- Category

- War in Ukraine

What If Russia Loses in Ukraine? Thinking the Next Security Order

After four years of large-scale fighting, Moscow has failed to achieve its military, political, or societal objectives in Ukraine. But even if Russia is defeated, the war won’t simply end. A deeper, harder question emerges: how do we prevent a weakened but militarized Russia from launching the next one?

For the classic of military strategy, Carl von Clausewitz, war operates on three levels: purpose (set by the government), means (executed by the military), and passion (the people, as the source of violence needed to achieve political aims). When applied to Russia’s war against Ukraine, the Kremlin has failed on all three.

Despite the Kremlin’s mounting list of unmet objectives and the erosion of its military and political capabilities, few in the international community seriously plan for Russia’s defeat. It’s not that the idea of Russia’s defeat is far-fetched—it’s that few have dared to map out what it would actually mean.

The core question is how to ensure that, once the guns fall silent, Russia is unable to attack again. What should be done after Russia loses its war?

We bring you stories from the ground. Your support keeps our team in the field.

“The first thing needed is to speak about ending the war on the most favorable terms for Ukraine,” Oleksii Melnyk, former officer in the Ukraine’s Air Forces and co-director of foreign relations and international security programs at the Razumkov Centre, says. “But victory must be seen as a process—one that begins after a ceasefire and the establishment of a lasting truce.”

Russia is not winning its war against Ukraine. In fact, this war is a failure for Moscow.

— Andrii Sybiha 🇺🇦 (@andrii_sybiha) February 4, 2026

In 2025, Russia lost 480,000 soldiers injured and killed while occupying an additional 0.7% of Ukrainian territory.

In January 2026, despite losing over a 1,000 soldiers per day on…

Is Europe ready for Russia’s defeat?

After suffering losses on a massive scale—exceeding US casualties during World War II, and which Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy has said amount to twice the Soviet losses over ten years of the war in Afghanistan in a single month of fighting in Ukraine—and achieving only limited results on the battlefield, Russia has revealed itself to the world as a colossus with feet of clay, echoing the biblical image from the Book of Daniel (2:31–35).

Russia, in Tver, the cemeteries for soldiers are being expanded again.

— Jürgen Nauditt 🇩🇪🇺🇦 (@jurgen_nauditt) January 17, 2026

All for the imperialist fantasies of a perverse dictator in Moscow.

The Avenue of Honor at the municipal cemetery in Dmitrov-Cherkasy has been expanded to four sections. A third and fourth section, located… pic.twitter.com/7kd69DyXRN

Russia’s military and strategic failure

Russia has yet to prove its efficiency, but battlefield facts go against its propaganda. Edward Carr, deputy director of The Economist, stressed that “the [Russian] offensive in summer 2025—his third and most ambitious—has been an abject failure.”

By contrast, Ukraine has transformed into “the largest military power in Europe,” said Melnyk, the “demilitarization” Russia sought has produced the opposite result.

Since 2022, Russia’s economy has rapidly shifted into a full war economy. The end of fighting would be unlikely to reverse this trend, given how difficult it has become for Russia to return to a prewar model.

