- Category

- War in Ukraine

Ukraine’s Drone Revolution Is Forcing Europe to Rethink the Economics of War

When Russia launched its full-scale invasion in 2022, Ukraine was expected to be overwhelmed by Moscow’s far larger army. Instead, Kyiv responded with ingenuity, turning to drones and other improvised technologies to offset its disadvantages. Three and a half years later, these innovations have not only reshaped the battlefield in Ukraine but are forcing Europe to confront how quickly the economics of war are changing.

Europe is now grappling with the same cost dilemma that has haunted Ukraine for years: firing air defense missiles worth hundreds of thousands of dollars at drones that cost only a small fraction. In recent months, airports across the continent have been forced to shut down due to drone incursions, with European officials indicating that Moscow may be behind the disruptions. The economic impact of disrupting airports, trade routes, or other business activity with drones can escalate quickly.

Romania opted to track incoming Russian drones over its territory rather than waste missiles costing hundreds of thousands of dollars apiece, while the Geran drones they were intercepting were worth only a small fraction of that.

The Polish government believes Russia deliberately sent drones into its airspace last month to test NATO’s resolve and warned such probes will continue. Foreign Minister Radosław Sikorski said Poland needs a stronger counter-drone plan, noting that while allies scrambled jets and Patriots, those platforms are far too costly against cheap drones. “It is uneconomical and impractical to be defending our space with F-35s using Sidewinder missiles against drones,” he said.

Cost asymmetry of cheap drones

Cheap, long-range suicide drones can be mass-produced for a few tens of thousands of dollars and launched in waves that exhaust sophisticated air defenses built to stop million-dollar missiles. Russia’s use of Shahed variants in Ukraine has pushed Western governments and defense firms into an urgent race to build similar low-cost systems or affordable countermeasures, yet higher Western labor and material costs make rapid scaling difficult, according to a report by the Wall Street Journal.

The report also noted that last year, American company Anduril sold Taiwan 291 Altius long-range drones for more than $1 million apiece, including training and support, while Russia can produce Shahed-style attack drones for roughly $35,000 to $60,000 each.

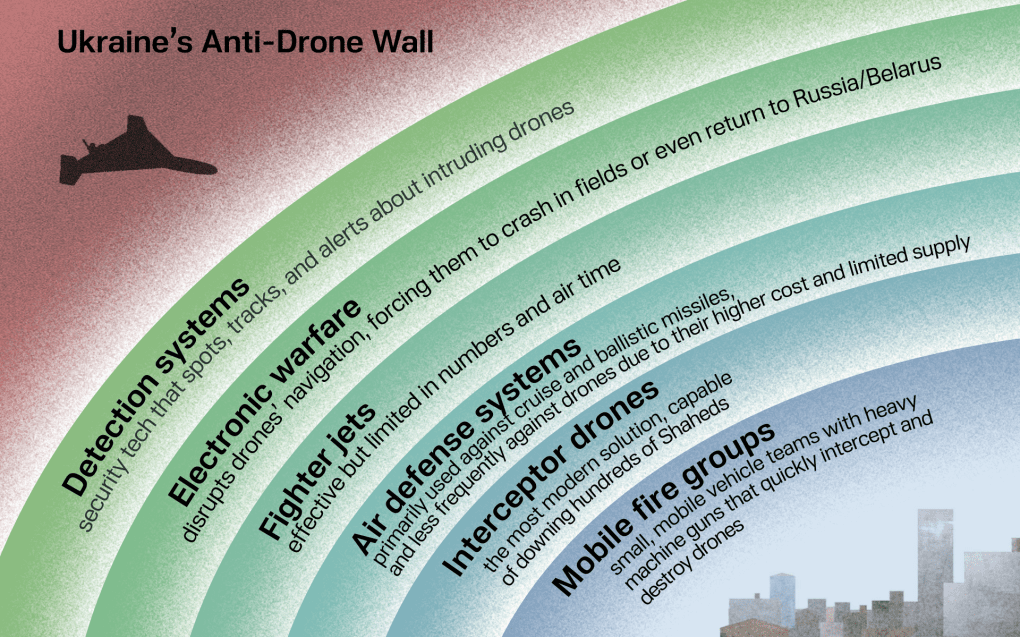

When Ukraine faced severe artillery shortages in late 2023, Kyiv turned to the mass adoption of FPV drones to blunt Russian advances. This innovation soon produced a “drone wall” that continues to inflict heavy casualties on Russian forces.

