- Category

- War in Ukraine

Russia’s New Deadly Rubikon Unit Escalates Drone War Against Ukrainian Civilians

A Russian precision drone strike turned a Ukrainian coal train into a graveyard—part of a new phase in drone warfare suspected to be led by the Kremlin’s Rubikon military unit, testing next-gen drones on civilian targets further away from the front.

Content warning: Contains graphic imagery of human remains.

The train came to a violent stop in a wildflower field beside the Bilozerska coal mine, deep in eastern Ukraine’s Donetsk region—purple blooms stretching as far as the eye could see, thistles, and the occasional lonely sunflower. Scattered across the grass lie shrapnel, bent pieces of metal, and spilled coal.

Three exhausted rescue workers lay down their hoses after hours of battling the flames. They begin to inspect the wreckage. The train itself—a once-colorful locomotive from Ukrzaliznytsia, Ukraine’s state-owned railway company—is now completely gutted.

A Russian drone strike killed the engineer and his assistant instantly; now the cab is completely burned out.

Almost nothing is recognizable. Ashes from human remains mingle with the charred remnants of melted seats; rusted iron twists in all directions. Only the steering handle has kept its original shape.

The machinist and his assistant had come to pick up coal from the Bilhorivka coal mine, just outside Dobropillia—a town about 20 kilometers (13 miles) from the frontline. Around 2 a.m., their train was struck by a Russian drone. It was the fifth consecutive day of Russia’s FPV drone attacks on Dobropillia and its surroundings—a sustained assault targeting civilian infrastructure and logistical routes with remote-controlled precision.

"There's really almost nothing left," says one of the firefighters as he unzips the body bag. It's hard to grasp that the pile of charred remains behind the controls—white, splintered bones and yellowish, unidentifiable matter—was just a few hours ago a human being, with thoughts, feelings, and opinions. "Look there," the firefighter says, pointing to something dangling on the side of the train. "A foot."

His colleague lifts it—the most obvious part to place in the body bag—then begins gathering the remaining lumps of tissue and bone. At the second seat, where the machinist must have sat, the process is repeated. They find what appears to be a torso and, with some quiet doubt, add a few more scattered fragments—some bone, some flesh—to the bag.

The loss leaves behind not only grief and paranoia among colleagues and loved ones, but also confirms a grim suspicion that has been haunting many: FPV warfare is evolving fast—and there’s no turning back.

FPV drones now reach farther than ever

“We’ve never seen anything like this,” says Oleksandr, 31, a rescue worker with Ukraine’s State Emergency Service (DSNS). “There were explosions every 20 or 30 minutes—forty drones hit the city,” he recalls about the day of the attack. “Even the boys who used to work in Avdiivka and Pokrovsk don’t remember anything like it.” They found pieces of the suspected drone that killed the mineworkers. “It looked like pieces from a shahed”, Oleksandr’s colleague Dmytro, 27, says. “There’s no way a [regular] FPV could have caused so much damage.”

Russian drone innovation is taking a sharp and unexpected turn near Dobropillia. By doubling the battery life of basic FPV drones, Russia has demonstrated the ability to coordinate large-scale strikes deep behind the frontlines—targeting logistics hubs and severing supply routes with striking precision.

Civilian sites in and around Dobropillia were hit with an intensity not seen before. On the first day alone, a vape shop, a car wash, a car dealership, several private vehicles, and a branch of Nova Poshta—Ukraine’s largest private delivery and logistics company—were all struck. The T-05-14 road from Dobropillia to Kramatorsk—despite Ukraine’s efforts to protect it with nets—was littered with burned-out vehicles within days.

What’s new isn’t the targets—but the method. These attacks were carried out by small FPV drones operating 17 kilometers (10 miles) behind the front line—the same distance, for comparison, as from Chasiv Yar to Kramatorsk. What also cannot be ignored is the moral degradation at play. Most Russian FPV drone pilots see crystal-clear footage of their targets—like the three elderly people who bled to death in their car in Rodynske, or the toddler killed in his crib in Kherson region—and strike anyway.