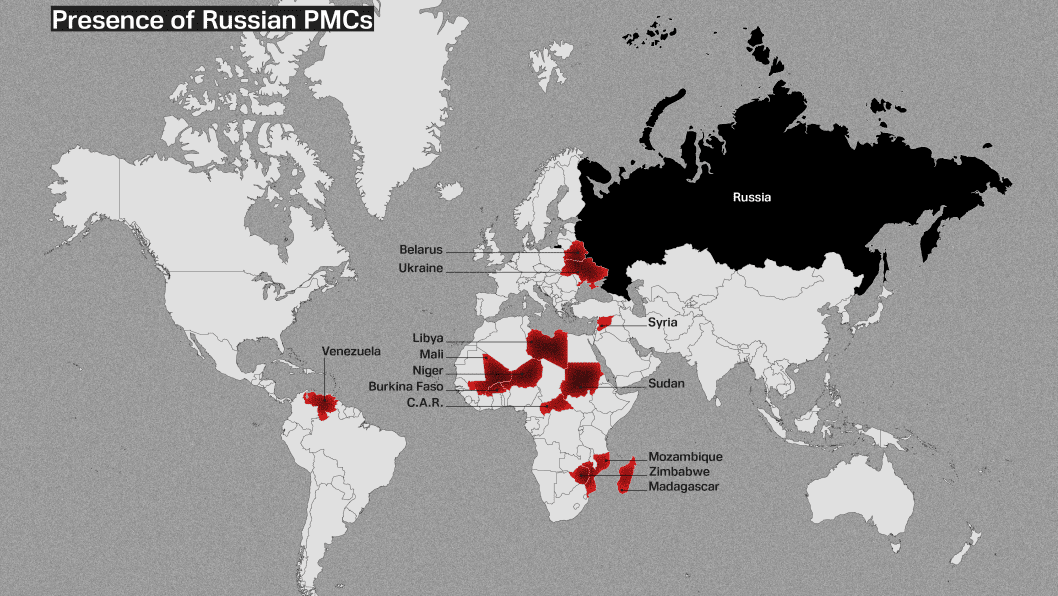

Unable to acknowledge defeat, the Kremlin may continue mobilizing the country at all costs—maintaining pressure on Ukraine or externalizing the threat to other fronts in hybrid or direct confrontations. Another scenario is the fragmentation of Russia’s armed forces into semi-autonomous formations, including private military companies (PMC), like “Wagner” or “Africa Corps”, a model that has already destabilized regions beyond Ukraine.

“War for Russia is already a modus operandi, it is their philosophy, it is a way of existence, a way of preserving the ruling regime,” said Melnyk.

This also represents a serious threat to Russia’s internal stability, one the Kremlin takes seriously. The return of hundreds of thousands of Russian soldiers to a country without a functioning veteran reintegration system—and to a society increasingly shaped by militarized values—could have severe consequences for domestic security and the stability of power. In 2023, Prigozhin's failed coup proved how the system can turn fragile.

Countering Russia with white gloves?

For reasons of territorial integrity and strategic defense alike, Ukraine will not abandon the territories Russia occupies—or may occupy—at the moment fighting stops.

“There will be no peace treaty,” said Yevhen Mahda, Ukraine’s Institute of World Policy director. “There could be a ceasefire, and it will be the beginning of a competition between Russia and Ukraine over who prepares faster for what comes next.”

Deterring Russia from launching another attack—and establishing a durable peace in Europe—therefore depends above all on deterring its willingness to attack.

Europe must understand that it cannot counter Russia with white gloves.

Yevhen Mahda

Director of the Ukraine’s Institute of World Policy

In a speech at Davos on January 22, 2026, Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy underlined European inaction, asking: “Why can President Trump stop tankers from the Shadow Fleet and seize oil—but Europe doesn’t?”

He also called for genuine European military coordination. “Europe needs united armed forces—forces that can truly defend Europe.” Russia, he argued, is already at war with Europe.

“De facto, the attack on Europe is already underway,” Melnyk said. “For now, it hasn't yet acquired such a kinetic dimension, but this is what the war against Ukraine started with.”

In its White Paper for European Defense “Readiness 30,” the EU states that “at the core of the readiness objective is ensuring that Europe has the full range of capabilities needed to deter aggression and defend its territory across all domains, including land, air and sea, cyber and outer space.”

However, it still does not explicitly name Russia as the threat—a hesitation that, according to Melnyk, reflects a regrettable delay in political resolve.

Will Putin wait until 2030, until Europe, roughly speaking, says, ‘Okay, now we are ready to meet you, your soldiers or your tanks’? That is quite a question.