“Russia adapts with electronic warfare and new tactics, but each push through Ukraine’s defenses costs Moscow huge casualties,” said Serhii Kuzan, chairman of the Ukrainian Security and Cooperation Center and former Ministry of Defense adviser. “Despite this, Russia has failed to achieve any operational goals in its summer campaign.”

By 2025, drones accounted for 80% of Russia’s battlefield losses. Anatolii Tkachenko, commander of a mortar battery unit from Ukraine’s 92nd Separate Assault Brigade, stated that “in four years the USSR defeated Germany. In four years, the Russians have only managed to take half of Donetsk region.”

As Robert Brovdi, better known by his callsign “Magyar” and now commander of Ukraine's Unmanned Systems Forces, likened the drone wall to a wall “taller than the Great Wall of China.” Following a recent visit to a NATO base, Brovdi told allies in July that as few as four crews of Ukrainian drone pilots could have struck the site from 10 kilometers away. “I’m not saying this to scare anyone,” he said, “only to point out that these technologies are now so accessible and cheap.”

Among the starkest examples of cost asymmetry was Ukraine’s Operation Spiderweb, when teams used inexpensive drones hidden inside wooden trucks to strike Russian bomber bases deep behind the front, causing billions in damage. The same dynamic applies defensively as well as offensively. On October 10, a single $25,000 APKWS rocket intercepted a Russian Kh-69 cruise missile worth $500,000 per piece.

Drones transform warfare at land and sea

At sea, Ukraine’s naval drones have pushed the limits of what small, relatively low-cost platforms can do. The drones, which were equipped with missiles, not only disabled Russian ships but also shot down helicopters and fighter jets worth tens of millions of dollars each.

In May, Ukrainian Magura-7 naval drones, each worth about $300,000, reportedly shot down two Russian Su-30 Flanker multirole fighters valued at roughly $50 million apiece. The strike used AIM-9 Sidewinder infrared-guided air-to-air missiles, launched from the drones themselves.

General David Petraeus praised Ukraine’s ability to harness these innovations for asymmetric advantage: “The Ukrainian use of technology—particularly air and maritime drones, with ground robotic systems soon to follow—is sheer genius.”

Ukraine tends to be a little bit ahead in certain categories. This is a future in which a country with no navy created maritime and air drones that work together. They have sunk one-third of the Russian Black Sea Fleet and forced it to bottle itself up in a port as far from Ukraine as you can get in the eastern Black Sea, from which it doesn’t sail at all

United States Army general and former Director of the Central Intelligence Agency

“In the future, the cost asymmetry between cheap drones and expensive ships will mean that even a low success rate will prove highly damaging to naval forces, including Russia,” said Dmitry Gorenburg, a researcher with the Center for Naval Analyses. “The advantage of having a powerful navy will thus be somewhat decreased.”

Budanov: “The fleet is fully blocked. And that thing that Russians previously joked about, that Ukraine has no fleet — at least only a few boats — now they are faced with the same thing.” https://t.co/WmfLKNGYqG

— David Kirichenko (@DVKirichenko) June 12, 2025

Necessity drove innovation for Ukraine, especially when Western aid was being limited. “After Avdiivka, I think Ukraine really started ramping up drone production,” said Bohdan, a drone pilot from the Unmanned Systems Battalion of Ukraine’s 110th Separate Mechanized Brigade. “If Ukraine had more artillery back then, it wouldn’t have needed to rely as much on drones.”

Both aerial and ground drones have stepped in to fill gaps left by traditional weaponry, particularly artillery, said Deborah Fairlamb, a founding partner at Green Flag Ventures, a US fund investing in Ukrainian-founded companies. Their evolution is still in its early stages, she said, but predicted they would remain central to Ukraine’s defense, playing crucial roles on both offense and defense.

Far from the front

But Ukraine’s innovations have not been confined to the front line. As Russia pounded Ukrainian cities with waves of drones and missiles—and the previous Biden administration restricted Kyiv’s access to Western long-range weapons—Ukraine began building its own fleet of long-range drone bombers. These systems now serve as a form of “kinetic sanctions,” striking oil refineries and fuel depots deep inside Russia, triggering shortages across the country.

