- Category

- World

Russia’s Criminal Army Strikes Europe From Within in a Wave of Attacks

Why waste elite spies when petty criminals will do? A new study exposes how Moscow is outsourcing sabotage and assassinations across Europe to gangs and convicts.

Russia has conducted or attempted 110 attacks on European soil since 2022—many not by spies but by criminals. With its operatives expelled, Moscow now turns to prisons, gangs, and vulnerable communities to carry out sabotage, arson, and even targeted killings to destabilise the continent.

A newly published joint study, “Russia’s Crime Terror Nexus,” by the International Centre for Counter-Terrorism (ICCT) and GLOBSEC shows—crime is central to Moscow’s foreign policy.

Russia is turning Europe’s underworld into a battlefield. Criminal recruits are no longer acting on their own—they are being weaponised as tools of state policy.

Dr. Kacper Rękawek

Lead author of Russia’s Crime Terror Nexus

UNITED24 Media spoke with Dominika Hajdu, editor and co-author of the report, who stressed that the West should draw hard lessons from Ukraine’s experience to dismantle Russia’s entire ecosystem of hybrid operations. “EU countries remain too slow, reactive, and cautious in responding to hybrid warfare, even as Russia grows more aggressive. If this does not change, we will lose”, Hajdu warns.

An old Soviet proverb reflects this deeply ingrained Russian perspective on law and order: “The law is like a telephone pole—you cannot jump over it, but you can always go around it.”

From the remnants of the USSR

The Soviet Union ran on a shadow economy. When it collapsed, institutionalised corruption and criminality metastasised. By 1994, Russia was home to over 500 criminal gangs controlling an estimated 40,000 businesses.

Come the early 2000s, the siloviki —Putin’s ex-KGB, military, and security loyalists—tightened their grip on the state. Analysts dubbed Putin's regime a “militocracy,” a government built by men in uniform. Meanwhile, the mafia wasn’t pushed out; it was folded in.

Organised, state-level crime has only grown since then. Russian universities now even embed sanction evasion into their curricula, the report says.

Moscow has weaponised its convicts in its war against Ukraine, trading prison sentences for front-line service. The “Russia’s Crime-Terror Nexus” highlights how the Kremlin is now recruiting criminals to conduct its dirty work across Europe.

