- Category

- War in Ukraine

Poseidon, Burevestnik, Sarmat: Russia’s Nuclear Blackmail Under a Weakened Ruler

As Russia faces mounting military and political setbacks, Russian leader Vladimir Putin is increasingly leaning on nuclear threats—from “unlimited-range” missiles to doomsday torpedoes—to project strength that experts say the Kremlin can no longer guarantee.

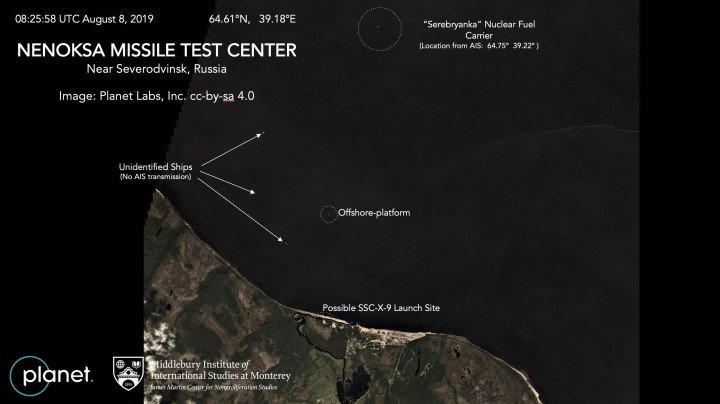

Five nuclear engineers and two Russian soldiers died inside a restricted zone in Nyonoksa, Northwest Russia, known as the State Central Navy Testing Range, during a failed experiment on August 8, 2019. The reason—an "isotope-fuel" engine blew up. Several people were hospitalized in Arkhangelsk with unusually high radiation levels, causing panic among medical staff. The accident occurred during tests of a nuclear-powered cruise missile called Burevestnik (NATO code name: Skyfall), triggering a small nuclear incident in the region.

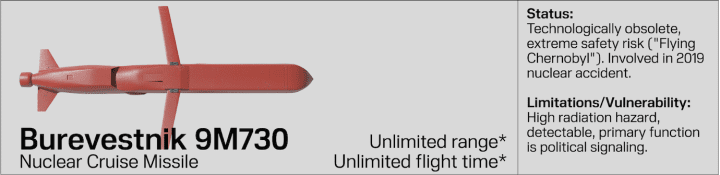

Russian leader Vladimir Putin has first promoted the Burevestnik as a missile with “unlimited range.” After this incident that the Kremlin tried to hide, it returned to the spotlight. Facing growing conventional weaknesses in its full-scale invasion of Ukraine, Russia increasingly leans on nuclear threats to discourage Ukraine’s partners from sustaining or expanding their support.

But does the Kremlin actually have the deterrence capabilities it claims? Is nuclear deterrence a real factor in resolving the Russian war in Ukraine—and what are the risks of escalating this rhetoric?

Russia’s large nuclear arsenal faces doubts about production, reliability, and safety

In 1994, under the Budapest Memorandum, Ukraine—then the world’s third-largest nuclear power—agreed to hand over the Soviet nuclear arsenal it inherited in exchange for security guarantees. Whether Russia would have invaded a nuclear-armed Ukraine is impossible to know, but the strategic imbalance created then is felt today.

