Ukrainian photographer

Time to operate and time to photograph

It isn’t an exaggeration to say that Russia’s war against Ukraine is the most filmed war in history. Beyond photojournalists, civilians and soldiers take photos with their phones. Many soldiers carry helmet-mounted GoPros that they keep running during assaults. Drones film the battlefield—and tens of thousands of times each month, they film death in real time. As major platforms relaxed moderation of violent content, the visual horrors of war became part of daily life.

Talking about war photography, Susan Sontag, the famous American writer and photography specialist, wrote, “We can’t imagine how dreadful, how terrifying war is; and how normal it becomes.”

To question this new sense of normality, we need a certain distance—the kind only thinkers and artists can give us. And Krasnyi defines himself first and foremost as an artist with a totally different documentary approach.

War, for an artist, is such a rare event—you have to take advantage of it. Above all, you must do what you know how to do in moments like this. I’m a surgeon and a photographer. I know how to treat people and how to photograph. So that’s what I do!

Vladyslav Krasnoshchok

Ukrainian photographer

“I don’t know how to fight,” he says. “But I can show what happens in this period. It felt like a beautiful combination: I treat people—I have many patients, civilians and soldiers—and in my free time, I eat, I work out… and I photograph the war.”

His provocations hide a deeper artistic lineage.

The photographic image … cannot be simply a transparency of something that happened. It is always the image that someone chose; to photograph is to frame, and to frame is to exclude.

Susan Sontag

American writer

Krasnoshchok’s view aligns with Susan Sontag’s—“a photograph isn’t the negative, but the printed image,” he says—and pushes further. What is excluded becomes the viewpoint. “There is no failed photograph,” he says. “Every image must be brought to a state where it works for the viewer. An image works when its final form is found. That requires manipulating it—sometimes starting with a failed shot.”

As he says himself, his documentary approach mirrors that of a novelist facing a blank page, studying the world to fill the mind with new images, a richer imagination.

Imagination is not the ability to form images of reality; it is the ability to form images that surpass reality, that sing reality.