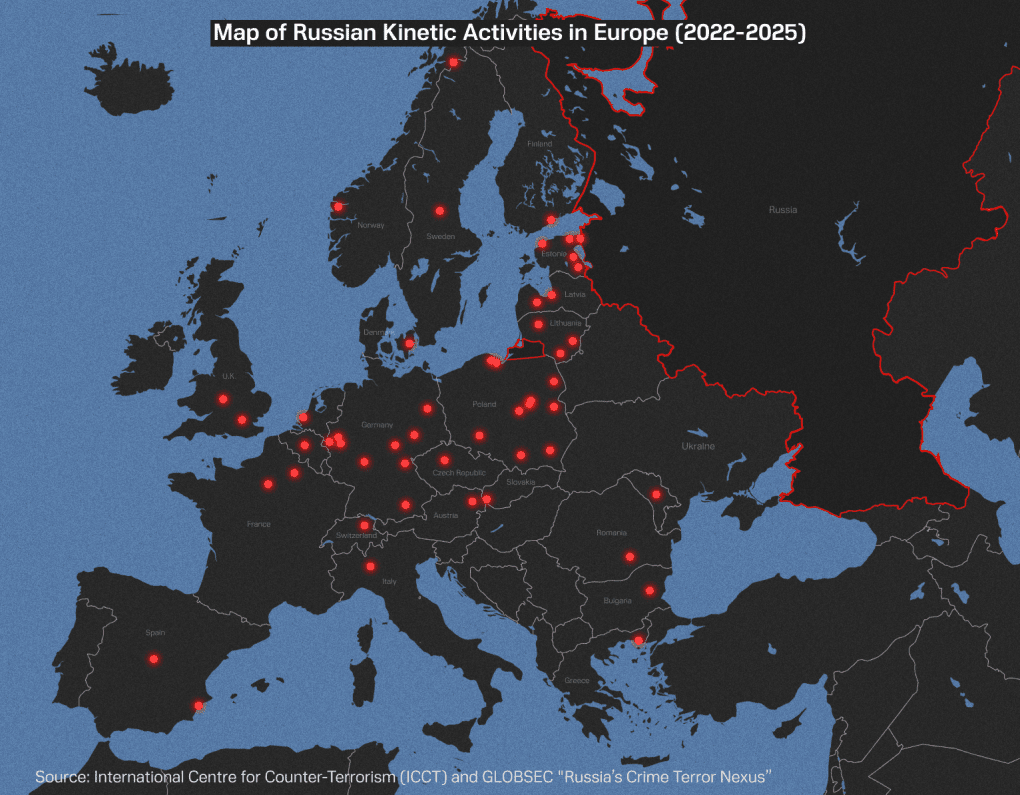

Mapping attacks on Europe

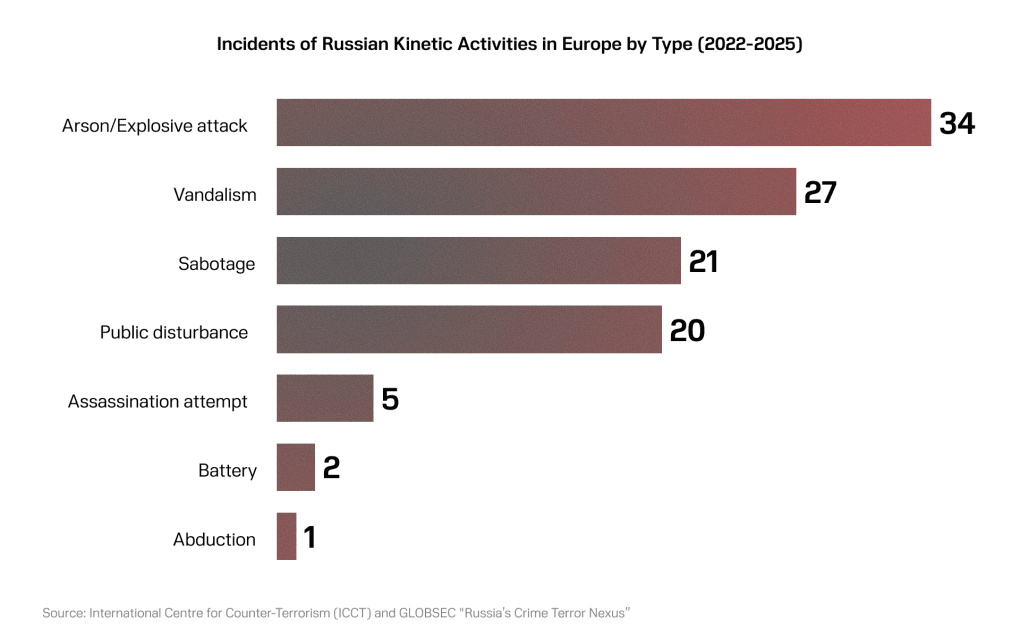

Between January 1, 2022, and July 31, 2025, 110 Russian-linked incidents were identified across Europe; 89 of these were successful, while 21 plots were foiled.

In a notable case, US and German intelligence agencies thwarted a Russian scheme to assassinate Armin Papperger, the CEO of Rheinmetall, a leading German defense company that supplies military equipment to Ukraine. The number of disrupted plots could be significantly higher due to intelligence operational security, the report said.

A quarter of the attacks were arson and explosive-related, followed by vandalism and sabotage. However, the attacks varied overall, including the assassination plot of the CEO of the German arms manufacturer Rheinmetall, the planting of incendiary devices on cargo planes, and the defacing of monuments.

The report found that nearly half of all incidents happened during the first half of 2024, revealing a sharp escalation after two years of waging war in Ukraine.

Poland tops the list—hit hardest with 20 incidents, both in scale and severity, since 2023. A critical supplier for military aid to Ukraine, it suffered nearly a third of all arson attacks. Targets included Warsaw’s biggest shopping centre, a major hardware chain, and sabotage attempts to blow up or derail trains carrying military aid to Ukraine.

