- Category

- War in Ukraine

Is Europe Ready for Russia’s Shahed Swarms? Mapping Air-Defense Gaps and Fixes

“If swarms of Shaheds are heading toward France, Sweden, the Baltic States—what do we do?” As Russia’s drones batter Ukraine’s skies, experts warn that Europe’s air defenses may be unprepared for such mass drone and missile attacks.

Speaking on Le Collimateur on July 11, 2025, Belgian air and naval warfare specialist Joseph Henrotin warned his interviewer: “If we have swarms of Shaheds heading towards France, Sweden, the Baltic States—what do we do? We have a series of missiles, but our stockpiles will be depleted very quickly. It’s not with the SAMP/T that we’re going to solve the problem.”

On August 20, 2025, about 100 km from Warsaw and 40 km from a NATO air base meant to protect the airspace, a Russian drone struck a civilian area in Poland.

Osiny, lubelszczyzna, ok. 100 km od granicy z Ukrainą. Policja odnalazła nadpalone, metalowe i plastikowe szczątki. https://t.co/tdwN6vQ0cq pic.twitter.com/zz3D7Wmi2V

— 1 Star (@PawelSokala) August 20, 2025

According to Defense Express, the absence of interception can be related to the absence of a complete network of ground-based radar intended to detect low-altitude threats, “as this would require positioning stations every 30–50 kilometers”. And what applies to Poland appears to apply to other European countries as well.

After a series of similar incidents in Lithuania and Romania, we see how Russia’s aerial threat in Europe is growing.

A new threat

Since September 2022, Russia has been investing huge ressources in the mass production of low-cost attack drones, while prioritizing the production and modernization of ballistic missiles. This has resulted in airstrikes that underpin Russia’s policy of terror against Ukrainian civilians and help sustain its role in the balance of deterrence. This new strategy, driven by mass drone attacks—dubbed the “Shahed Blitz” by The Guardian—has become a defining feature of its air campaign.

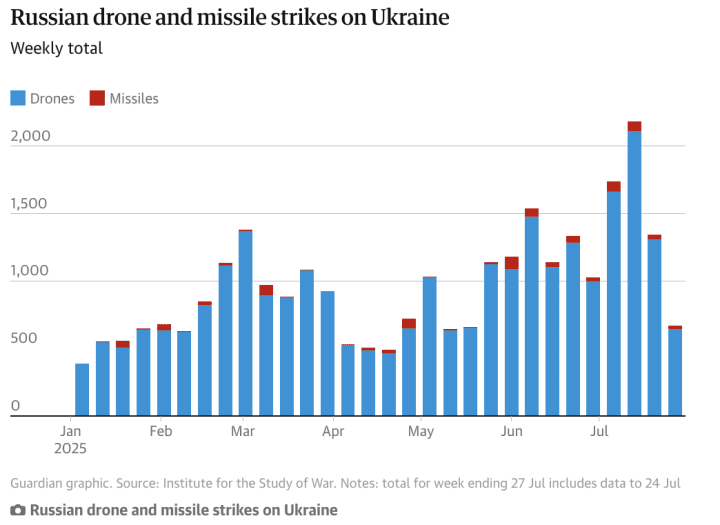

Indeed, Ukrainian cities are regularly subjected to multi-layered attacks involving glide bombs, drones, and cruise or ballistic missiles. In July 2025 alone, Russia attacked Ukraine with 6,297 long-range drones, 16 times more than during the same month in 2024. Added to this were 198 missiles of all types and over 5,100 glide bombs. That same month, the capital, Kyiv, endured nearly 80 hours of air raid alerts, slowing the economy and forcing thousands into sleepless nights and bomb-shelters.

Former NATO Supreme Allied Commander Europe, Philippe Breedlove, put it bluntly: “You see what has happened in big cities in Ukraine. This also would happen in some of the big cities of Europe.”

Experts across the continent have sounded the alarm, calling on European states to overhaul their military strategies, rearm at scale, and knit their defenses into a common architecture capable of facing down the Russian threat. But the path ahead is difficult.

There is a mismatch between the demand for air and missile defense and what the Allies can supply.

International Center for Defense and Security (ISDC)

Lessons from Ukraine

Ukraine today fields one of the most sophisticated—if improvised—air defense shields in the world. Built layer by layer since the first Russian missile barrages of 2022, it combines old Soviet hardware with cutting-edge Western systems, and increasingly, cheap drones fighting other drones.

At the top sit US-made Patriot batteries (PAC-3 version) and Franco-Italian SAMP/T launchers, capable of knocking down ballistic missiles such as Russia’s Iskander or even the much-vaunted Kinzhal. These systems, however, are scarce and prohibitively expensive: a single interceptor costs several million dollars. The Americans, having initially refused to authorize their delivery, citing cost and the risk of escalation with Russia, allowed the donation and sale of Patriots and their munitions starting in December 2022.