Gaston Bachelard

French philologist

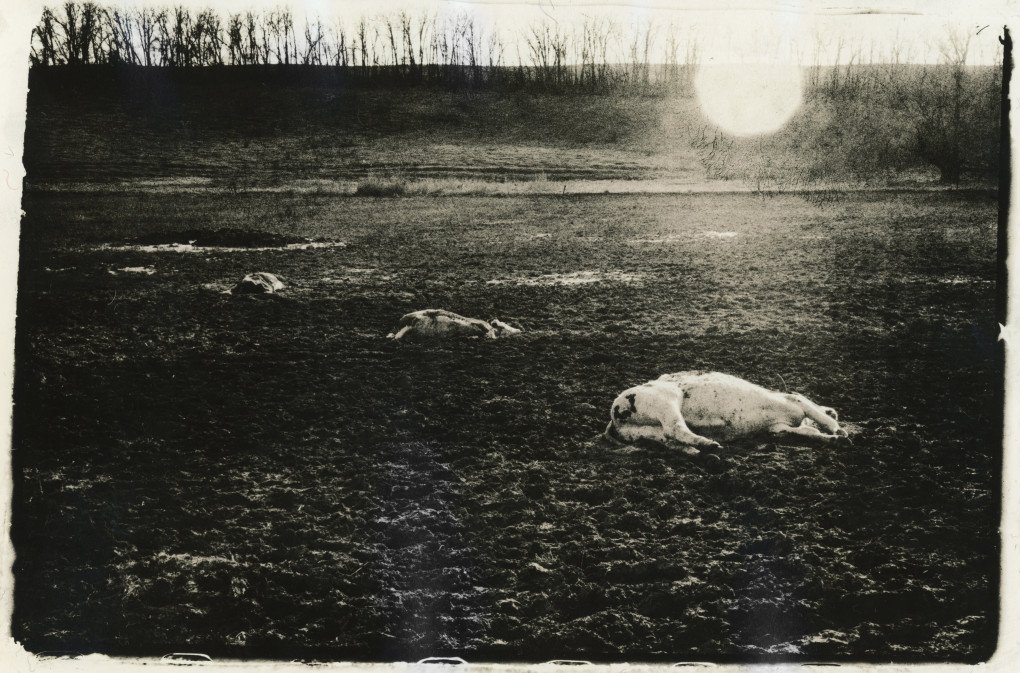

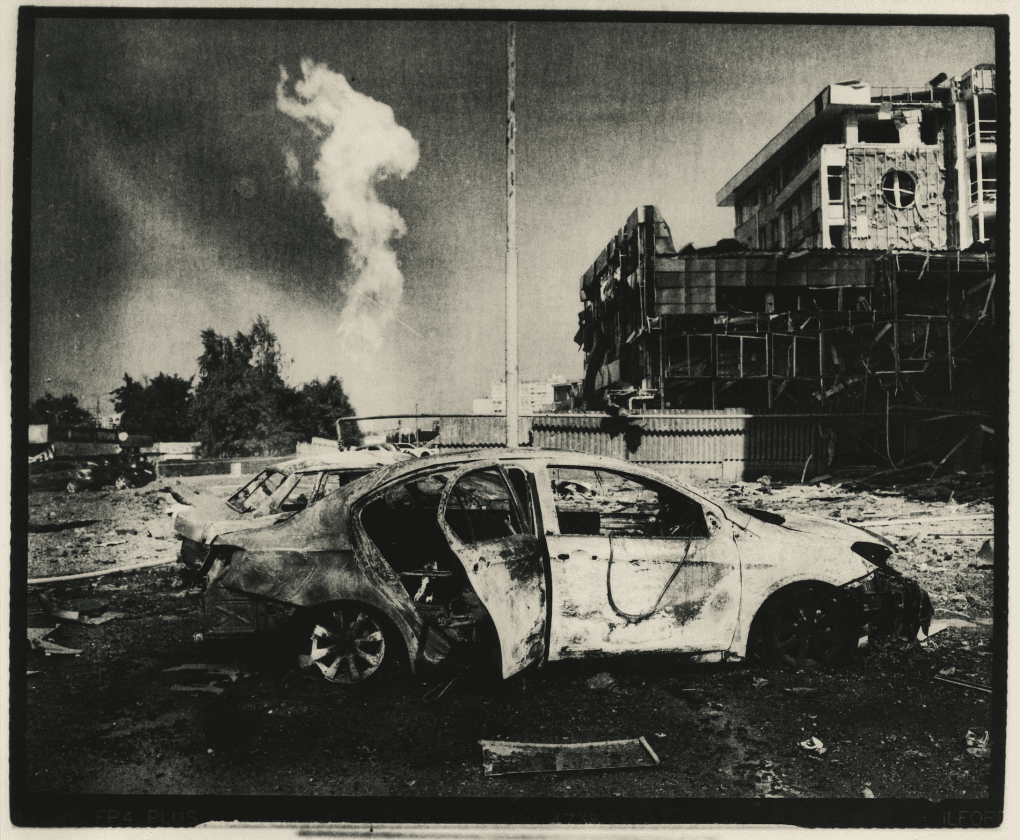

And you see this in Krasnoshchok’s photographs—brutal yet composed, dirty yet labored over for hours in the darkroom. They criticize the myth of war photography—in other words, they praise and distort the myth at the same time. Sometimes, you can feel that they were made during the First or Second World War. Modernity often appears only through details: a drone, a modern artillery piece, missile debris, or a photographer friend pissing on an abandoned Russian tank.

“There are things I can’t show, and things not everyone is ready to see”

With his four to six analog cameras around his neck, Krasnoshchok’s process may look playful, but like any war photographer, he takes real risks.

In 2024, while photographing D-30 artillery crews with Ukrainian photographer Olha Kovalova—an ambassador of the Ukrainian Association of Professional Photographers—their shelter took a direct hit. A shell exploded, and a piece of shrapnel entered through the ventilation pipe. Kovaleva was sitting right in front of it.

“The katsaps fired eight to ten times at us. When the shell hit us directly, a shrapnel piece came through the ventilation pipe, and Olha was sitting opposite it. She was wounded in the shoulder.

Vladyslav Krasnoshchok

Ukrainian photographer

Because her life wasn’t in urgent danger, it took them an entire day to find a hospital that would treat her. She was eventually admitted to Kharkiv. Kovalova still has partial paralysis in her arm.