“We tried to put out the fire with water, but it was already too late,” says Taia, 68, a security guard at the second-hand car dealership Donbas Avto. When she heard about the attack, she ran straight to her workplace. “My son is in the army. He joked, ‘I didn’t know you were a patriot—it was your day off!’”

She herself lives nearby. “My apartment is here,” she says. “Some people left, but when they ran out of money, they came back. My pension is just 3,000 hryvnias ($72)—I could never afford to rent a place in western Ukraine. And if I leave, who can guarantee a drone won’t hit me somewhere else? Now I worry about my son, and he worries about me.”

Rumours spread fast—of FPV drones peeking through windows and attacking at random, far from the front line. Not every drone is FPV, but for most civilians, drone warfare evolves too quickly to keep up. The psychological impact is enormous—who knows how far they can reach? Take Ocheretyne, a town in Donetsk region, for instance, where a drone struck some 40 kilometers from the nearest front-line position.

Despite Russia’s rapid progress with FPV drones, it is more plausible these attacks are carried out by a different class of weapon Russia is now experimenting with. Ukrainian soldiers refer to it as “Molniya”—a nickname for a new type of small loitering drone. These drones are fixed-wing, crude but effective. They carry a warhead, up to 4 kg of explosives. Since late 2023, they’ve been used to strike targets 15–20 kilometers behind the line. They’re cheap, hard to jam, and as of recently, increasingly common.

Reports from the battlefield indicate the appearance of a new drone, a compact kamikaze model that resembles a smaller version of the Iranian Shahed, but is built for tactical precision strikes. These drones are already in use and are operated like FPV drones, providing high maneuverability and real-time targeting.

There are two variants, a reconnaissance version without explosives and a strike version capable of carrying up to 15kg of explosives. This development likely reflects a response to Ukraine’s improving air defenses and underscores the ongoing technological arms race in drone warfare.

Russia’s UAV assassination squad

Rubikon (or Rubicon)—a relatively new and shadowy Russian drone unit that emerged in late 2024—is most likely responsible for the wave of drone attacks in Dobropillia, say Ukrainian soldiers stationed in the area.

Russia has created a “Rubicon” military unit that actively hunts our drone operators.

Deputy Prime Minister for Innovation, Education, Science and Technology Development. Minister of Digital Transformation of Ukraine

The name “Rubikon” refers to a decisive point of no return. Known for its advanced use of FPV drones, the unit is part of an elite formation within the Russian military or special operations forces, tasked with testing next-generation drone tactics.

"To my best guess, they have around 50 positions," says Max, a Ukrainian drone pilot fighting in the Donetsk region who asked to remain anonymous. In his free time, Max has been closely tracking Rubikon. Research suggests the group was previously active near Kursk, but their crews have partly relocated to the areas near Pokrovsk. “They had training in Kursk, and now they’re experimenting here,” says Max.

Rubikon is responsible for strikes along key supply routes from Velyka Novosilka to Chasiv Yar, according to civilian Serhii “Flash” Beskrestnov, Ukrainian military expert. They deploy suicide drones that operate on a range of frequencies—including 3–4 GHz for video transmission and 2.1–2.7 GHz for control signals—to evade Ukrainian jamming efforts. To mask its involvement, the group often labels its drones under existing aliases such as GLADIATOR, SUDNY_DEN, TT, or ACTA NON VERBA in on-screen display feeds.