Oleksii Melnyk

Co-director of foreign relations and international security programs at the Razumkov Centre

“Manageable threat”

For the US—the security umbrella over Europe since the end of World War II—the Russian threat has now fallen. In the 2026 National Defense Strategy released by the Pentagon, Russia is described as a “persistent but manageable threat” to NATO’s eastern flank rather than an acute or existential danger. Europe and Ukraine must therefore establish a long-term security framework in which dependence on the US is no longer essential.

Still unwilling to deploy troops to support Ukraine on the battlefield, European countries will have to continue—and likely increase—military assistance to Kyiv, while integrating Ukraine into a broader European defense structure outside NATO.

“Considering all potential alliances and coalitions, the Ukrainian army is currently the only one that knows—practically knows—how to fight Russia,” Melnyk said.

Mahda agrees. “Ukraine is the poorest country in Europe,” he noted, but it is also “Europe’s last knight.” Even without clear guarantees of EU or NATO membership, he said, Ukraine continues to defend Europe with “the most precious thing it has: the lives of its citizens.” However, he said that Ukraine must “rely primarily on itself” to survive and succeed.

Post-war economic shock

Russia’s losses in Ukraine are now translating into long-term economic constraints that will shape any post-war security order. The end of active combat would trigger what Melnyk describes as an “extraordinary shock” for the Russian economy.

After years of financing the war through reserves and energy revenues, the Kremlin has entered a phase of structural exhaustion: reserves are depleted, oil and gas income is under pressure, and the federal budget is increasingly sustained by high-cost domestic borrowing.

Can’t eat propaganda

Unable to mobilize at scale after the failures of 2022, and facing growing manpower shortages, financial incentives and propaganda have failed to compensate for the lack of popular motivation required to sustain a war on Ukraine and the World the Kremlin tries to portray as existential.

“You come here to kill people for money, that’s all,” a Russian officer told a soldier claiming to be a patriot, according to testimony relayed by a Bosnian mercenary captured by Ukrainian forces.

Russian society has already distanced itself from this war. In the overwhelming majority, people observe passively and hope it will end.

Oleksii Melnyk

Co-director of foreign relations and international security programs at the Razumkov Centre

Melnyk refers to the long-standing tension between propaganda and everyday reality—the struggle between the “television” and the “refrigerator.” While state media can sustain support for the war narrative for a time, the material consequences of prolonged militarization are likely to erode that support once economic pressure becomes impossible to ignore. Mahda, however, is less optimistic about the likelihood of social unrest and doubts that economic hardship alone will translate into political resistance.

The redirection of large segments of industry toward military needs, combined with sanctions targeting key sectors of the economy and financial system, has placed the country under constant strain. Labor shortages are worsening, while difficulties in extracting, refining, and exporting fuel continue to grow. According to Mahda, Russia’s economy is being kept afloat primarily through extremely high interest rates and the accelerated use of financial reserves—measures that are difficult to sustain over the long term.

The lack of alternative sources of financing [for the Russian military complexe], amplified by the steep drop in arms exports, makes the sector vulnerable to shocks to the oil price, tighter sanctions enforcement or a general recession.

Stockholm Institute of Transition Economics (SITE) at the Stockholm School of Economics

Wartime recovery

Ukraine, by contrast, has demonstrated both military and economic viability under wartime conditions, says Mahda. Despite ongoing attacks and infrastructure damage, the country has maintained industrial output, adapted supply chains, and preserved a functioning labor market. Ukraine’s workforce remains comparatively inexpensive, continues Mahda, while its industrial base has shown a capacity to survive under sustained pressure.

And international planning for Ukraine’s recovery is already underway. Politico reported that an 18-page draft “post-war prosperity plan,” circulated by the European Commission among EU member states, proposes a joint EU-US framework to mobilize up to $800 billion in public and private investment for Ukraine’s reconstruction and long-term economic development through 2040. The document outlines a ten-year strategy, including a 100-day launch phase, closer coordination with international financial institutions, and a stronger US role not only as a donor but as a strategic economic partner.