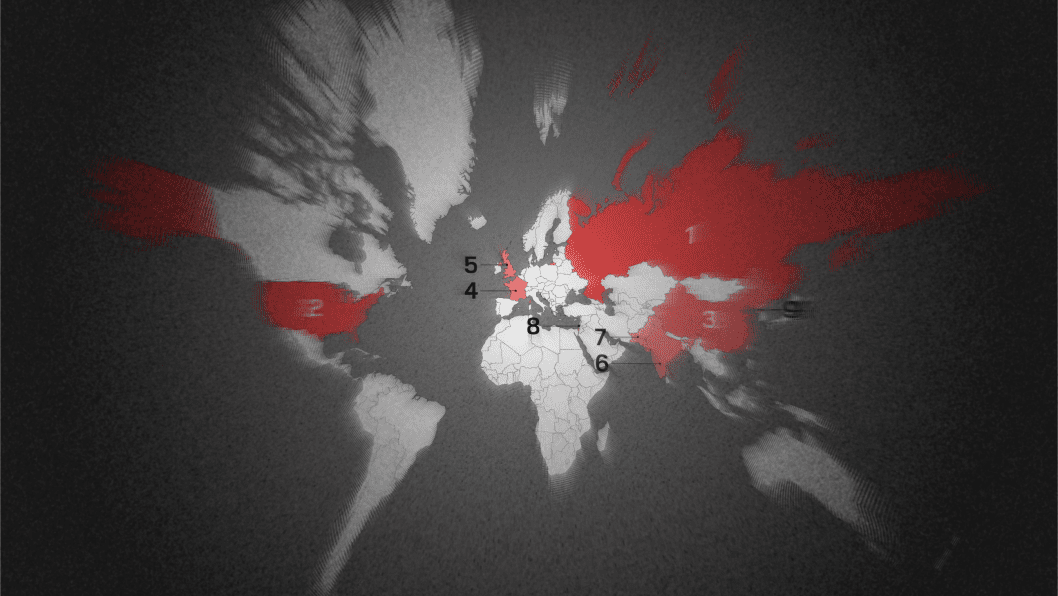

At the peak of the Cold War, the USSR held more than 40,000 strategic nuclear warheads. As of early 2025, the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, a top nuclear-security watchdog, estimated that Russia possesses 4,309 active strategic warheads out of a total inventory of 5,459, including around 1,700 deployed on land-based, sea-based, and air-launched systems. Russia and the United States together hold about 90% of the world’s nuclear warheads. But deterrence is not only about numbers.

Russia continues to highlight its nuclear role by developing new missile systems. Yet, this push for innovation often masks deep structural problems—limited production capacity, unreliable technologies, and significant environmental and safety risks.

We bring you stories from the ground. Your support keeps our team in the field.

Apart from legacy missile systems, like the R-36M/SS-18 “Satan”—a liquid-fuel ICBM introduced in the 1970s with a range of about 11,000 km, now poorly suited against modern missile defenses—Russia is trying to showcase new systems, reviving old Cold War projects.

Experimental and “next-generation” systems

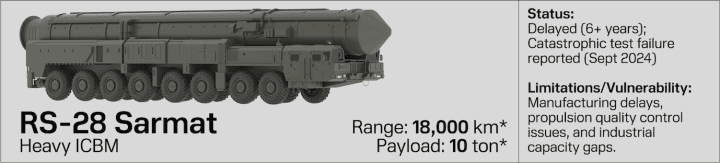

Sarmat

The RS-28 Sarmat (“Satan II”) is intended to replace the SS-18. Russia claims it can carry up to 10 tons of payload over 18,000 km and maneuver around missile defenses. Western assessments report repeated test failures and production difficulties. A test launch on September 24, 2024, resulted in a likely catastrophic failure, damaging the Plesetsk Cosmodrome launch silo. Deployment is now estimated to be at least six years behind schedule.

Avangard

Announced in 2018, the Avangard hypersonic glide vehicle was promoted as exceeding Mach 20. There is still no independent proof of its reliability or operational readiness. Analysts estimate Russia may have up to 18 units, but this remains unverifiable. Its development was reportedly delayed following Russia's 2014 invasion of Ukraine, as a critical control component was manufactured there, forcing a substitution program.

Oreshnik

The Oreshnik is an intermediate-range ballistic missile (IRBM), reportedly a variant of the RS-26 Rubezh, and is capable of releasing several small independent munitions near the target using a multiple independently targetable reentry vehicle (MIRV) payload, a configuration traditionally reserved for strategic nuclear weapons. The missile saw its first confirmed operational use on November 21, 2024, striking the city of Dnipro, Ukraine, but with empty warheads.

Belarus now hosts Oreshnik launch systems, giving Russia an additional platform for IRBM deployments close to NATO borders.