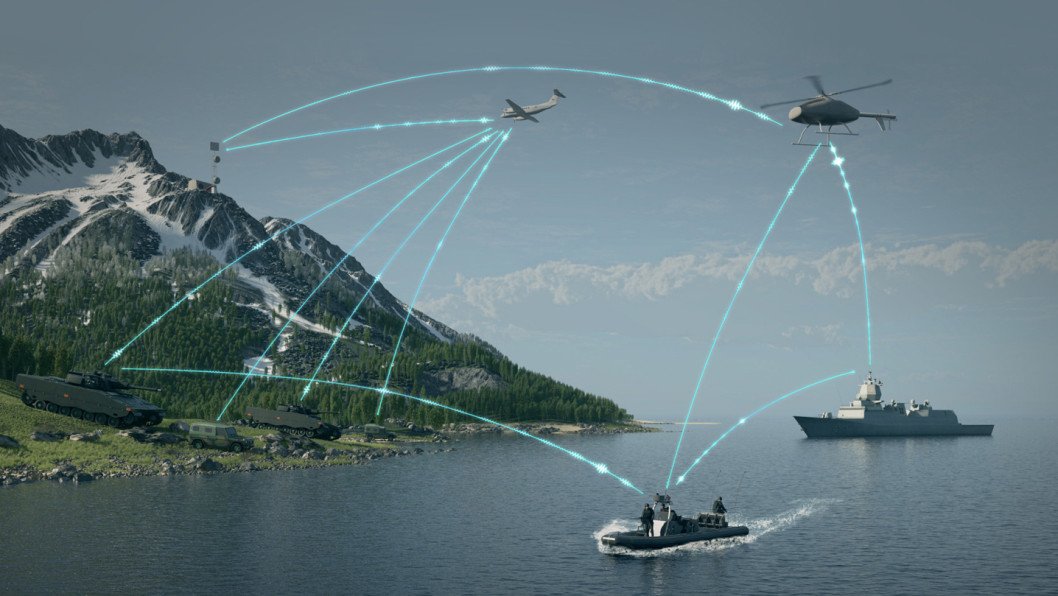

Beskrestnov also believes Rubikon coordinates closely with frontline reconnaissance units—part of a broader trend toward a centralized and increasingly professionalized Russian drone warfare operation. Rubikon has its own center for the development of unmanned systems and robotic ground complexes, as well as a training facility, analytics division, and dedicated combat units. The group operates across the full spectrum of UAVs, from Lancets and anti-aircraft drones to long-range FPV systems.

“They have an extremely strict selection process—only the best make it in,” says Max. “It’s an SSO drone center group. They get the best funding, the best equipment. Russia even sends resupply crews on military bikes—they’re too valuable to risk exposing.

Whenever a civilian is hit in a drone strike in Dobropillia and its surroundings, it’s most likely Rubikon, says Max. His assessment isn’t based on just guesswork: Rubikon doesn’t even try to hide its war crimes. “They regularly publish compilations of their drone strikes—including attacks on civilian targets,” he says.

In one instance, Ukrainian soldiers intercepted footage of a Russian FPV drone striking a civilian vehicle on the road to Sloviansk, approximately 18 kilometers (11 miles) from the frontline.

Max shows us the video, which was published on a Sloviansk media channel.

It was clearly not a military target. Just before impact, a woman—unarmed and dressed in civilian clothing—jumps from the vehicle. She was later confirmed dead. At the time, Russia’s Rubikon unit was the only unit that could do such a deep FPV strike.

Max

Ukrainian drone pilot

“Russian drones look like shit—but they work”

Just like regular Russian units, they use the Shtora electronic jamming system—a term circulating among soldiers to describe a technique that renders FPV footage unusable, as if pulling an electronic curtain in front of the camera.

“Ukraine could benefit from systems like this, but they’re not produced—because there’s no money in it,” says Max. “That’s the problem with private commercial companies dominating the market. The prices are insane. Russia—horrible as they are—cares about what works, not what sells.”

That’s just the tip of the iceberg when it comes to the problems Ukraine’s drone pilots experience. “There are a hundred companies, and it screws everyone,” says Max. “They’ll have amazing motors, then cheap out on the circuit boards and produce something completely useless. Russia has standardized production and consistently high-quality materials. Their drones look like shit—but they work.”

The pieces Oleksandr found could well belong to one of the so-called 'mini-Shaheds'—or more accurately, large FPV drones, according to Max. “Rubikon already operates with Molniyas and Lancets,” he says, “so there’s a high chance this was them testing something new.” If that’s the case, the strike near Dobropillia doesn’t mark a new target—Ukrzaliznytsia trains have been hit before—but a new method, greater range, and a troubling ease with which it was carried out.

-7d95c57e54dbfdfc91a3588f8f066e82.jpg)

-347244f3d277553dbd8929da636a6354.jpg)

-f88628fa403b11af0b72ec7b062ce954.jpeg)

-554f0711f15a880af68b2550a739eee4.jpg)