Russia’s vast geography, once considered its greatest asset, has become a vulnerability as swarms of Ukrainian drones overwhelm its air defenses. To open corridors for the bombers, Ukraine often sends in decoys, forcing Russian air defenses to waste precious missile interceptors before the real strike arrives.

Russia is showing signs of severe strain in its air defenses, following Ukraine’s ongoing drone offensive. Professional Buk missile crews have been reassigned to the infantry because there are too few surface-to-air missiles left to fire, in some cases, only one or two for every six vehicles, according to Russian “milblogger” Maxim Kalashnikov. The shortage highlights a broader reality Moscow can no longer ignore as cheap drones are quickly outpacing costly air defenses.

Asked whether necessity drives innovation, a deputy commander in the 63rd Separate Mechanized Brigade’s Unmanned Systems Battalion, who uses the callsign “Babay,” said Ukraine’s rise as a drone power was born of survival. “It’s not because we’re so smart—it’s because we’re poor,” he said. “We make ‘poor man’s solutions’ from wood, Chinese parts, whatever works. That’s how FPV drones evolved, too. Two years ago, small projects grew into large ones. Now we can hit targets 100 km away. I’d say we’re still at only 25–30% of our UAV [Unmanned Aerial Vehicle] potential.”

Research and development are constantly required by frontline units. “In our unit alone, we have four workshops—for repeaters, airborne repeaters, explosives, and modifying drones to use multiple frequencies,” Babay said. “With cash, we can adapt in days. With government procurement, by the time the order arrives, the need has already changed.”

Driving battlefield innovation

Throughout 2025, Ukraine’s BRAVE1 initiative has worked to bridge the gap between rapid frontline demand and slower traditional procurement. While the Ministry of Defense’s new decentralized system has been dubbed an “Amazon for weaponry,” BRAVE1 complements it by linking commanders with domestic startups and manufacturers, turning battlefield problems into prototypes within weeks and ensuring innovations can be refined and scaled at speed.

That cycle of battlefield trial and adaptation has compressed dramatically. Ukrainian drone pilots also earn points for destroying Russian military targets, with certain ones, like enemy drone pilots, having higher rewards. They are then able to use those points to purchase equipment that is needed.

In the first year of the war, new battlefield technologies held up for about seven months before being replaced. By 2023, the cycle had shrunk to five or six months, in 2024 just three to four, and by early 2025, it was around four to six weeks. “This war is about breakthrough solutions and using technologies in a system of systems, and the side that leverages this better and faster has the advantage,” said Samuel Bendett, an adjunct senior fellow at the Center for a New American Security.

The race to scale

Ukraine’s next leap is scale. Defense Minister Denys Shmyhal recently said the country aims to deploy up to 1,000 interceptor drones a day, a target that underscores both the scale of Russia’s nightly attacks and Kyiv’s determination to meet them with mass rather than expense.

“We test, validate, and then push the state to scale up proven solutions. We also connect different military units so they can share knowledge directly,” said Lyuba Shipovich, CEO of Dignitas Ukraine. “Volunteers move faster than the government.”

Civilian-led groups like Dignitas Ukraine are now complementing state efforts with low-cost, layered defenses. Its FreedomSky initiative is building a distributed anti-Shahed frontier, a scalable network of interceptors, communications, and power systems that shows how volunteer innovation can also fill gaps in traditional air defenses at minimal cost. "The first priority for the military is the front, while these volunteers can stay in cities and protect territory within,” said Shipovich.

Volunteers may move faster than the state, but speed alone is not enough. As Vitaliy Goncharuk, the former chairman of Ukraine’s Artificial Intelligence Committee, cautions: “Innovation is not the decisive factor. It matters over a one-to-three year horizon, but it’s not an end in itself—because innovative solutions cannot be scaled in just a few months.”

He argues that the real competition lies in scaling, “the ability to mass-produce a very limited set of innovations that deliver a systematic advantage.” But the challenge is that the longer Russia can wage its war, the more time it has to learn from its mistakes.

Russia can now mass-produce hundreds of drones a day across multiple types: inexpensive decoys that cost $2,000–$10,000 each and larger Shahed-style systems with 60 kg warheads priced at $30,000–$60,000, according to Heiner Philipp, an engineer with Technology United for Ukraine. That mass presents a strategic problem—and an economic one—for defenders.