Burevestnik

The United States abandoned a similar program—Project Pluto—in 1964 due to extreme safety and environmental risks, including uncontrolled radioactive contamination. Western weapons experts described Russia’s nuclear-powered Burevestnik as outdated, detectable, and strategically pointless. Analysts cited by The Wall Street Journal and Deutsche Welle argue it is more propaganda than capability, with unstable propulsion and severe radiation hazards. The Nyonoksa accident in 2019 was confirmed by independent analysis, classifying the weapon as a severe, uncontrolled radiation hazard. Even if testing continues, production will likely remain extremely limited and will not change the strategic balance.

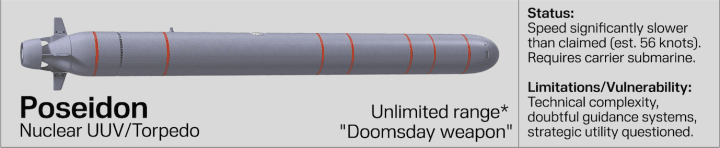

Poseidon

Russia launched the Khabarovsk on November 1, a nuclear submarine designed to carry the Poseidon nuclear-powered torpedo—often described as a “doomsday weapon”. Analysts note contradictions: if Poseidon truly had unlimited range, it would not need a carrier submarine at all. Western experts question its military purpose, citing unclear doctrine, technical complexity, and unreliable guidance systems. Initial claims that Poseidon could achieve speeds up to 195 knots using supercavitation are disputed; Pentagon estimates put its actual maximum speed closer to 56 knots. The weapon is designed to target US, UK, and French SSBNs or coastal cities.

9M729 cruise missile

Russia has used the 9M729—whose secret development pushed the US to leave the INF Treaty in 2019 due to its range violation—at least 23 land-based missiles against Ukraine since August 2024 (in addition to two launches in 2022). With a range of roughly 2,500 km (the INF treaty maximum is 500km), it can carry conventional or nuclear warheads. Debris found after recent strikes, including one on October 5 that killed four civilians, matched 9M729 components. The missile was confirmed to have flown over 1,200 kilometers to hit a target deep inside Ukrainian territory.

New nuclear-powered hypersonic missiles

Russia now claims it is developing a new generation of nuclear-powered cruise missiles capable of reaching Mach 3 and eventually hypersonic speeds. Experts warn that the technology remains risky and unreliable, citing past accidents such as the 2019 Nyonoksa explosion.

The nuclear deterrence today

Nuclear deterrence refers to the idea that the retaliatory power of nuclear weapons prevents states from launching a nuclear strike.

Carnegie Council

Although the Non-Proliferation Treaty remains under pressure, the post-1945 norm against nuclear use has held for 77 years. Ronald Reagan and Mikhail Gorbachev formalized this principle when they declared that “a nuclear war cannot be won and must never be fought.”, a statement that later paved the way for the INF Treaty signed by both countries in 1987. But the world has changed since the fall of the Soviet Union in 1991. “The overall complexity of military and political systems has grown, and with greater complexity comes a greater prospect of accidents,” says international relationships specialist Joseph Nye.

Russia has changed its nuclear doctrine in 2024, expanding the threshold for nuclear use to include conventional attacks that threaten the sovereignty or territorial integrity of Russia— and, that’s new, of Belarus—and not only when a conventional attack threatens the "very existence of the state," as stated by its latest 2020 doctrine.

Nevertheless, Benoît Pelopidas, founder of the Nuclear Knowledges program at Science Po (Paris), argues that nuclear weapons do not prevent war and can even encourage aggression. He cites numerous conflicts where nuclear powers or their allies fought despite nuclear arsenals : the Soviet blockade of Berlin (1948), North Korea’s attack on South Korea despite US nuclear forces (1950), the Yom Kippur War where Egypt and Syria attacked nuclear-armed Israel (1973), Vietnam’s war against nuclear China (1979) or more recently, Iran’s launch of direct missile strikes against Israel in June 2025 and Ukrainian military operation into Russian territory in 2024.

Russia’s nuclear rhetoric as a sign of weakness

Russia’s repeated nuclear rhetoric reflects what former Times diplomatic editor Michael Evans calls a “grave weakness and a failure.” Since the start of Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine, Russian officials—including Vladimir Putin, Foreign Affairs Minister Sergey Lavrov, and former Russian leader Dmitry Medvedev—have issued nuclear threats almost monthly.