For Mahda, reconstruction should not wait for the formal end of hostilities. He argues that rebuilding must begin as soon as possible, starting with critical infrastructure, pointing to “communications, roads, and energy networks” as immediate priorities.

Ukraine is the largest reconstruction site in Europe. And those who begin investing now will gain a clear competitive advantage.

Yevhen Mahda

Director of the Ukraine’s Institute of World Policy

The question of reparations remains unresolved, but Melnyk points to frozen Russian assets as a potential source.

Whether through investment, reparations, or structural reform, the economic dimension of the post-war period will be decisive—not only for Ukraine’s recovery, but also for determining whether Russia can sustain its current model of permanent militarization and whether or not it can remain a threat to the world.

This means that restraining Russia after the fighting ends will not require new economic tools, but consistent enforcement of existing ones—tightening sanctions implementation, limiting access to technology and finance, and preventing the recovery of military-industrial capacity.

Nevertheless, a recent article by the Royal United Services Institute (RUSI) cautions against focusing solely on financial sanctions. As the authors note, “wars are rarely abandoned because they become expensive. They are more often terminated when states are defeated militarily, when ruling coalitions fracture, or when regimes themselves collapse.”

What happens to Russia after Putin falls?

If Russian leader Vladimir Putin loses, the system he built will face its most serious test, raising the question of what will happen to him once the war ends.

At the end of Ukraine conflict, we'll have a very big Russia problem

— Tymofiy Mylovanov (@Mylovanov) February 2, 2026

Russia will be reconstituting its force on NATO borders, led by the same people, convinced we're the adversary, and very angry. Putin taking on Baltic republics might be a gamble he's willing to take, Times 1/ pic.twitter.com/6p0rY2R0Lp

Regime change

But experts largely agree on one point: there is no realistic prospect of regime change in Russia imposed from outside. The scenario of a sudden collapse of the Russian state—or of the empire fragmenting—remains largely absent from Western diplomatic thinking. Melnyk says Western governments have even limited Ukraine’s counteroffensive capabilities out of concern that a decisive Russian defeat could destabilize Russia’s political system and lead to unpredictable geopolitical consequences.

“When I spoke about the reasons for the failure of the Ukrainian counteroffensive in 2023, one of the reasons was that the United States and European partners in no way wanted to see a convincing defeat of Putin,” Melnyk said.

Always remember. Not defeating Russia is a choice that Europeans and Americans are making. Nothing more, nothing less.

— Phillips P. OBrien (@PhillipsPOBrien) February 4, 2026

At the same time, Melnyk argues that focusing exclusively on Vladimir Putin risks missing the structural nature of the problem. “Putin is a problem in himself, of course, but it is not only Putin's problem,” he said. “It is the Russian security model: constant expansion, constant aggression, constant support of the narrative that they are surrounded by enemies. They need to fight, they need to seize zones of influence, create buffer zones.”

From this perspective, war is not an exception but a core mechanism of governance. It serves both external expansion and internal legitimacy, reinforcing the idea that Russia’s survival depends on permanent confrontation.

-468b36f05e43502a035bc3f202b7d61a.png)

Russian accountability after the war

A post-war security order will be unstable if it treats accountability as optional. Ukraine and its partners are already building a two-level legal architecture aimed at preventing Russia’s next war: a proposed Special Tribunal focused on the crime of aggression—the leadership decision to launch the invasion—and a much wider Ukrainian-led effort documenting war crimes and crimes against humanity across the temporary occupied and frontline regions.

This matters politically because it defines what “defeat” means beyond territory: not only military rollback, but legal responsibility that constrains future Russian leadership, delegitimizes the war narrative, and signals that aggression is not a reusable tool of statecraft.

But even if Vladimir Putin cannot be tried while still in power—“In the foreseeable perspective, this looks barely realistic”, says Melnyk—the accumulation of court-ready evidence, arrest warrants, and universal jurisdiction cases increases long-term pressure on the system around him—and reduces the chances of a fast “reset” that would allow Russia to rebuild influence without consequences.