France saw a wave of vandalism and street-level disruption mostly in the summer of 2024, coinciding with the Paris Olympics—right in line with reports of Kremlin plans to disrupt the games.

Germany’s strikes were graver still: two assassination attempts and five arson or explosive attacks.

The Baltic states—especially Estonia—became flashpoints of a different kind. Many incidents fixated on monuments to independence or the Soviet era, stoking friction between ethnic majorities and Russian-speaking minorities. Similar tactics surfaced in schemes to pit Latvians against Belarusian refugees. The region also faced high-profile hits, including an arson attack on an IKEA in Vilnius.

These operations served a dual purpose: disrupting public life and sowing fear, while also directly undermining Europe’s military support for Ukraine.

Russia’s Crime-Terror Nexus report

The attacks targeted both civilian infrastructure and military sites, such as ammunition manufacturers. The “Russia’s Crime-Terror Nexus” doesn't cover some of Russia’s other “greyzone” activities, such as drones in NATO airspace, or the sea cable sabotage in the Baltic Sea.

Who is behind the attacks?

Most recruits were men—93%, aged 16 to 59, with a striking share under 25, eight of them still minors. Women involved were often tied to partners already embedded in Kremlin operations. Kinship, friendships, and Moscow’s shadow networks played an outsized role in pulling people in, the report found.

-3fc44fab0e43e2670ac27762cecea3fb.png)

Hajdu says that Russia previously deployed a conventional approach by using its own operatives, as seen with the Skripal poisoning, but “since EU countries expelled over 600 of them since 2018, there are not that many left to conduct such missions.”

So Russia has turned to “outsourcing to outsiders—single criminals, socially or economically vulnerable individuals or organised crime groups—offers both manpower and plausible deniability. Organised crime groups are especially attractive, as they possess the criminal ‘know-how’ and networks”, Hajdu added.

The pool was a patchwork of nationalities—Russians, Estonians, Bulgarians, Ukrainians, Germans, Brits, and more. Many held dual passports; barely half lived in the countries where they carried out their attacks. As we’ve reported before, Kremlin-linked elites exploit second passports to sneak dirty money into Europe and bankroll the war—this same tactic greases recruitment.

The strategy is two-fold: outsourcing sabotage abroad makes it harder to trace back to Moscow, while economic hardship in Eastern Europe makes it easier to buy. Some Moldovans took jobs for as little as $58.

Money was the main motivator. Of 131 perpetrators, only 23 held pro-Kremlin views. Pay ranged from pocket change under $10 to more than $10,000. More than half knew exactly who they were working for.

A large share were criminals. Over a quarter had prior records—petty theft, drug trafficking, organised crime, even murder. Gangs often supplied the “foot soldiers,” offering Moscow layers of distance and plausible deniability—a method Russia has long perfected through propagandists, private military outfits, and now criminal networks.

Some cases read like crime thrillers: a dual Estonian–Russian smuggler, long working under FSB oversight, was tapped to spark sabotage inside Estonia. The arson of Latvia’s Independence Museum was coordinated from a Latvian prison cell.

Eight recruits had links to far-right extremist groups, particularly neo-Nazi circles. In three of those cases, far-right ideology meshed directly with pro-Kremlin goals. One German, previously a fighter in the so-called Donetsk People’s Republic, plotted to hit critical infrastructure and military sites.

Russia’s tactics are old tricks in new form—cheap, disposable agents backed by long-standing criminal networks. Once used for smuggling, they’re now probing Europe’s weak spots. The Kremlin won’t abandon tools that buy it deniability and manpower.

Instead, the report concludes, these operations are laying the groundwork for more serious campaigns during or pre-dating Russia’s next full-scale war.

-331a1b401e9a9c0419b8a2db83317979.png)

-46f6afa2f66d31ff3df8ea1a8f5524ec.jpg)

-206008aed5f329e86c52788e3e423f23.jpg)

-7ef8f82a1a797a37e68403f974215353.jpg)

-29a1a43aba23f9bb779a1ac8b98d2121.jpeg)

-554f0711f15a880af68b2550a739eee4.jpg)

-605be766de04ba3d21b67fb76a76786a.jpg)