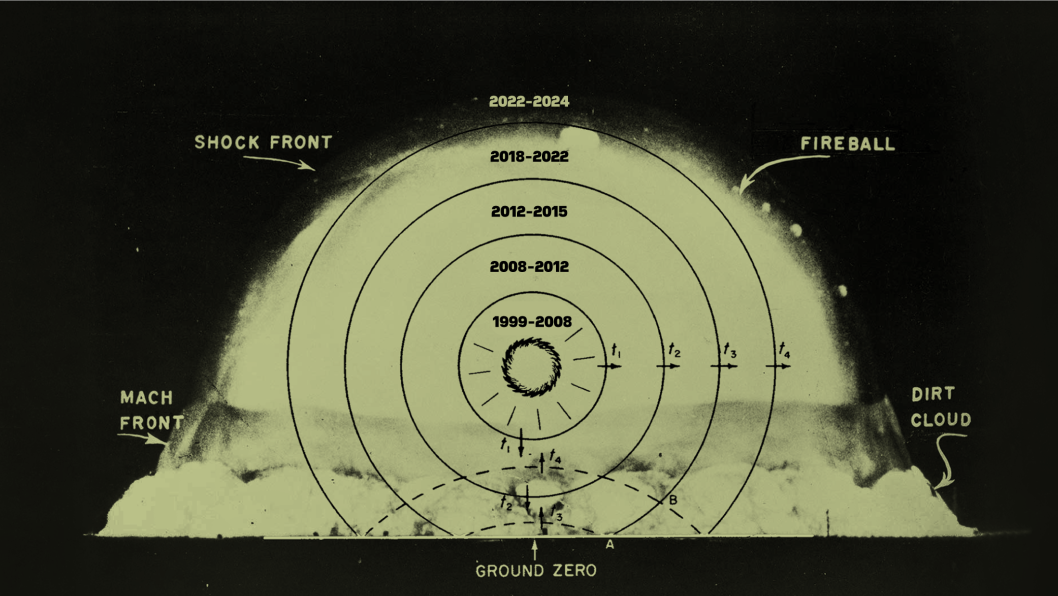

Russia repeatedly moves its “red lines,” issuing nuclear threats that it then ignores. These threats tend to intensify when Russia faces military setbacks or political pressure. The growing chaos inside Russia raises serious concerns. Putin is accelerating nuclear programs despite clear technical failures and deteriorating industrial capacity. The combination of weak governance, unsafe infrastructure, and reckless testing increases the likelihood of an accident—one that would likely occur in Russia first.

The recent escalation, including calls to restart nuclear testing, highlights this race to display ever-greater force—driven more by showmanship than by any real strategic thinking.

As Pelopidas notes, nuclear tests that change nothing militarily still harm the environment and heighten global risks. Climate change will also impact nuclear arsenals, particularly in terms of storage, cooling systems, and command-and-control resilience.

“The United States conducted more than 1,030 nuclear test explosions and Russia 715, the vast majority of which were to proof-test new warhead designs,” says Daryl G. Kimball, executive director of the Arms Control Association, “Neither side needs to or wants to develop a new warhead, so any new nuclear test explosions would be purely for 'show,' which would be extremely irresponsible.”

This article is not meant to defend nuclear deterrence or advocate for disarmament. The key point is that nuclear deterrence is a complex and high-risk system that depends on responsible decision-makers. The danger is less about Russia showcasing its nuclear forces and more about the fact that irresponsibility has become its defining feature—both toward the world and toward itself.

-8321e853b95979ae8ceee7f07e47d845.png)

-24deccd511006ba79cfc4d798c6c2ef5.jpeg)

-f88628fa403b11af0b72ec7b062ce954.jpeg)

-605be766de04ba3d21b67fb76a76786a.jpg)

-0c8b60607d90d50391d4ca580d823e18.png)

-29a1a43aba23f9bb779a1ac8b98d2121.jpeg)