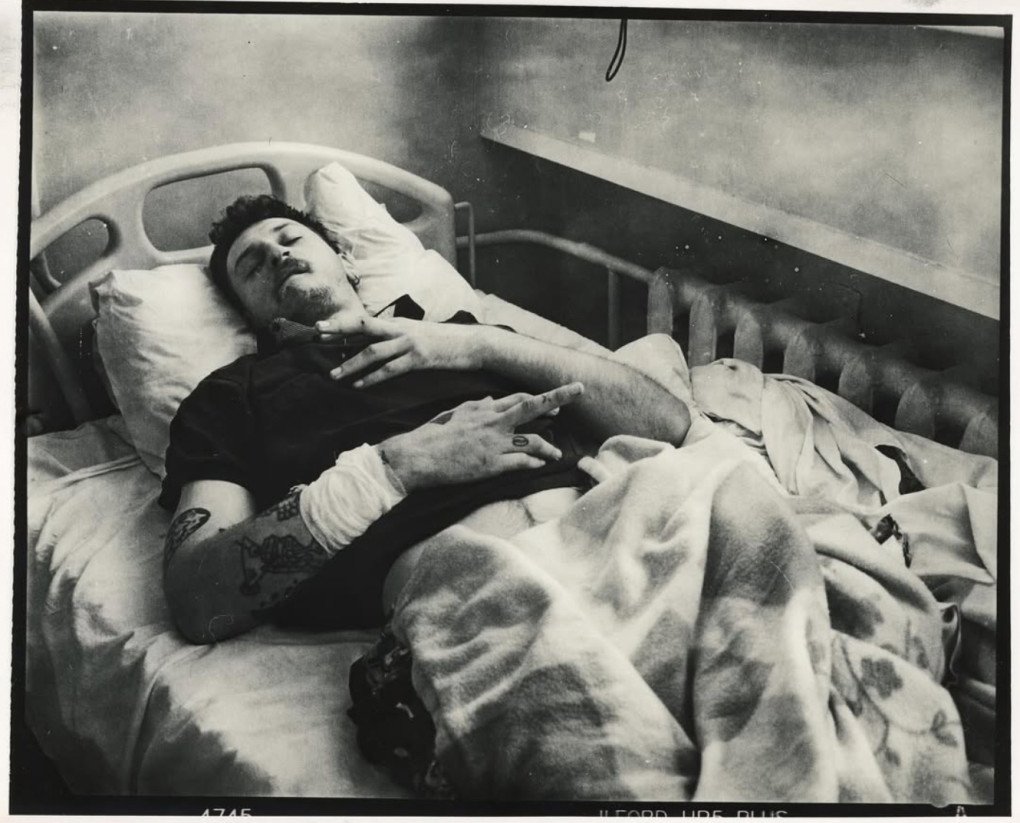

Another of Krasnyi’s friends had less luck. A Russian FPV drone struck the car of Ukrainian photographer Hryhorii Ivanchenko and French photojournalist Anthony Lallikan. Lallikan was killed instantly. Ivanchenko survived but lost a leg. Visiting him in the hospital, Krasnoshchok took a photo that perfectly captures this Ukrainian resilience and dark humor that continue to astonish the world.

Krasnyi’s work is not random. It follows themes. “It’s impossible to photograph everything in war,” he says. He has a list of subjects he wants to complete before the war ends: a helicopter brigade, a Russian prisonners camp, and other themes he will only publish after the fighting stops, so as not to endanger the people he photographs.

“As social research, some things are very important,” he says. “But there are things I can’t show, and things not everyone is ready to see.”

He is especially interested in the new role of combat helicopters in Ukraine’s defense—shooting down Shaheds with a soldier positioned at the open door holding a heavy machine gun.

Now what I want is to fly with the helicopters and film them shooting down Shaheds.

Vladyslav Krasnoshchok

Ukrainian photographer

In the meantime, he is preparing the release of his next book, Documentation of the war, to be printed by a New York publisher before the end of the year. He regularly publishes books — with a level of care that contrasts sharply with the brutality of his photographs — so his work can be recognized and preserved somewhere safe, far from the bombing.

The war, in Ukraine and for millions of people around the world, is a 24/7 reality, and today — and for the generations to come — amid the constant noise of image production, artists like Vladyslav Krasnoshchok are the ones who make us pause and reflect.

An artist is a philosopher and a preacher. He brings his philosophy into the world.

Vladyslav Krasnoshchok

Ukrainian photographer

-457ad7ae19a951ebdca94e9b6bf6309d.png)

-24deccd511006ba79cfc4d798c6c2ef5.jpeg)

-60190095464c40ccbc261d2114a1fe68.png)