Further down, Ukraine relies on a patchwork of legacy Soviet S-300s and Buk launchers alongside US Patriots in their older PAC-2 version. They can cover large swathes of territory against cruise missiles and aircraft, but Soviet-era missiles are running out, and replacements are hard to find.

The backbone of the defense comes from medium-range Western donations: Germany’s IRIS-T, Norway’s NASAMS, and French Crotales. They are accurate and mobile, but each shot still costs hundreds of thousands of euros, a heavy burden when hundreds of Shahed drones descend in a single night.

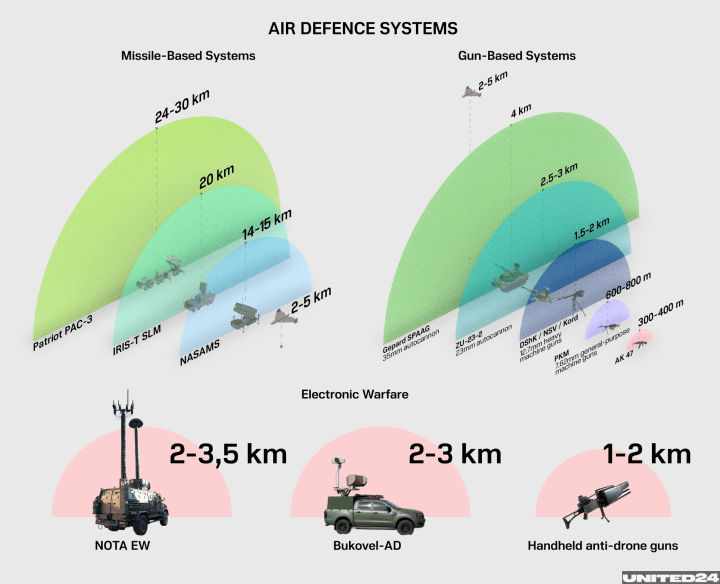

Close to the ground, the defense becomes more economical. German Gepards fire 35-mm shells costing a fraction of a missile, while shoulder-fired Stingers provide quick reaction against drones or helicopters. In the last two years, Ukraine has developed an AI-powered missile turrets, the Sky Sentinel, has also pioneered eletronic jamming as a new layer of defense and has launch the “drone-on-drone” combat system, with cheap FPV drones intercepting Russian Shaheds mid-flight. A popular initiative, Shahedoriz, was even launched by blogger Sternenko to supply the Ukrainian army with Shahed-killer drones.

The European countries, which almost unanimously provided military aid to Ukraine, quickly realized that they had lessons to learn from Russia's war.

Belgian air and naval warfare specialist Joseph Henrotin agreed to speak with UNITED24 Media about the lessons Ukraine is given Europe on air defense.

The first lesson is that a ‘multi-layered’ defense is necessary: it is dangerous to fire the few available Patriot missiles to counter swarms of Shaheds—you end up wasting the few hammers you have on flies.

Joseph Henrotin

Belgian air and naval warfare specialist

“We need systems adapted to each threat”, says Henrotin, “That means diversifying the types of missiles and guns—anti-aircraft artillery being a category largely abandoned in Europe—as well as the modes of action.”

It’s also important to note that no air defense system can intercept every missile. Even Israel’s Iron Dome—considered one of the most advanced in the world—failed to stop all of the missiles Iran launched at it in April 2024. « Europe will not be able—will never be able—to put any kind of umbrella over all its countries, all its cities » said Dr. Ulrike Franke, according to Forces News. Russia exploits these “holes”, launching combined attacks on Ukraine that force air defense operators to choose between protecting critical infrastructure and risking missile fragments striking civilian buildings.

“The second lesson is that nothing replaces mass,” Henrotin says. “Ukraine historically had the strongest air defense in Europe, which allowed it to cover its troops and protect cities as much as possible for an entire year. If, like many European states, it had lacked this mass, the counteroffensives of 2022 would not have been possible.”

The Ukraine’s air defense system is thus constantly affected by requests and delays in the delivery of new systems and the replenishment of missile stocks—particularly for the upper layer, the most expensive and complex to keep operational. Russia, whose stockpiles appear much emptier compared to the beginning of the invasion, is also operating on a tight flow, striking Ukraine with its freshly produced missiles. Ukraine must be constantly supplied with air defense systems to prevent Russia from rebuilding its stockpiles and launching even larger attacks.

In 2023 and beyond, the shortage of air defenses meant that protection had to be stripped from the troops in order to protect the cities. This was one of the reasons for the failure of the spring 2023 counteroffensive. Stockpiling logic must therefore take precedence over just-in-time supply.