“The solution must be proportionate,” said Philipp. “If you shoot down $10,000 decoys with $2–5 million missiles, you’re losing the war. You must make the attack technically a failure and economically a failure.”

Ukrainian frontline units have adapted a layered, low-cost defense: mobile teams using machine guns, interceptor drones, and, as a last resort, missiles. Radar and acoustic networks track incoming UAVs along the front, and gunners with thermal sights can engage cheap drones at little cost per round.

In an October Fox News interview, Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy said that Ukraine’s interceptor drones have destroyed 68% of Russian Shaheds, calling them the most cost-effective defense, costing $3,000–$5,000 each compared to $120,000–$150,000 per Shahed.

The Financial Times likewise reported that Ukraine’s Sting interceptor, produced by the Wild Hornets company, costs about $2,100 compared to more than $1 million for an AIM-9X missile used in NASAMS batteries. This new generation of drone busters combines speed and affordability, reaching 315 km/h and detonating on impact, with Ukrainian activist Serhii Sternenko claiming a 70 percent hit rate.

Philipp noted that some interceptor drones cost between $1,000 and $2,000, can reach speeds of up to 400 km/h with small payloads, and are guided by local radar teams.

Roy Gardiner, an open-source weapons researcher, says Ukraine’s edge lies in speed. The country’s new interceptor drones can reach about 300 km/h, fast enough to chase down most Russian UAVs. By contrast, FPV drones work well against reconnaissance targets but are too slow to catch Shaheds cruising near 200 km/h.

“Field reports put kill ratios between roughly 30–70 percent depending on unit and conditions,” said Philipp. These interceptors are now in demand across Europe as governments scramble to prepare for the same challenge, following Russian drone incursions into Europe. “Western countries are just beginning to grasp this,” Fairlamb said. Several European nations are now working to build their own “drone wall,” modeled on Ukraine’s experience.

Indeed, any orders placed with Ukrainian manufacturers help them scale production and reinvest in research and development. “Providing funding for orders from its defense industry will have an immediate impact. Ukraine’s defense industry will be massive as well,” said Branislav Slantchev, a political science professor at UC San Diego.

On October 16, US firm AIRO Group and Ukraine’s Bullet signed a letter of intent to form a 50/50 joint venture to produce a fixed-wing interceptor capable of speeds around 450 km/h and ranges near 200 km. The agreement aims to move combat-tested Ukrainian designs into Western production lines, creating a certified counter-drone option for US, NATO, and Ukrainian customers, while potentially supplying Europe’s emerging “drone wall” with fast, industrialized interceptors.

Yet in this technological duel, every move prompts a countermove. Months of devastating Russian air attacks have shown that Moscow is also adapting its missiles. Western and Ukrainian officials told the Financial Times that Russia has upgraded its Iskander and Kinzhal ballistic missiles to perform last-second maneuvers that “confuse and evade” Patriot interceptors, sharply reducing Ukraine’s interception rate.

“The Russians are now using combined strikes to catch our air defenses off guard. So tactics and technologies are evolving constantly,” said Mykola Melnyk, a former Ukrainian officer from the 47th Mechanized Brigade. Russia has been deploying countermeasures against those drone interceptors, as it has supercam drones with radio detectors that sense approaching interceptors and trigger automatic evasive maneuvers.

“The future lies in mobile fire groups, units equipped simultaneously with machine guns, MANPADS, and interceptor drones,” he said. “Coordinated with air force units, such teams could make it nearly impossible for enemy drones to get through.”

The war has become a grinding tech contest of adaptation, with each side racing to out-innovate the other. For Ukraine, the challenge is not simply inventing the next breakthrough but scaling a cost-effective solution fast enough to offset Russia’s mass. For Moscow, the lesson is equally clear as it struggles to keep pace with swarms of cheap drones across its vast territory.

-331a1b401e9a9c0419b8a2db83317979.png)

-e704648019363ef9514cdd89b9bacc91.jpg)

-605be766de04ba3d21b67fb76a76786a.jpg)

-0c8b60607d90d50391d4ca580d823e18.png)

-29a1a43aba23f9bb779a1ac8b98d2121.jpeg)

-76b16b6d272a6f7d3b727a383b070de7.jpg)