The role of Russia’s opposition

Meanwhile, the Russian opposition in exile offers no clear alternative. It suffers from a lack of representativeness, unity, and coherence—particularly regarding Ukraine’s territorial integrity and Russia’s responsibility for war crimes. As Melnyk notes, it is also widely suspected of infiltration by Russian security services.

“[Russian opposition leaders] Navalnaya, Kara-Murza, Kasparov—with all due respect—are not representatives of the Russian people,” Melnyk said. “Aside from the fact that they differ little from those currently in power in Russia in their beliefs.”

The question of what happens inside Russia once fighting stops remains open. The return of large numbers of soldiers to a society shaped by years of war propaganda, economic strain, and repression could further strain the political system.

Empire as a system of governance

As historian Serhii Plokhy has observed, Russia’s war against Ukraine is not merely a regional conflict but part of a longer imperial trajectory. Empires rarely collapse in a single moment; more often, they erode over time through pressure, miscalculation, and recurring violence.

-588ae190d45987800620301cc34e2cf8.png)

In Russia, the question will arise: what was this all for?

Oleksii Melnyk

Co-director of foreign relations and international security programs at the Razumkov Centre

Melnyk argues that Russia’s reintegration into the international community without accountability “must not happen.” Such a move, he warned, would send a signal to future authoritarian leaders that aggression and crimes against humanity can go unpunished.

He also returns to the long-standing tension between propaganda and daily reality. “The propaganda there is powerful,” Melnyk said, “but it still has limits.”

Light at the end of the tunnel

Russia has not achieved its stated goals. It is retreating—or failing—across nearly every objective that justified the invasion. Its means have proven ineffective when measured against Ukraine’s capabilities. In practical terms, the Kremlin may lose the war it started, after expending enormous human, military, informational, and financial resources for no strategic gain.

Yet unless Russia ceases to exist as an aggressive empire, the end of large-scale fighting will not mean the end of the war. “As long as Russia remains within its current borders,” Melnyk said, “it will remain a constant threat. This is Russia’s security model: permanent expansion, permanent aggression.” The war is likely to continue in other forms. Ukraine and Europe must prepare for that reality.

“War is the continuation of politics by other means,” Carl von Clausewitz wrote in the early 19th century. Russia appears to have adopted a different position, one in which politics becomes the continuation of war by other means—a situation in which war has become indispensable to the survival of the Russian empire.

Ukraine must show that “there is light at the end of the tunnel,” Mahda said—by upholding the rule of law and acting in line with European values, without illusions about rapid EU or NATO membership.

“We proved in February 2022—when everyone thought we would fall—that Ukraine is viable,” he said.

To restore Ukraine’s territorial integrity, Mahda argued, Europe must address Russia as an aggressor empire and act accordingly.

Let's not forget that Russia illegally wrote the occupied Ukrainian territories into its Constitution... Therefore I say that in order to restore the territorial integrity of Ukraine, we must speak about the dismantling of Russia as an aggressor and influence this in the corresponding way.

Yevhen Mahda

Director of the Ukraine’s Institute of World Policy

Melnyk follows the same line: “There will be no end to this as long as Russia exists as an empire, or as an under-empire within the borders it currently has.”

As history shows, empire's expansionist nature remains a threat to those around it until it eventually collapses. “Then the iron, the clay, the bronze, the silver, and the gold were broken in pieces together,” reads the Book of Daniel. “And the wind carried them away, and not a trace of them was found.”

-7f54d6f9a1e9b10de9b3e7ee663a18d9.png)

-24deccd511006ba79cfc4d798c6c2ef5.jpeg)

-f88628fa403b11af0b72ec7b062ce954.jpeg)

-051a89e5a5304a3f0a58cfb1746eda24.png)

-605be766de04ba3d21b67fb76a76786a.jpg)

-206008aed5f329e86c52788e3e423f23.jpg)