Joseph Henrotin

Belgian air and naval warfare specialist

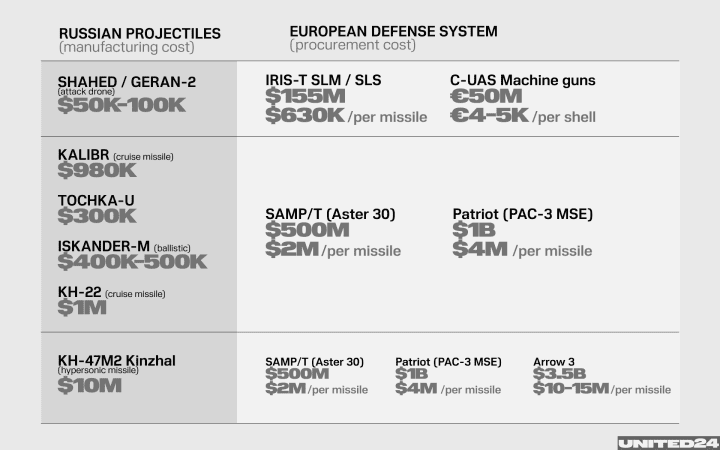

There is also a crucial dimension to consider in the attrition war Russia has launched against the West: the trade-off between the cost of defense, the value of what is being protected, and the cost of the threat itself. While a Shahed drone costs Russia only $50,000–100,000 to produce, shooting it down with an IRIS-T interceptor drains European stockpiles of a missile worth roughly €630,000. Even if neutralized by a 35 mm cannon shell — at about €4,000–5,000 apiece — the balance still tilts heavily toward the attacker.

The disparity grows sharper with cruise and ballistic missiles. A Kalibr, priced at just under $1 million, may be intercepted by an Aster-30 missile costing $2 million — a net disadvantage of roughly $1 million per shot. If the defender uses a Patriot PAC-3 MSE, the imbalance doubles: $980,000 versus $4 million.

For short-range ballistic missiles like the Tochka-U (around $300,000), or the more modern Iskander-M ($400,000–500,000), Ukraine again spends multiples more: $2–4 million per interceptor, widening the gap by several million dollars each time.

The equation peaks with hypersonics. A Kinzhal, costing about $10 million, forces defenders to rely on systems like Arrow-3, whose interceptors alone run between $10–15 million. Here, the economics finally tilt closer to parity, though only because both sides are spending astronomical sums.

In essence, the battlefield math favors Moscow: every missile it fires is cheaper than the missile needed to stop it, a dynamic that puts pressure on Europe to expand cheaper alternatives — electronic warfare, drone-on-drone defenses, and rapid-fire guns — rather than burning through billion-dollar systems designed for a different era.

The “virtue of civil defense”

One of Ukraine’s most notable advantages during Russia’s full-scale invasion has been the active involvement of civil society in the war effort—constructing and equipping shelters, delivering first-aid medical assistance, and directly investing in innovative solutions for the armed forces. What Joseph Henrotin has described to us as the “virtue of civil defense”:

During the Cold War, very few countries had a real culture of civil defense—after all, in a nuclear war, survival depends on more than just the first days. Some states will have to learn all of this from scratch.

Joseph Henrotin

Belgian air and naval warfare specialist

The easing of bureaucratic constraints launched by Ukraine with programs such as Brave-1 is also central to supporting innovation. This seems to be one of the weak points of European armies.

“We must shorten innovation cycles, which means lowering our standards for weapon qualification: speed of deployment matters!” continues Henrotin.

Electronic warfare

The final lesson is the importance of electronic warfare. Today, it is mostly used for intelligence, but far less for offensive actions such as jamming or spoofing. Here too, a cultural shift is necessary. Missile defense can mean destroying enemy stockpiles before launch, but also electronic warfare.

Joseph Henrotin

Belgian air and naval warfare specialist

Ukraine has integrated electronic warfare as a full-fledged layer in its air defense architecture. Shahed drones are first jammed by various, more or less mobile systems, forcing them to crash as they approach certain vital infrastructures. At the front, brigades have all integrated a division specialized in electronic warfare—something rare in NATO countries.

Is Europe prepared?

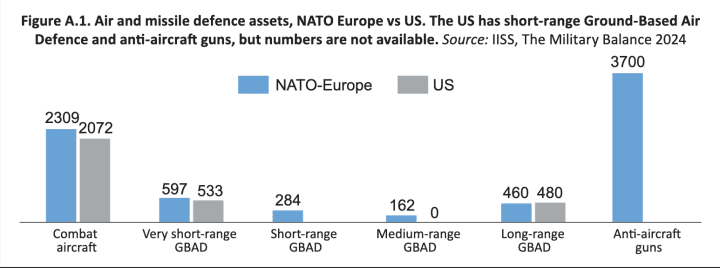

As one of the main integrated defense systems among European countries, NATO admitted to having only 5% of the required air defense capacity to protect its eastern flank. Most European states have limited systems designed for sporadic threats, not daily saturation, as seen in Ukraine.

Taken as a whole, the European members of NATO actually have greater air defense capabilities than the United States across most layers. It is therefore less a question of quantity or quality than of cooperation and system integration. It is obviously not useful for each country to possess the entire arsenal necessary to protect itself from a Russian attack; European countries need to design the architecture according to Europe’s overall geography, its industrial and human networks, and the types of threats one country or another may face. It is also essential that European countries pursue a common policy of pooling their purchases of systems and munitions, along with a coordinated approach to their deployment.

Full integration of Europe’s various air defense systems could help compensate for the shortfall by creating a dense mesh of sensors and interceptors across the continent. But attempts to update NATO’s command and control infrastructure for air defense have never gotten off the ground.

Jack Watling (for the Financial Times)

Senior Research Fellow for Land Warfare at the Royal United Services Institute (UK)

The European Sky Shield Initiative (ESSI)

Europe is actively trying to prepare for the new scenario of a massive Russian-style air attack, notably through a series of more or less promising initiatives, including the European Sky Shield Initiative (ESSI).

Launched in October 2022 by Germany, the ESSI is both a sign of renewed awareness and a marker of a certain disunity among European countries on this issue. The initiative—not linked to the European Union—today brings together 23 European countries: Albania, Germany, Austria, Belgium, Bulgaria, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, the UK, Greece, Latvia, Lithuania, Norway, the Netherlands, Portugal, Romania, Slovakia, Slovenia, Sweden, Switzerland, Czechia, Türkiye and Hungary.

It aims to establish a ground-based, integrated, multi-layered air and missile defense across Europe. This architecture, strongly inspired by Israel’s Iron Dome system, will be based on a variety of systems designed to cover all layers: Skyranger 30, IRIS-T SLM, Patriot PAC-3 MSE, and Arrow 3, and will be integrated into NATO’s already existing structure. The aim of the initiative is “to strengthen the European pillar within NATO’s collective air defense,” announced Germany’s Ministry of Defense.

But the initiative has not received support from all European countries. France, first and foremost, criticized ESSI for being too closely tied to the purchase of foreign equipment, notably American and Israeli, without even integrating the SAMP/T system, which is of European production. Spain and Italy, which also rely on the SAMP/T system, didn’t join ESSI either. Poland, whose Prime Minister Donald Tusk initially expressed interest in joining ESSI, ultimately did not sign on. President Andrzej Duda—who, as head of state, is also the supreme commander of the armed forces—criticized the initiative as giving Germany an overly dominant leadership role.

In the end, what seemed to be an initiative intended to contribute to strengthening NATO in the matter of European defense could instead lead to a political and technical fragmentation of air defense integration in Europe. This disunity could be exploited by Russia, which—without even starting a conflict with a European country—would reinforce its position of deterrence toward Europe.

Toward a join european early warning system?

To counter this idea and make the Franco-German partnership a driver of unity rather than division, France and Germany announced, on August 29 in Toulon, plans to expand Europe’s early-warning systems with JEWEL, a new ground-based radar network meant to complement the ODIN’S EYE space project. According to Zone Militaire, by combining space-based and terrestrial radars, Paris and Berlin aim to strengthen Europe’s ability to detect ballistic and hypersonic threats without relying solely on US assets.

Europe’s new air defense architecture— not if but when

Since Russia launched its full-scale invasion of Ukraine, it has become clear that Moscow’s ambitions go beyond Ukraine’s borders. Ukraine has become Europe’s air-defense umbrella. By integrating Western systems into its military architecture and adapting in real time to new threats, Ukraine now has an advantage, still unmatched by European states—individually or together.

But at the same time, Russia is ramping up production, with an estimated 2,500 medium-range missiles planned for 2025. These weapons threaten not only Ukraine but all of Europe.

The question is thus not if Europe can scale up its defense, but when. Without accelerated investment, industrial mobilization, and integration, Europe risks facing a Shahed swarm unprepared. This is a call for political will to match technological capability, and a reminder of the need to support Ukraine, which is defending Europe from airstrikes and preventing Russia from building up its stockpiles.

-24deccd511006ba79cfc4d798c6c2ef5.jpeg)

-347244f3d277553dbd8929da636a6354.jpg)

-f88628fa403b11af0b72ec7b062ce954.jpeg)

-554f0711f15a880af68b2550a739eee4.jpg)